The Political and The Politicized: Deterritorialization in Canadian Poetry

Before I state what this review is, I will state what it isn’t. I’m not one to take the podium and make statements about what is and isn’t political; I’m not even here to say what is and isn’t poetry. After all, when it comes to the ecology of writing, “Poetry” is more a description of the shelf on which certain writing is sold, rather than any kind of inherent structural description. I have neither the expertise nor the experience to interfere with the large and varied language of poetics and its politics, but I’d like to think I have read enough poetry to begin speaking on what poetry can do to the political.

Many caveats first need to be addressed. Throughout the past few years, critical reviews and negative reviews have become arbitrarily synonymous. I agree with the simple fact that there exists a lack of critical approaches to book reviewing in Canadian literature; however, I diverge from the loudest voices of such narratives which seem to be those of exclusively older, cis-white male critics who have integrated both a great deal of pettiness as well as an arbitrary culture of scarcity into reviews of Canadian literature from a diverse set of backgrounds that they have no expertise in.

I’m going to start this review by saying: There are many aspects of the works I am engaging with that are not to my liking, but every word in this review comes from a place of love and respect.

The persistent current culture of Canada’s “critical reviews” has ensured that IBPOC reviewers remain in the periphery, since any “critical” approach they undertake towards the writing of other IBPOC is later co-opted by white supremacist spectators and hate groups to further destroy the reputations of other IBPOC. Such “critical reviews” are therefore scarcely written BY IBPOC, FOR IBPOC, and ON IBPOC writers, which creates a vacuum where there exists no space to critically engage with works that one may not completely agree with.

I’m going to start this review by saying: There are many aspects of the works I am engaging with that are not to my liking, but every word in this review comes from a place of love and respect.

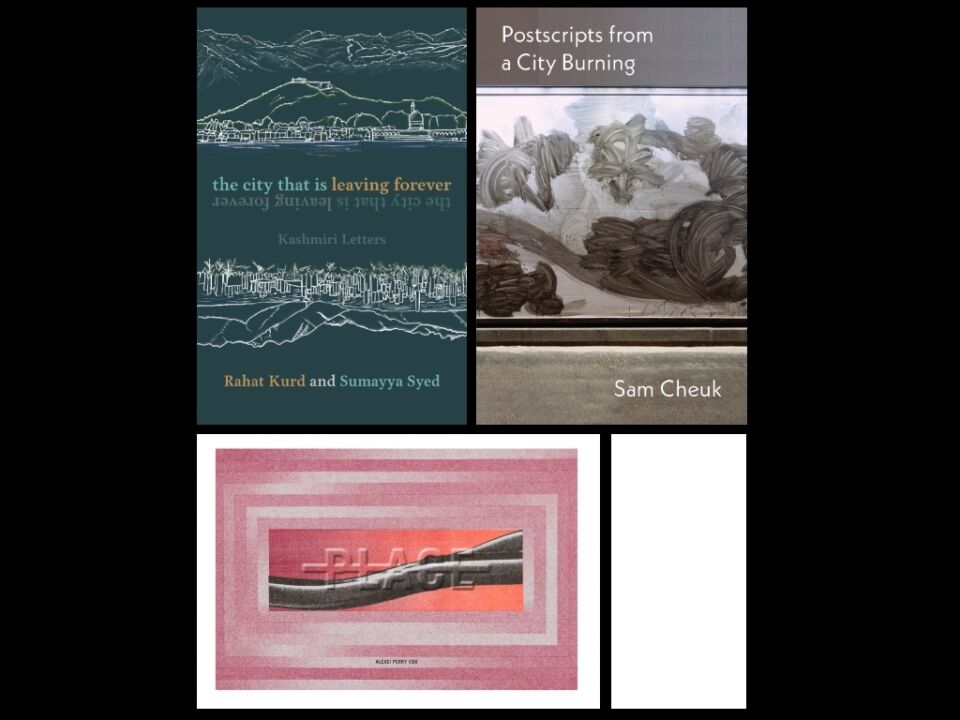

It is hard to gauge a writer’s political intent through their poetry, the same way that it is hard to guess a driver’s destination by the brand of their car. The books Postscripts from a City Burning, PLACE and the city that is leaving forever: Kashmiri Letters have very divergent approaches to identity politics and politics in general, based on their degree of political conveyance as well as their cultural vantage points.

Sam Cheuk’s Postscripts from a City Burning is a diary of poems composed while protesting on the streets of Hong Kong in 2019-2020. The poetics of the political is awakened in not only the poet but the entirety of the city with the book’s heart-wrenching opening lines: "A mood descends on a city/ call it fidelity maybe./ but it is not love. neither can its name/ be mercy.” The poems sound immediate because they actually are. They are written daily, on the streets, amidst violence and death. They start with the sunrise; they end with sundown. No poem spans longer than a day. Here Cheuk writes from within the incident, situated in the city of Hong-Kong, in 24-hour news cycles. The poems are composed from the inside and projected towards an unknown future.

In the poem dated 11/07/19 we read “Your face, turning away. / suggests otherwise. /There is no shame in wanting/ To be more beautiful.” However, this very “romance” with the inner spirit of revolt creates a peepshow for anyone peeking from outside of the incident, and the ethics of what this “out group” of political observers do with these poems is beyond Cheuk’s power.

When it comes to politics, one must first examine poetry as a means to deliver politics, as well as examining politics as a means to produce poetry. There’s the age-old question of poetry as a luxury. The periphery of poetry is filled with people who claim there is no power to be wielded within poetry at all, and I’m not here to answer that question, but here to ask sub-questions considering a certain given: lets say we consider poetry as truly crucial to disturbing power imbalance and its production to be fully in tune with political praxis. The major question then becomes “Is the politicization of poetry inherent or circumstantial?”

When asking such questions I must for the first time address intent. When faced with any poetry labeled “political” let us ask: “in this piece, does the poetry precede the politics? or is the converse true?” That important question is there to explore whether the politics was a means or an end.

When reading Cheuk’s book, I can’t help but ask myself, “Is the poetry speaking or listening?” The audience is perhaps inconsequential to both the intent and the extent of the poems; maybe the work is simply an emotional narrative of the individual, divorced from any spatial and temporal belonging; that perhaps when concerned with the emotional weight of the poem, the setting and the period of time are entirely arbitrary. Do not however mistake the arbitrary relationship of the poetry to its emotional narrative to be in any way representative of an arbitrary relationship with territory, temporality and space. Perhaps Postscripts from a City Burning was meant to be a daily diary of Cheuk’s 2019-2020 either way, in Hong Kong or not. Perhaps all Cheuk wanted to do was listen; first to a crumbling city, and then to us, beyond the page. Perhaps Cheuk was writing, and his writing was further politicized. Let’s ask ourselves a question: let us go over and replace all utterances of “Hong Kong” with “Seattle” or “Manchester”. Would it still be political? Or is the poetry political due to an inherent birthright?

Cheuk’s work is intimate and beautiful. Postscripts of a City Burning romanticizes the very essence of rebellion, how a people’s revolution, once set into motion, can be stopped by near to nothing. If we consider Cheuk’s work a “document” of the struggle, due to its explicitly descriptive approach to Hong Kong’s protests, however, the work does not interrupt the power imbalance. In the real world of the protest, the power lies with the government, violently crushing a people’s rebellion; in the poems, that power persists, since the format of the poems lends itself to further lacerating, further wounding the already wounded, time and time again. In a poem dated 11/16/19 we read “they announce their names,/ yelling “I will not kill myself”/ while being dragged away,/ in case their name is mistaken/ for one fallen by mistake.” Cheuk’s work seems to be stuck in its narrative of oppression—this is neither an affront to the writing nor to the writer, since not everyone is capable of escaping it. “Documenting” trauma, however, is perhaps a way in which no political power is subverted within the poem. Where a poem can subvert power is through the implicit, through formal abstraction, through what poetry does best: an utter dismantling of the “logos.” If the real world is absurdly cruel, so should be the poem.

While Cheuk writes Postscripts from a City Burning as perhaps a lament, Kurd and Syed write the city that is leaving forever: Kashmiri letters while consistently wrestling for control. Just as Cheuk situated his book within tumultuous Hong Kong of 2019-2020, Kurd and Syed likewise situate their book of poetry and hybrid letters/correspondence within a Kashmir that has been struggling for decades. Here the city that is leaving forever diverges from Cheuk’s work, since where Cheuk seemed to be trapped within the narrative, floundering to escape but seemingly unable to (of no fault of his own), Syed and Kurd are merely situated within the spatiality of catastrophe, and in fact, the turmoil itself hardly even breaks into the narrative.

There is something deeply meditative about the city that is leaving forever. The writing is slow and methodical, one that makes you stop at the corner of every sentence to smell the roses. But this very smelling of roses is psychologically interesting. Syed and Kurd have never had the privilege of leaving Kashmir behind for a very simple reason: the wound has never healed for it to pass the temporality of “violence” into “trauma.” Cheuk was deeply attached to the “Space” of Hong Kong while Syed and Kurd are deeply attached to the temporalities of Kashmir; from the deeply ancestral to bakeries that closed a few years ago.

Trauma is a term that makes sense only in retrospect: there is no trauma without an end to the violence in the first place. This can be seen in writings from within the most tumultuous war-torn countries: the Hasan Blasim of War-torn Iraq does not write of the bombings as an “incident” or an “event” that have now passed and are reflected on; no! they are ongoing events which simply decorate the real content: the banal narrative of everyday life itself. The Israeli occupation is not central to Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry; not any more than the trees he lives among. In the same way, the turmoil in Kashmir isn’t the subject, but the "Space" that Kurd and Syed simply traverse to live their daily lives. Just like Cheuk, their writing is immediate, because nothing spans more than a day. Most of the book is simple correspondence, sometimes several messages in a day, discussing food, weather, family. Two women, whose daily troubles with children and communities are undermined whether in the depths of catastrophe or not. Let’s repeat the exercise we did with Postscripts from a City Burning. If we go through a city that is leaving forever to change every utterance of “Srinagar” with “Paris” or “Milan,” will it still be political? Or are Syed and Kurd, like Cheuk, simply politicized by birthright.

Kurd and Syed have been living within never ending grief (though Kurd does not currently live in Kashmir), and therefore no longer mention much about spectacular oppression of war and government lockdown, but instead explore the oppressions they face that are given less airtime on the news. They speak about simple things within the domicile because that’s what their life is: the simple problems they face daily while the city slowly packs up to “leave forever.” They showcase severe longing, both for what once was and a nostalgia for what never was. In an entry dated 2018-05-30 Syed writes: “the truth is that I want to leave, not just travel./ But to leave and never have to return” and Kurd responds “I know that exact “never”/ almost too intimately”.

The 'poetry' of their correspondence, the gentle explorations of domestic life, memories, poetry and languages is a poetics that precedes the political.

The question of the Audience simply resolves itself in the city that is leaving forever. Kurd and Syed are simply speaking to each other, and courteously allowing anyone interested to stand by and listen. That’s perhaps the most delightful advantage of a correspondence, that by anticipating an immediate audience, a correspondence strives for more clarity and legibility. For Syed and Kurd, it once again begins to feel like this series of poems, letters, correspondences, would have happened either way, whether interrupted by Kashmir’s struggles or not. (I understand that discussing the “Poetics” of the city that is leaving forever is perhaps pushing the concept of “poetry” and “Poetics” a bit, since the majority of the book isn’t poetry. Lets consider the “poetry” of Kurd and Syed’s work in a wider, less defined sense.) The “poetry” of their correspondence, the gentle explorations of domestic life, memories, poetry and languages is a poetics that precedes the political. Though severely politicized and pre-political, Kurd and Syed are very deeply situated within their environments.

Now we get to the most challenging book of the bunch: Alexei Perry Cox’s PLACE. When it comes to conceptual poetry I have always been rather incapable of connecting the dots, and there are a lot of dots to connect in PLACE. I’ve always enjoyed works of literature in conversation with something outside of itself; however, there’s a limit to the amount of conversation you can include in a book and still speak to your audience clearly.

I have read Perry Cox’s PLACE a total of five times, and it is a testament to its titular aversion of states. But that’s where I begin to worry for the state of the political in the work: The very naming of the book PLACE seems to be a plight for deterritorialization.

Where Cheuk practiced a somewhat compatriotic romanticism of revolution and rebellion, Perry Cox approaches the book with a radical plight for all writing that is political, no matter its genesis or shortcomings (something that becomes doubly apparent when we see a quotation from Mao Tse-Tung). Unlike Cheuk, Kurd and Syed, Perry Cox ferociously self-proclaims their own writing to be political, as well as wishing emancipation for all in the notes section. Perry Cox is the only writer so far that has set out to achieve a political goal from the beginning.

Having read Perry Cox’s previous works, PLACE is their least personal book, in a purely literal sense. There is almost no mention of “I”; no self is present, just explorations, transliterations, translations and elaborations on revolutionary text and speech. Here the word “Revolutionary” is simply exploring all language that exists within a revolutionary framework, it is once again de-ontologized.

The book features a total of 7 languages, all of which Perry Cox is fluent in. Several chapters explore languages other than English; from translations and elaborations on revolutionary thinking and writing, to a chapter where a third of the text is Chinese thought written in Chinese characters. The book seems to be exploring rebellion in terms of revolutionary language itself, using space as a container where speech and writing take place. In this way, though the writing is deeply rooted in Language, which itself is ethnically, temporally and spatially developed, the discourse grows increasingly deterritorialized. It almost feels like Perry Cox is proposing a radical dissolution of space from political poetry itself, and rooting political thought in language alone (meaning Language in a general and Derridean sense).

Alexei Perry Cox is more politically informed and poetically trained than I, but my argument here isn’t that their efforts are misinformed. I am simply positing that Perry Cox’s initial intention may have been widely different from the “average" reader's experience (i.e. yours truly). If the book had focused on a single cultural milieu (i.e., just the Chinese thought, just the pan-Arabic, or just the Indigenous knowledge), It could have avoided becoming diluted by unifying wildly convergent political milieus in a single book. PLACE suffers from over-quoting, an act that can dilute accountability as well as direct political attention before speaking; however the quotes act in vastly different manners. Sometimes they frame the thoughtspace of a chapter (i.e., quoting Rinaldo Walcott on liberty when speaking of, well, liberty) and other times, they are used as a window through which we can look at history (i.e., quoting Mao to recontextualize).

It seems that Perry Cox wants to put forth the idea that what matters is that we share a language for revolt. However, though Perry Cox is IBPOC themself, this simple line of inquiry proves problematic to IBPOC over the long run. For IBPOC, identity politics and the discourse around racial injustice are emphatically specific to a certain ethnicity, language, religion, state and sexuality. Cheuk, Kurd and Syed are longing for something lost within their crumbling cities and their corresponding communities, are reaching for control; however, I’m unsure what Perry Cox is striving for in PLACE, since their political language is neither entirely devoid of signification to be universal nor specific enough to be site-specific. In the end I have trouble placing Perry Cox within any of the political situations clearly, but one thing is for sure. Perry Cox has started at politics and arrived at poetry.

It’s an important question to pose before writing any poem really, not only a political one.

Some writers write poetry, and are situated within the political by circumstance like Kurd, Syed and Cheuk. Others are inherently political, no matter what they write, and poetry is simply the tool with which they deliver their politics. What becomes clear in this path is simply where poetry serves, and when it is of disservice to the political questions at hand. Instead of making a statement, I’d like to once again pose a question: what does the format of poetry serve to the political? We all know that poetry has its shortcomings in interacting with the general populace, from low percentage of readership to low legibility for those with little interest in the medium. I’m a lover of poetry and have always been, but more often than not, I arrive at political poetry thinking “Could this have served its purpose if only it was written in another format, like nonfiction or essay?” and it’s an important question to pose before writing any poem really, not only a political one.