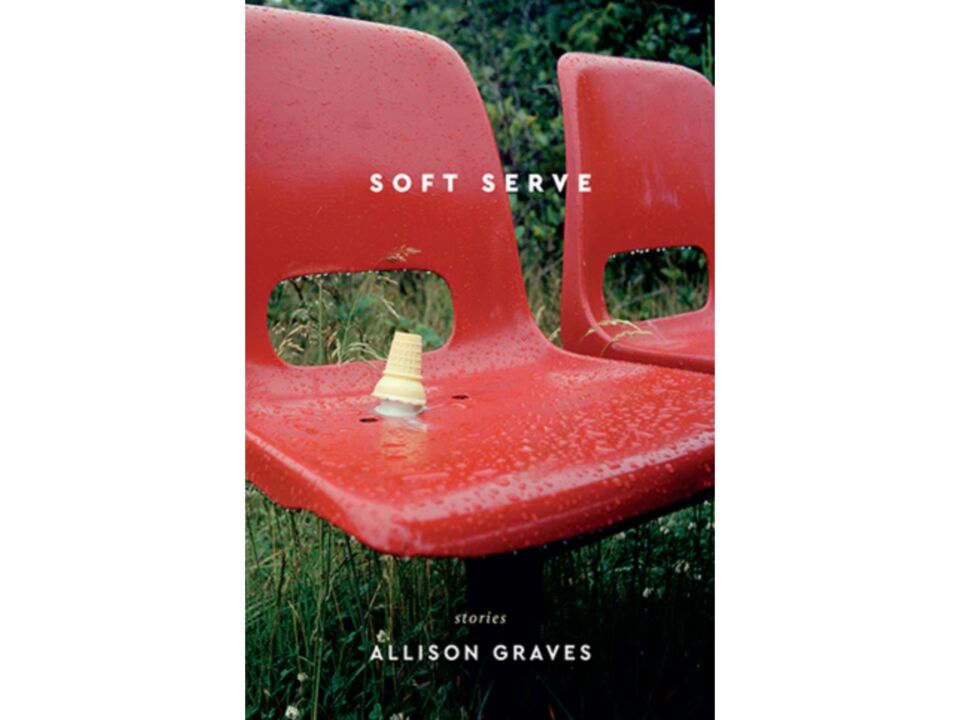

Funny and Tragic: A Review of Soft Serve by Allison Graves

St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador-based author Allison Graves’s first short story collection, Soft Serve, feels like one Canadian coming-of-age story that has been divided amongst a menu of characters. Graves presents characters across 19 stories who often find themselves on the brink of self-realization—the brink, it turns out, is located anywhere between a used car lot in Guelph, a snowbank in St. John’s, Montreal’s Mile End, and an Eaton Centre. The back of the book informs readers that Graves considers people in the “non-places of modern life,” though I suggest they stand out most against the backdrop of consumerism and big business as quintessential places of their time. Central to the crowd are millennials who find meaning at a Boston Pizza, sign divorce papers at Yorkdale Mall, fall in love in an Ikea showroom, and have their first sexual experiences on top of Toronto Maple Leafs sheets. Graves’s exploration of the middle-class, millennial experience is inextricable from her portrayal of the corporate menagerie; often positioned in the midst of consumer markets, the stagnancy of her characters becomes a form of resistance to their fast-paced environments.

In her careful juxtaposition of humour and tragedy, consumerism and the consumer, and disillusionment and hope, Graves’s form mirrors her most radical suggestion: that growing up is learning to sift through the ordinary to recognize that which is profound.

Rather than simply overwrite the individual as yet another byproduct of modern times, Graves questions the relationships her characters have with one another and their settings through an expert combination of irony and sincerity. In “Staying Alive,” eighteen-year-old Olivia goes for fast food with her father as he prepares to tell her about his prostate cancer diagnosis. The news is laughably mundane within a suddenly mystical McDonald’s parking lot where the two stand “under the golden arches—her father bathed in yellow light.” Graves plays with the intersections of banal events and true milestones by treating both with a mixture of apathy and wit. “A drop of gravy [falls] on the page, right over the words irreconcilable differences” as two characters finalize their divorce at the Yorkdale Mall in “Standby.” In “It’s Getting Dark Out,” the shocking election of Trump as President of the United States rivals the news that Lucy has broken up with Mitch. As funny as the comparison seems, it also roots Lucy’s life firmly in relation to the politics around her, just as the spilled gravy is granted more importance than the signatures on divorce papers. Frustrated by her father’s positive reaction to the election results, Lucy comes to realize, “I’m just tired of trying to understand people.” Just a few pages later, we find a complete differentiation between the before and after of this political event: “The past felt so much easier than any future she could imagine.” In her careful juxtaposition of humour and tragedy, consumerism and the consumer, and disillusionment and hope, Graves’s form mirrors her most radical suggestion: that growing up is learning to sift through the ordinary to recognize that which is profound.

“Value” stands out as a successful criticism of pretty privilege and the cost of assigning worth to beauty standards, a cyclical theme in Soft Serve.

In “Value,” this comes across while Graves considers the cost of middle-class privileges through a misunderstanding at a used car lot. Amber’s dad asks about the price of a car using Newfoundland slang, “What’s she worth?” to which the salesman replies, “how much is who worth?” Amber’s world becomes reminiscent of the car lot as she realizes that everything around her is assigned value. Her milieu is described through a contrast between working class adults and privileged high schoolers: “Wedged between the twenty-four-hour factory workers and the cross-country truck drivers were a bunch of rich kids partying.” Erin—one of the rich kids—wears $200 jeans and was able to afford cosmetic surgery for an overbite that resulted in subsequent weight loss. For being “pretty in a normal way,” Erin comes home with $500 worth of clothes from American Apparel and the company’s promise of a $1,000 photoshoot. All of this is a reward for Erin losing so much weight that Amber can clearly feel her spine during a congratulatory hug, an observation that causes concern for Erin’s health. “Value” stands out as a successful criticism of pretty privilege and the cost of assigning worth to beauty standards, a cyclical theme in Soft Serve.

One aspect I struggle with lies in the recurring tension within Graves’s depiction of female relationships. While jealousy and resentment are considered classic to the coming-of-age trope, these feelings seem inherent to Graves’s female characters. In “Value,” Amber is only “mostly happy for Erin, that people were finally noticing that she was beautiful.” In “Eat Me,” when Miranda’s girlfriend is invited to exhibit at MoMA, Miranda is “jealous in this like really primal way.” In “Standby,” which revolves around the introduction of polyamory to Kathleen’s marriage to Arthur, Kathleen remembers the failure of her friend Darcy’s marriage as a passing comfort: “When Darcy got divorced it made her feel better, which she didn’t say, she just assured Darcy she was better off.” I do not take issue with the presence of competition between women, rather that this is a common motif that Graves continually references while leaving largely unexplored; both “Eat Me” and “My Friend, My Parrot” vocalize these feelings, but don't go much further. The otherwise peripheral presence of female jealousy dilutes the impact of more forward-thinking feminist commentary scattered throughout the stories.

Graves’s writing is at its best when she considers the nostalgic echoes of the past as part of a millennial’s vision of the future.

Graves’s writing is at its best when she considers the nostalgic echoes of the past as part of a millennial’s vision of the future. Her characters bask in the memory of Blockbuster’s relevance and pre-Covid-era snowstorms; the collection is framed as much by the passing of time as it is rooted in the span of the millennial experience. She coins the “fraudulence of memory” and tells one character through the voice of his date that all creativity is ephemeral: “Dude, just paint something” she writes, “It’s fine, it’s not going to be there forever.” In “Staying Alive,” Olivia recognizes the generational gaps between her vision for the future and that of her family members. While she is not unconcerned by the passing of time, she believes she can hold on to some parts of her present: “Her parents and Daniel were existing in a world where everything was fleeting and whoever could hold on to life the longest would win. But Olivia was looking to hold onto something different, something meaningful. She really believed that people could love the wrong thing and still be okay.” Rather than expand on Olivia’s beliefs or work against her parents’ cynicism, Graves leaves readers to decide what constitutes wisdom versus naïveté. In the titular story, “Soft Serve,” the generational gap is at its most defined and wide as we bear witness to the desperation of an older man and the bewilderment of his daughter and grandson in the wake of his apparent suicide attempt. Much like the larger collection as a whole, the multiple perspectives highlighted in “Soft Serve” saturate the story with familiar tensions—nihilism and hope, loneliness and abundance, consumption and satisfaction—as the characters struggle to differentiate between the ordinary and the profound, the “funny or tragic.”