Between War and Identity

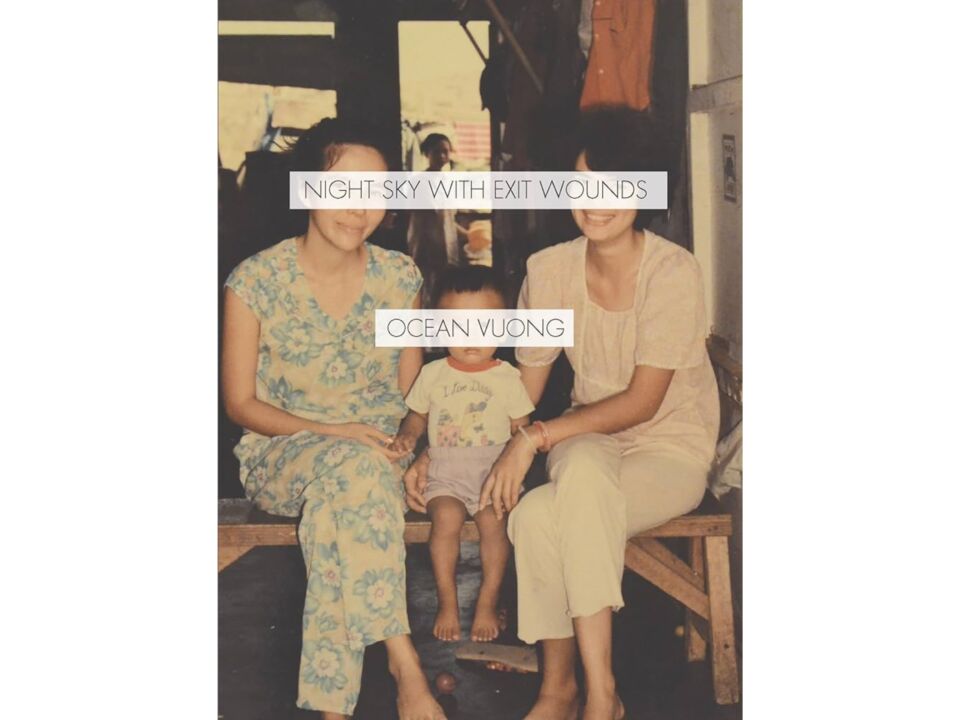

Vuong’s first poetry book, Night Sky with Exit Wounds, tackles the burning weight of dragging an endless war with him everywhere he goes. Though the work has an overarching theme of war, every page smelling of fresh gunpowder, he also writes about his queerness, family relationships, and disconnect from his Vietnamese identity. Vuong’s distinct stature as a poet has gained popularity in recent years, especially due to the publication of his debut novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (which, by the way, is probably the most well-crafted piece of prose I’ve ever read). He’s received notable prizes for the aforementioned, Time is a Mother, and more. His poem “Self-Portrait as Exit Wounds” (partly included further down in the review) was awarded the Pushcart Prize. I wanted to focus on his earliest work to highlight the foundation of many of the themes he is known for today. Often, his verses come banging and end swiftly, leaving the reader with the feeling of having something handed to them, to it just as suddenly being taken away just as quickly.

It’s the bomb saying here is your father.

Now here is your father inside

your lungs. Look how lighter

the earth is—afterward.

To even write father

is to carve a portion of the day

out of a bomb-bright page.

There’s enough light to drown in

but never enough to enter the bones & stay.

Using the imagery of the bomb crashing directly into the reader’s mind, the reader is presented with an interesting imagery in order to instill a fraction of Vuong’s lived experience.

Dedicated to his parents, the book is a collection of cultural grief, estrangement tangled with nostalgia, and daringly shocking war imagery that evokes the feeling of astonishment. The shocking character of many of his poems is contrasted by the saccharine words of some of his other pieces included in the work. “Even my name / knelt down inside me, asking / to be spared,” is a spine-chilling example of how heritage and memory of home are doused in tragedy and the inability to go back. In fact, this meagre existence inside himself is what he opens the collection with: “In the body, where everything has a price, / I was a beggar. On my knees.”

Vuong’s speaker grapples with the bittersweetness he feels toward his war-torn country. He writes:

... a city trying to forget

the bones beneath its sidewalks, then through

the refugee camp sick with smoke and half-sung

hymns ...

At the same time, the words are woven in a meticulously humble manner, transmitting how utterly empty he feels or felt. “For in the body, where everything has a price, / I was alive.” The sheer vulnerability in his work makes you treat every syllable with care as to not crush them. It’s the extreme contrast between the violence and ruckus of his country of origin and the heartbreaking yet subtle surrender of his every defence that makes this book so compelling. He is not afraid to politicize his work, either, often depicting brutal scenes of American soldiers ravaging his homeland. Perhaps the most explicit and bone-chilling is the example below from his poem “Self-Portrait as Exit Wounds”:

... the sky replaced

with fire, the sky only the dead

look up to, may it reach the grandfather fucking

the pregnant farmgirl in the back of his army jeep,

his blond hair flickering in napalm-blasted wind, let it pin

him down to dust where his future daughters rise,

fingers blistered with salt & Agent Orange ...

Vuong also includes descriptions of the war in overly simplistic ways, perhaps to highlight the straightforward quality of many atrocities committed against the Vietnamese. By removing any baroque language and metaphor, he manages to dryly deliver how devastating a simply-described act can be. “An American soldier fucked a Vietnamese farmgirl. Thus my mother / exists. / Thus I exist. Thus no bombs = no family = no me.” Its description leaves the reader with the raw emotion of bittersweetness toward the war. To this extent, the speaker seems determined to convey how, had the war never happened, he wouldn’t have been born, thus shedding light on more of the reasons why the war is a great cause of internal turmoil for him. In this way, something that from the outside seemingly absolute is approached from a more nuanced, inside perspective. Vuong’s complicated circumstances as a Vietnamese-American permeate the fibres of the collection. While his experiences reveal some of the horrors of the Vietnam War, they also speak of the clash that is generated from living in a country that is responsible for both the tangible and intangible damage he and his family have had to endure.

Vuong writes about queerness from a very introspective and intimate perspective, often including, in great detail, his experiences as a gay man. The speaker is not afraid of describing deeply intimate moments within his life in his work, creating a sense of closeness with the reader as well as contrasting the terror of war and the temporary comfort and safety of human relationships.

& sometimes

your hand

is all you have

to hold

yourself to this

world

It’s with this metaphor of the body that he pushes further the narrative of a nationless young man who has been robbed of a home and thus struggles to know where he belongs.

The above is an excerpt from his poem titled “Ode to Masturbation,” which describes with great vivaciousness the intimacy and knowledge of one’s own body and the delirious need to hold onto something that can be called one’s own. It’s with this metaphor of the body that he pushes further the narrative of a nationless young man who has been robbed of a home and thus struggles to know where he belongs. While very telling of his war-related struggles with home, the poem also speaks of a much less metaphorical relationship with his sexuality. It talks not only about his body, but also others,’ depicting them in a feverish yet literal matter, combining extravagant language with a tinge of vulgarity, as in his description of “the cumshot / an art / -iculation” and complemented by verses such as:

you

who twist

through barbed

—wired light

despite knowing

how color beckons

decapitation

In other instances, he also uses very direct language to describe sexual interactions, such as when he writes “another man leaving / into my throat.” The convergence of such seemingly different ways of expressing the same thing is beautiful and bizarre and Vuong captures it masterfully. His mentions of his queer identity are sometimes followed by moments of doubt, such as when he wrote “I met a man. I promise to stop.” Though he has pieces such as the above that mix description styles, Vuong has written others that highlight the intimacy of his relationships without the explicit elements. This is something I particularly appreciated because it shows the less than linear relationship someone can have with a part of themselves—or between multiple parts, for that matter. Vuong makes sure to never take anything for granted in his work and, in a way, that transmits the feeling of always being on your feet, never fully aware of what the next verse might bring.

I waited

for the night to wane

into decades—before reaching

for his hands.

Another important piece of this collection is the sky mentioned in the title. It’s implied that it’s the sky he’s trying to exit or escape, serving as a symbol of the inescapable quality of the war he grew up with and its residue, which makes its way into his everyday life in the form of distressing memories. “They say the sky is blue / but I know it’s black seen through too much distance.” The exit wounds also mentioned in the title may be referring to bullet wounds, much in the way they are presented here:

the bullets pass

right through you

thinking

they have found

the sky as you reach

down

The image of skin being the sky creates a very human comparison of the tangible with the intangible, and perhaps even the divine. It is perhaps the word “divinity” that describes Vuong’s poetry style best, given his transcendental but raw way of describing his experiences and observations.

in his quiet praying—

as some will do before raising

their weapons closer

to the sky.

Once again, Vuong makes mentions of weapons or ammunition whilst talking about the sky, further pushing the relationship he draws between violence and gunfire and an omnipresent, inescapable force. This is perhaps alluding to his feelings of helplessness regarding his memories of the Vietnam War. The sky is everywhere, after all, and there’s no use trying to hide somewhere if it’ll follow you.

His descriptions of nature aren’t reserved to the sky, though. However, unlike those of the sky, he writes about them as an ode to the beauty of his country and his life before they were stripped from him due to war.

To lift

this snout, carved

from centuries of hunger, toward the next

low peach bruising

in the season’s clutch

The above is a gentle yet vivid retelling of a sweet, dewy memory of home. However, not every instance of these descriptions is simply beautiful. Its lull is sometimes also mixed with sudden, ephemeral instances of juxtaposed elements of terror that stand out from the description:

it’s june

until morning you’re young until a pop song

plays in a dead kid’s room water spilling in

from every corner of summer & you want

to tell him it’s okay that the night is also a grave

we climb out of

In the excerpt above, the words “dead kid” pop out from the rest of the verses, allowing for an open interpretation from the reader of what that could possibly mean amidst the rest of an otherwise colourful description.

In his poem “Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong,” he writes as if in a letter to his former (future?) self—drawing connections between his body and about the war: two recurring and connected themes in this book. “( ... ) The most beautiful part of your body / is where it’s headed” and “the most beautiful part / of your body is wherever / your mother’s shadow falls." Both start the same way, the anaphora acting as a reminder to himself about where to put his body or what to do with it. In the same poem, and much more grotesquely, he describes the longing to feel safe and at home in himself: “I swear, you will wake— / & mistake these walls / for skin.”

Lastly, he mentions his family extensively throughout the work, specifically his mother and grandmother, but his father as well. He says: “Like any good son, I pull my father out / of the water, drag him by his hair.” His feelings toward them are expressed as somewhat contradicting, especially toward his mother, though there seems to be an underlying thread of appreciation for them all, despite their many faults. “But only a mother can walk / with the weight / of a second beating heart.” is juxtaposed with the following verses:

A mother’s love

neglects pride

the way fire

neglects the cries

of what it burns.

He contrasts the tireless effort mothers put in to nourish their children while also mentioning them as a burning fire. Later in the work, he makes his feelings toward his mother very clear: “6:57 a.m. I love you, mom.” This phrase was written amongst other excerpts from his notebook, which supposedly means it was compiled as yet another disorganized and sudden thought, contributing to its authenticity.

At its core Night Sky with Exit Wounds is a coherent and wonderful piece of work that grapples with the lifelong trauma of being born in a war-ravaged country and having to leave as a result of it. It offers lots of powerful insight on Vuong’s personal life and it conveys the experience of many other Vietnamese-Americans who are living a similar reality, where the country they turned to for safety is simultaneously a home and a hostile reminder of their old life’s destruction. The bittersweetness he feels toward his own life and body permeate his every word and through his poems he creates a truly immersive experience into his tumultuous life. Universal themes of internal conflict, depression, queerness, and war can be understood by a wide range of people, whether in a more literal or metaphorical way.