“Thinking outside the coffin”: An Interview with Dr. Dorisa Costello about the good, the bad, and the endlessly transformative creatures of the night

Dr. Dorisa Costello has a long history with vampires, both personally and professionally. Her doctoral thesis combined critical and creative perspectives to examine fragmentation and non-linear narrative, Victorian prosopopoeic poetry, identity, and mental and physical illness.

Dr. Dorisa Costello has a long history with vampires, both personally and professionally. Her doctoral thesis combined critical and creative perspectives to examine fragmentation and non-linear narrative, Victorian prosopopoeic poetry, identity, and mental and physical illness. Although the work lacked any mention of the cult-favourites Dracula or Nosferatu, one of its subjects, the Victorian poet Algernon Charles Swinburn, identified the Greek poet Sappho as a pseudo-vampire in his poem, “Anactoria.” After successfully confronting every aspect of academic life on one side of the lectern, she did what any of us would do…returned to the other side of academia and taught various humanities subjects in the US, Macedonia, and Lithuania. Today, she teaches academic writing, English literature, and English stylistics at Vilnius University and English literature at William Jessup University. Her most recent academic publication is the article “Female Vampires as Embodied Critiques of Heteronormativity, Blood-mixing, and Patriarchy: From Carmilla to Fledgling” (2019), which explores the intersections of race, gender, and the body in vampire novels. At some mysterious point of the day, most likely between midnight and the witching hour, she continues to work on her latest project—a long-form analysis of the female vampire in literature and visual media as both a vehicle for social anxieties and also for overturning power dynamics. The analysis is intended to examine a wide variety of female vampires, including Carmilla, Shori, Bella Swan, Selene, Marceline, and possibly a few others. As perhaps subtly alluded to by the preceding series of facts, Dr. Costello’s areas of interest include British Victorianism, Gothic literature, gender and sexuality studies, media studies, and speculative fiction. Often, this assortment is embellished—and thus made more approachable—by a pop-culture reference, a geeky analogy, or an example sentence involving Buffy.

I am a former student of Dr. Costello, current freelance writer, and perpetual language learner. I have yet to conduct an in-depth academic analysis of the vampire archetype of my own. However, I recognize its appeal, adaptability, and impressive ability to endure within the collective consciousness. As a typical language and literature enthusiast, I’ve familiarized myself with the depictions of Dracula, Upyr, and Nosferatu in their original languages. Overall, there is a much bigger amalgamation of other works and anecdotes based on just how gracefully classic Hollywood and Gaumont horror effects tend to age throughout the years that led to this interview. Alas, that is a topic for another day. Some of my non-vampire-related texts can be found on various Lithuanian news media sites (in Lithuanian), on the website of the Spanish arts and culture magazine METAL (in English), and soon in the online version of the Belorussian culture magazine Bolshoi (in Russian).

From Vlad to Vladislav, from Dracula to Chocula and far beyond, vampires boast perhaps one of the richest and most enduring mythologies amongst a wide variety of cult horror characters. We chat with English and Creative Writing Ph.D. Candidate and Vilnius University lecturer Dr. Dorisa Costello about the complicated history, unused potential, and uncertain future of the immortal—or at least the infinitely adaptable—vampire. This conversation has been edited for clarity.

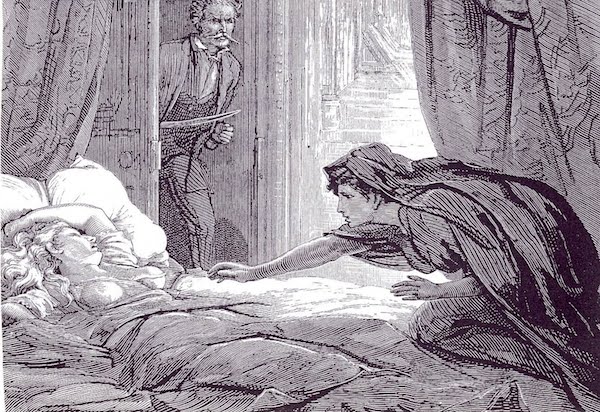

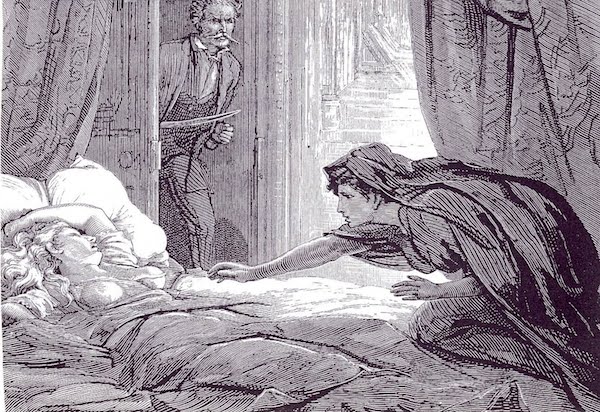

Julija Kalvelytė: What, if any, stages or crucial works can be identified throughout the evolution and modernization of the classic vampire? How did we get from Stoker’s Vlad to Clement’s Vladislav? Dorisa Costello: First, I have to admit my limitations here, in that I’m only familiar with English-language texts, so there may be major works that I am neglecting. But in terms of the development of the vampire in English-language literature and media, vampires began as oral folklore co-opted as religious, anti-Catholic propaganda in Eastern Europe. These vampires were bestial, soulless, ravagers of good, virtuous Protestants, and the stories traveled by way of intellectual exchange between the Continent and the British Isles. While there may have been earlier printed stories, the first text in the trajectory we see now is John Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819). Polidori was Lord Byron’s personal physician and traveled with him. During the famous snowed-in horror story writing contest that also resulted in Mary Shelley writing Frankenstein, Polidori wrote The Vampyre, modelling the antagonist, Lord Ruthven, after Byron, with rather unflattering results. Ruthven is sexual, broody, gluttonous, mysterious—a literal Byronic figure. This shaped future vampires, including Count Dracula. In my opinion, the next major contribution to the vampire mythos is the novella Carmilla, by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, which appeared in his collection In a Glass Darkly (1872), and I say this for two reasons. The first, because its antagonist is the first female vampire in English literature, and the second, because it too influenced Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which, like it or not, we must view as the prototype for all future vampires. Le Fanu and Stoker were both Irish writers, contemporaries of one another, and Carmilla pre-dates Dracula by 25 years. There are pronounced similarities in structure (multiple epistolary frames), and the character of a vampire expert/hunter (Doctor Hesselius in Carmilla, Doctor Van Helsing in Dracula). Though Dracula popularized and codified the vampire, Carmilla deserves credit as catalyst. Then, of course, is Dracula (1897). It is hard to talk about Dracula because his name has become synonymous with the vampire itself, one that we are all basically familiar with and so, now I would say, Count Dracula is vanilla vampire—he’s almost become cliché. But, we have to realize that in terms of mass popularity and cultural expectation of the vampire, he is the start. All other future vampires have had to come up with something new and compelling to differentiate themselves from him. From here we have to acknowledge the influence of film in developing the image of the vampire, with two very different takes: Nosferatu (1922) and Horror of Dracula (1958). Nosferatu’s vampire harkens back to the figure’s folkloric origins. It is monstrous, grotesque, not the sexual predator from Polidori, Le Fanu, and Stoker, though the plot was plagiarized from Dracula, to the point at which Stoker’s estate sued for damages after the film’s release. The more influential, I think, was the great Christopher Lee as Dracula, starting with Horror of Dracula. His vampire is sexy, debonair, equally charming and deadly. This image has persisted while the more animalistic version has faded in popularity. While every vampire story adds to the mythology, I’ll say that one of the major turning points in vampire development is the redemptive story arc. As sexy as Dracula is, he is still the antagonist. We don’t root for him, but Mina Harker and Doctor Van Helsing must save the British Empire from this heinous threat. But somewhere along the way, the vampire flipped roles and became the protagonist. Most modern vampire narratives, with a few horror film exceptions like Fright Night and its remake (1985, 2011), have the vampire as the hero. One of the first that comes to mind is Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire (1976), which later was adapted for film (1994). While Lestat is amoral and in keeping with the voracious killer we expect, Louis is sympathetic. He submits to becoming a vampire out of despair and then is appalled by his new world. He’s one of the first examples of a ‘vegetarian’ vampire (to borrow the term from Twilight), who refuses, at least at first, to feed from humans. Others have followed this same trend. Angel, from the Buffy and Angel franchises, is a vampire with a soul, doing good to atone for his past evil; the Cullen clan from Twilight live in a close approximation of a human family and refuse to kill humans; Octavia E. Butler’s brilliant Fledgling (2005) has dark-skinned Shori, of a vampiric species called the Ina, living in symbiotic relationship with her human symbionts rather than killing them; the sleek and sexy Selene of the Underworld series (2003 to the present) fights against the Lycans, leaving humans out of the equation almost completely. These vampires have become the heroes. I think this has been both a delightful expansion of the vampire figure (because who doesn’t love a righteous redemption story?), but also has moved us dangerously away from what was darkly attractive and compelling about the vampire. Novels like Twilight and other young adult fiction have sanitized the vampire. I am hopeful that we can pull back from this trend. Illustration from The Dark Blue by D. H. Friston, 1872, to accompany Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla

JK: What is the current scholarship on the representation of vampires?

DC: Modern scholarship is as diverse as the figure of the vampire itself. Not only does the vampire lurk between fiction pages, but in films, TV shows, web series, and anime and manga. We continue to use traditional explorations of literature, but these approaches, too, are diverse. Feminist and queer theories are staples of examination, but so now are disabilities studies and post-humanism, all of which fall somewhere under a deconstructionist lens. The traditional vampire is Gothic but can also be found in children’s and young adult literature, popular culture, advertisements. Where vampires once embodied the grotesque Other and the dichotomy between Us and Them, and were roundly to be feared and repelled, they are now also marketing tools.

It is impossible to encapsulate and give a clear picture of current scholarship because the vampire is not a static figure. Its infiltration into so many areas of expression is what has given it such an enduring afterlife.

JK: How have the various deconstructionist approaches affected our understanding of literary depictions of vampires?

DC: These different lenses first inform texts that there is something other than able White hetero cis male and that this figure is not central, nor should it be allowed to oppress or erase other narratives. There are so many stories to be told from other perspectives. If we think about vampire origins and what they privileged, we have a Western European-centric citizenry (the heroic male and the vulnerable female) terrorized by the insatiable Eastern European Other. Because deconstructionist disciplines such as critical race theory, gender and queer theories, disability studies and the like are so ubiquitous in academic discourse and have infiltrated mainstream entertainment media, I think we forget that these are relatively new in their social acceptance. And of course, we do encounter pockets of resistance and backlash, glossed as nationalist concerns. What these lenses offer is opportunity for diverse voices to be heard and valued, and to dismantle assumptions that prove inaccurate and even harmful.

JK: Horror characters are often considered to be the personifications of the major fears or the most frightening Other of their respective eras. What sort of fears or Otherness do vampires typically represent?

DC: For many, and certainly for the originators of the vampire, the soul is the seat of one’s being. It is the will, the agency, the individuality of the person. Take that away and you have a monster devoid of humanity and morality. When this was bound up with ideas of religious heresy, the vampire became the figure for damnation.

Le Fanu and Stoker infused political fears of vulnerable national borders, miscegenation and blood-purity into the mix—the vampires literally being foreign invaders stealing and contaminating the blood of British nationals. After this, the vampire has embodied fears of blood-borne disease, racial homogeneity, and more generically whatever else is higher up on the food chain than humans.

JK: How have the critics and readers associated with various underrepresented groups engaged with the concept of Otherness?

DC: I can’t speak for all, but in various interviews and in various wordings, writers like Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, and Octavia E. Butler essentially said that they wrote because they had stories to tell that no one else was telling. I think that is true for many writers and producers today. They are tired of being silent and having to rely on the crumbs of hegemonic narratives to which they can connect. With writers like Morrison and Butler, who veer into the horror/speculative genre, they use what has already been established and accepted by readers—i.e. ghosts, vampires, but adapt them. The Other, then, is reclaimed and expanded so that rather than an oppressive mechanism, it is an empowered one, much like some communities have appropriated derogatory language once directed at them. It may not always be successful, and may still conjure links to that oppressive past, but it is a solid start, and I would say with several successes.

JK: Is it fair to say that the vampire is, in some ways, one of the least horrifying horror archetypes (attractive, mysterious, eloquent, wealthy, etc.)? Do you think the refined aspects emerged due to the nature of the source material used to construct the archetype, the cultural climate in which it was created, or something else entirely?

DC: I think in terms of gross-out horror, then yes, the vampire is one of the least terrifying monster figures, especially as it has come to take on the role of protagonist in recent incarnations, and is, in essence, a supernatural sex symbol. But, if we think about the implications of the vampire, or the classical vampire, then I would say he is quite horrifying—for those who believe in the human soul, to lose that is to lose one’s self. Spike, a sometimes hero, sometimes villain from the Buffyverse said quite tellingly, “Blood is life…Why do you think we eat it? It’s what keeps you going. Makes you warm. Makes you hard. Makes you other than dead.”[i] If you think of the vampire as a prisoner to bloodlust in order to maintain the kind of shadowy half-life in which it exists, and at the end face damnation, or even live in perpetual damnation, then that is, literally, a fate worse than death. It is addiction to the extreme, where the addict has lost his or her agency, and from which there is no lasting cure.

Sure, the vampire can live large while it lasts, and that is the fault of the Byronic vampire who is a seducer, whose wealth accumulates over the centuries, but weigh this against its inhumanity. This is what has been lost, I think, as the vampire has shifted to protagonist. No one wants to think of our hero’s eternal torture, so the narratives have essentially negated it and have turned these vampires into eternal playboys.

JK: What do you think about Marvel’s decision to revive Blade with Mahershala Ali as the new lead? Do you think this decision might have been influenced in any way by the rise in popularity of horror films crafted by African American characters and storytellers, and other recent changes within the film industry?

DC: Blade and Fledgling have been some of the very few literary and filmic vampires of colour, though Blade is a dhampir, a human-vampire hybrid, and Shori, too, is a genetically modified Ina, mixing human and Ina genes, so that is perhaps telling as far as how creators have felt the need to introduce diversity in this genre. Blade, the film, was commercially successful when Wesley Snipes first starred in 1998, but this was well before the phenomenon that is the Marvel Cinematic Universe and the box office success of their superhero franchise. So, I think it is a combination of studio confidence, especially after Black Panther proved that audiences will get behind a racially diverse cast, and Ali’s star being on the rise. There have also been a spate of Black horror and sci-fi films and series—Us, Get Out, and Jordan Peele hosting the revived Twilight Zone series. When Octavia E. Butler was writing (1976-2005) she was a pioneer in Black science fiction. Now, Afro-futurism and writers of colour are gaining the attention and opportunity they have long deserved, and I think this is a wonderful expansion.

JK: Why are varied, complex portrayals of women in the horror genre important?

DC: Varied, complex portrayals of women are important in every genre of every medium. For horror in particular, women have been used as vehicles to express masculine anxiety and frustration, and that is one of the reasons why this genre in particular needs attention.

In early Gothic and horror, women are often the damsels in distress, the hapless victim that motivates the male protagonist, or his threatened possession that he must defend. This is the case with The Vampyre, Carmilla and Dracula.

Interestingly, if we look at the horror film genre, its heyday in the U.S. in the 1980s was directly linked to conservative backlash brought about by increased women’s rights in the workplace and in the fight for reproductive rights, and the sting of military loss in Vietnam, which some saw as demasculinizing. If we take a typical scene in a slasher horror flick, who is the first victim? It’s the busty blonde teen who has just had sex with her boyfriend, and now she is running through the forest in her underwear, and when she trips over a rock, the antagonist stabs her graphically and repeatedly. If that penetrating knife is not a blatant reassertion of phallic dominance, I don’t know what is. Who survives the bloody killer? The quiet girl who kept her legs together. The message is clear here, good girls are chaste and quiet and get to live. Those loud girls, who express their sexuality in any way other than the conservative ideal, deserve to die.

In response to this we have the masculine heroines like Ripley from the Alien franchise, who are essentially men with breasts, and this reversal is equally problematic, but for different reasons. I understand that creators of these media rely on shorthand characterization, but to me, it speaks of sloppy storytelling, and there is definitely a need for nuanced portrayals of women—protagonist, antagonist, sidekick, alien, whatever—just as we’ve seen with male characters. Treat them like the human beings (or alien species, whatever) they are, and the quality and impact of the stories can only grow in power.

JK: Has the broader cultural symbolism of blood impacted the representation of female versus male vampires in different ways? Or has this element acted as a sort of equalizer rather than a source of difference?

DC: I’m not sure if blood has had this impact, but I think other common factors have equalized male and female vampires and given an outlet for some of these historical (and perhaps still relevant) cultural anxieties that I’ve alluded to. Both male and female vampires use (phallic) fangs to penetrate their victims. Interestingly, Stoker made sure that Dracula only fed upon women. Though he contemplates biting Jonathan Harker (and in a draft for American publication this was more evident, though later edited out) he leaves Harker to his vampire brides. His victims are Lucy Westenra and Mina Harker. Stoker feared the homosexual undertones, largely due to the Oscar Wilde sodomy trials that were going on at the time. In Carmilla, when Carmilla bites Laura, it is overtly homosexual, in this case a woman taking the place of a man’s penetrative act on another woman.

In one case, you have a man poaching the women of other men. He must, therefore, be punished. In the other, you have a woman poaching a woman of another man, her father. For this, she must be punished. But this woman on woman scenario also reinforces the troubling stereotype of the insatiable female sexual appetite, which of course must be strictly controlled by men. And the men in Carmilla do this by eventually staking Carmilla (reinserting the phallus into the female body where it rightfully belongs) and decapitating her (castrating her symbolic masculine power). So, female vampires are equally as terrifying and threatening as male vampires, but with the added bonus of playing on and confirming patriarchal fears.

JK: What, in your opinion, would be the best depiction of a female vampire in media and why?

DC: One of my current favourites, and I’m ashamed that it took me so long to read it since I’m a fan of her other work, is Octavia E. Butler’s novel, Fledgling. What Butler does that other contemporary texts have failed to do is imagine the vampire as someone other than Dracula. Shori is a Black vampire who has the appearance of a 10 year-old girl. At the start of the novel she is suffering from amnesia, and her memory disability remains through the entirety of the story, so here we have a brilliant intersection of race, gender, age, and disability.

What is more, rather than kill those upon whom she feeds, Shori and the Ina in general, have adapted their needs and created a symbiotic culture where Ina and their human symbionts live communally—the Ina feed on their humans without killing them and in turn, the human symbionts experience sexual pleasure from the feeding due to toxins in the Inas’ saliva, but also the exchange prolongs the humans’ lives and gives them immunity to most human diseases. Shori’s family has male and female, old and young, multiracial symbionts. Rather than threaten human society like Dracula, these vampires adapt and find a mutually beneficial way coexist. This is one of the most creative adaptations of the vampire mythology that I’ve seen.

Illustration from The Dark Blue by D. H. Friston, 1872, to accompany Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla

JK: What is the current scholarship on the representation of vampires?

DC: Modern scholarship is as diverse as the figure of the vampire itself. Not only does the vampire lurk between fiction pages, but in films, TV shows, web series, and anime and manga. We continue to use traditional explorations of literature, but these approaches, too, are diverse. Feminist and queer theories are staples of examination, but so now are disabilities studies and post-humanism, all of which fall somewhere under a deconstructionist lens. The traditional vampire is Gothic but can also be found in children’s and young adult literature, popular culture, advertisements. Where vampires once embodied the grotesque Other and the dichotomy between Us and Them, and were roundly to be feared and repelled, they are now also marketing tools.

It is impossible to encapsulate and give a clear picture of current scholarship because the vampire is not a static figure. Its infiltration into so many areas of expression is what has given it such an enduring afterlife.

JK: How have the various deconstructionist approaches affected our understanding of literary depictions of vampires?

DC: These different lenses first inform texts that there is something other than able White hetero cis male and that this figure is not central, nor should it be allowed to oppress or erase other narratives. There are so many stories to be told from other perspectives. If we think about vampire origins and what they privileged, we have a Western European-centric citizenry (the heroic male and the vulnerable female) terrorized by the insatiable Eastern European Other. Because deconstructionist disciplines such as critical race theory, gender and queer theories, disability studies and the like are so ubiquitous in academic discourse and have infiltrated mainstream entertainment media, I think we forget that these are relatively new in their social acceptance. And of course, we do encounter pockets of resistance and backlash, glossed as nationalist concerns. What these lenses offer is opportunity for diverse voices to be heard and valued, and to dismantle assumptions that prove inaccurate and even harmful.

JK: Horror characters are often considered to be the personifications of the major fears or the most frightening Other of their respective eras. What sort of fears or Otherness do vampires typically represent?

DC: For many, and certainly for the originators of the vampire, the soul is the seat of one’s being. It is the will, the agency, the individuality of the person. Take that away and you have a monster devoid of humanity and morality. When this was bound up with ideas of religious heresy, the vampire became the figure for damnation.

Le Fanu and Stoker infused political fears of vulnerable national borders, miscegenation and blood-purity into the mix—the vampires literally being foreign invaders stealing and contaminating the blood of British nationals. After this, the vampire has embodied fears of blood-borne disease, racial homogeneity, and more generically whatever else is higher up on the food chain than humans.

JK: How have the critics and readers associated with various underrepresented groups engaged with the concept of Otherness?

DC: I can’t speak for all, but in various interviews and in various wordings, writers like Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, and Octavia E. Butler essentially said that they wrote because they had stories to tell that no one else was telling. I think that is true for many writers and producers today. They are tired of being silent and having to rely on the crumbs of hegemonic narratives to which they can connect. With writers like Morrison and Butler, who veer into the horror/speculative genre, they use what has already been established and accepted by readers—i.e. ghosts, vampires, but adapt them. The Other, then, is reclaimed and expanded so that rather than an oppressive mechanism, it is an empowered one, much like some communities have appropriated derogatory language once directed at them. It may not always be successful, and may still conjure links to that oppressive past, but it is a solid start, and I would say with several successes.

JK: Is it fair to say that the vampire is, in some ways, one of the least horrifying horror archetypes (attractive, mysterious, eloquent, wealthy, etc.)? Do you think the refined aspects emerged due to the nature of the source material used to construct the archetype, the cultural climate in which it was created, or something else entirely?

DC: I think in terms of gross-out horror, then yes, the vampire is one of the least terrifying monster figures, especially as it has come to take on the role of protagonist in recent incarnations, and is, in essence, a supernatural sex symbol. But, if we think about the implications of the vampire, or the classical vampire, then I would say he is quite horrifying—for those who believe in the human soul, to lose that is to lose one’s self. Spike, a sometimes hero, sometimes villain from the Buffyverse said quite tellingly, “Blood is life…Why do you think we eat it? It’s what keeps you going. Makes you warm. Makes you hard. Makes you other than dead.”[i] If you think of the vampire as a prisoner to bloodlust in order to maintain the kind of shadowy half-life in which it exists, and at the end face damnation, or even live in perpetual damnation, then that is, literally, a fate worse than death. It is addiction to the extreme, where the addict has lost his or her agency, and from which there is no lasting cure.

Sure, the vampire can live large while it lasts, and that is the fault of the Byronic vampire who is a seducer, whose wealth accumulates over the centuries, but weigh this against its inhumanity. This is what has been lost, I think, as the vampire has shifted to protagonist. No one wants to think of our hero’s eternal torture, so the narratives have essentially negated it and have turned these vampires into eternal playboys.

JK: What do you think about Marvel’s decision to revive Blade with Mahershala Ali as the new lead? Do you think this decision might have been influenced in any way by the rise in popularity of horror films crafted by African American characters and storytellers, and other recent changes within the film industry?

DC: Blade and Fledgling have been some of the very few literary and filmic vampires of colour, though Blade is a dhampir, a human-vampire hybrid, and Shori, too, is a genetically modified Ina, mixing human and Ina genes, so that is perhaps telling as far as how creators have felt the need to introduce diversity in this genre. Blade, the film, was commercially successful when Wesley Snipes first starred in 1998, but this was well before the phenomenon that is the Marvel Cinematic Universe and the box office success of their superhero franchise. So, I think it is a combination of studio confidence, especially after Black Panther proved that audiences will get behind a racially diverse cast, and Ali’s star being on the rise. There have also been a spate of Black horror and sci-fi films and series—Us, Get Out, and Jordan Peele hosting the revived Twilight Zone series. When Octavia E. Butler was writing (1976-2005) she was a pioneer in Black science fiction. Now, Afro-futurism and writers of colour are gaining the attention and opportunity they have long deserved, and I think this is a wonderful expansion.

JK: Why are varied, complex portrayals of women in the horror genre important?

DC: Varied, complex portrayals of women are important in every genre of every medium. For horror in particular, women have been used as vehicles to express masculine anxiety and frustration, and that is one of the reasons why this genre in particular needs attention.

In early Gothic and horror, women are often the damsels in distress, the hapless victim that motivates the male protagonist, or his threatened possession that he must defend. This is the case with The Vampyre, Carmilla and Dracula.

Interestingly, if we look at the horror film genre, its heyday in the U.S. in the 1980s was directly linked to conservative backlash brought about by increased women’s rights in the workplace and in the fight for reproductive rights, and the sting of military loss in Vietnam, which some saw as demasculinizing. If we take a typical scene in a slasher horror flick, who is the first victim? It’s the busty blonde teen who has just had sex with her boyfriend, and now she is running through the forest in her underwear, and when she trips over a rock, the antagonist stabs her graphically and repeatedly. If that penetrating knife is not a blatant reassertion of phallic dominance, I don’t know what is. Who survives the bloody killer? The quiet girl who kept her legs together. The message is clear here, good girls are chaste and quiet and get to live. Those loud girls, who express their sexuality in any way other than the conservative ideal, deserve to die.

In response to this we have the masculine heroines like Ripley from the Alien franchise, who are essentially men with breasts, and this reversal is equally problematic, but for different reasons. I understand that creators of these media rely on shorthand characterization, but to me, it speaks of sloppy storytelling, and there is definitely a need for nuanced portrayals of women—protagonist, antagonist, sidekick, alien, whatever—just as we’ve seen with male characters. Treat them like the human beings (or alien species, whatever) they are, and the quality and impact of the stories can only grow in power.

JK: Has the broader cultural symbolism of blood impacted the representation of female versus male vampires in different ways? Or has this element acted as a sort of equalizer rather than a source of difference?

DC: I’m not sure if blood has had this impact, but I think other common factors have equalized male and female vampires and given an outlet for some of these historical (and perhaps still relevant) cultural anxieties that I’ve alluded to. Both male and female vampires use (phallic) fangs to penetrate their victims. Interestingly, Stoker made sure that Dracula only fed upon women. Though he contemplates biting Jonathan Harker (and in a draft for American publication this was more evident, though later edited out) he leaves Harker to his vampire brides. His victims are Lucy Westenra and Mina Harker. Stoker feared the homosexual undertones, largely due to the Oscar Wilde sodomy trials that were going on at the time. In Carmilla, when Carmilla bites Laura, it is overtly homosexual, in this case a woman taking the place of a man’s penetrative act on another woman.

In one case, you have a man poaching the women of other men. He must, therefore, be punished. In the other, you have a woman poaching a woman of another man, her father. For this, she must be punished. But this woman on woman scenario also reinforces the troubling stereotype of the insatiable female sexual appetite, which of course must be strictly controlled by men. And the men in Carmilla do this by eventually staking Carmilla (reinserting the phallus into the female body where it rightfully belongs) and decapitating her (castrating her symbolic masculine power). So, female vampires are equally as terrifying and threatening as male vampires, but with the added bonus of playing on and confirming patriarchal fears.

JK: What, in your opinion, would be the best depiction of a female vampire in media and why?

DC: One of my current favourites, and I’m ashamed that it took me so long to read it since I’m a fan of her other work, is Octavia E. Butler’s novel, Fledgling. What Butler does that other contemporary texts have failed to do is imagine the vampire as someone other than Dracula. Shori is a Black vampire who has the appearance of a 10 year-old girl. At the start of the novel she is suffering from amnesia, and her memory disability remains through the entirety of the story, so here we have a brilliant intersection of race, gender, age, and disability.

What is more, rather than kill those upon whom she feeds, Shori and the Ina in general, have adapted their needs and created a symbiotic culture where Ina and their human symbionts live communally—the Ina feed on their humans without killing them and in turn, the human symbionts experience sexual pleasure from the feeding due to toxins in the Inas’ saliva, but also the exchange prolongs the humans’ lives and gives them immunity to most human diseases. Shori’s family has male and female, old and young, multiracial symbionts. Rather than threaten human society like Dracula, these vampires adapt and find a mutually beneficial way coexist. This is one of the most creative adaptations of the vampire mythology that I’ve seen.

—Julija Kalvelytė

From Vlad to Vladislav, from Dracula to Chocula and far beyond, vampires boast perhaps one of the richest and most enduring mythologies amongst a wide variety of cult horror characters. We chat with English and Creative Writing Ph.D. Candidate and Vilnius University lecturer Dr. Dorisa Costello about the complicated history, unused potential, and uncertain future of the immortal—or at least the infinitely adaptable—vampire. This conversation has been edited for clarity.

Julija Kalvelytė: What, if any, stages or crucial works can be identified throughout the evolution and modernization of the classic vampire? How did we get from Stoker’s Vlad to Clement’s Vladislav? Dorisa Costello: First, I have to admit my limitations here, in that I’m only familiar with English-language texts, so there may be major works that I am neglecting. But in terms of the development of the vampire in English-language literature and media, vampires began as oral folklore co-opted as religious, anti-Catholic propaganda in Eastern Europe. These vampires were bestial, soulless, ravagers of good, virtuous Protestants, and the stories traveled by way of intellectual exchange between the Continent and the British Isles. While there may have been earlier printed stories, the first text in the trajectory we see now is John Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819). Polidori was Lord Byron’s personal physician and traveled with him. During the famous snowed-in horror story writing contest that also resulted in Mary Shelley writing Frankenstein, Polidori wrote The Vampyre, modelling the antagonist, Lord Ruthven, after Byron, with rather unflattering results. Ruthven is sexual, broody, gluttonous, mysterious—a literal Byronic figure. This shaped future vampires, including Count Dracula. In my opinion, the next major contribution to the vampire mythos is the novella Carmilla, by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, which appeared in his collection In a Glass Darkly (1872), and I say this for two reasons. The first, because its antagonist is the first female vampire in English literature, and the second, because it too influenced Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which, like it or not, we must view as the prototype for all future vampires. Le Fanu and Stoker were both Irish writers, contemporaries of one another, and Carmilla pre-dates Dracula by 25 years. There are pronounced similarities in structure (multiple epistolary frames), and the character of a vampire expert/hunter (Doctor Hesselius in Carmilla, Doctor Van Helsing in Dracula). Though Dracula popularized and codified the vampire, Carmilla deserves credit as catalyst. Then, of course, is Dracula (1897). It is hard to talk about Dracula because his name has become synonymous with the vampire itself, one that we are all basically familiar with and so, now I would say, Count Dracula is vanilla vampire—he’s almost become cliché. But, we have to realize that in terms of mass popularity and cultural expectation of the vampire, he is the start. All other future vampires have had to come up with something new and compelling to differentiate themselves from him. From here we have to acknowledge the influence of film in developing the image of the vampire, with two very different takes: Nosferatu (1922) and Horror of Dracula (1958). Nosferatu’s vampire harkens back to the figure’s folkloric origins. It is monstrous, grotesque, not the sexual predator from Polidori, Le Fanu, and Stoker, though the plot was plagiarized from Dracula, to the point at which Stoker’s estate sued for damages after the film’s release. The more influential, I think, was the great Christopher Lee as Dracula, starting with Horror of Dracula. His vampire is sexy, debonair, equally charming and deadly. This image has persisted while the more animalistic version has faded in popularity. While every vampire story adds to the mythology, I’ll say that one of the major turning points in vampire development is the redemptive story arc. As sexy as Dracula is, he is still the antagonist. We don’t root for him, but Mina Harker and Doctor Van Helsing must save the British Empire from this heinous threat. But somewhere along the way, the vampire flipped roles and became the protagonist. Most modern vampire narratives, with a few horror film exceptions like Fright Night and its remake (1985, 2011), have the vampire as the hero. One of the first that comes to mind is Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire (1976), which later was adapted for film (1994). While Lestat is amoral and in keeping with the voracious killer we expect, Louis is sympathetic. He submits to becoming a vampire out of despair and then is appalled by his new world. He’s one of the first examples of a ‘vegetarian’ vampire (to borrow the term from Twilight), who refuses, at least at first, to feed from humans. Others have followed this same trend. Angel, from the Buffy and Angel franchises, is a vampire with a soul, doing good to atone for his past evil; the Cullen clan from Twilight live in a close approximation of a human family and refuse to kill humans; Octavia E. Butler’s brilliant Fledgling (2005) has dark-skinned Shori, of a vampiric species called the Ina, living in symbiotic relationship with her human symbionts rather than killing them; the sleek and sexy Selene of the Underworld series (2003 to the present) fights against the Lycans, leaving humans out of the equation almost completely. These vampires have become the heroes. I think this has been both a delightful expansion of the vampire figure (because who doesn’t love a righteous redemption story?), but also has moved us dangerously away from what was darkly attractive and compelling about the vampire. Novels like Twilight and other young adult fiction have sanitized the vampire. I am hopeful that we can pull back from this trend.

While every vampire story adds to the mythology, I’ll say that one of the major turning points in vampire development is the redemptive story arc. As sexy as Dracula is, he is still the antagonist. We don’t root for him, but Mina Harker and Doctor Van Helsing must save the British Empire from this heinous threat. But somewhere along the way, the vampire flipped roles and became the protagonist.Julija Kalvelytė: Why have you decided to tackle this topic now and not, for example, during the golden days of Twilight? Dorisa Costello: The Twilight series was actually the culmination of the vampire in young adult literature. American author L.J. Smith’s The Vampire Diaries of the 1990s was popular well before that (and was turned into a television series starting in 2009). Buffy the Vampire Slayer and its spin-off, Angel, still has mass followings. I think now is a time to reflect on the young adult phenomenon rather than be swept away by it. My opinion is that, while certainly commercially popular, the Twilight novels and films actually set the vampire back in terms of the kind of cultural power it could command. The Twilight novels deliver a stereotypical damsel in distress with Bella Swan, and actually reinforce male privilege in the stalking-as-romance trope. Edward Cullen is a Peeping Tom who invades Bella’s bedroom to watch her sleep, is jealously possessive, and yet when he leaves her “for her own good,” continues to monitor her and not allow her to move on to a new lover. He is an emotionally abusive boyfriend imbued with superhuman abilities. And, rather than provide the teenage girls, who are the majority of readership of these books, with a strong young woman to emulate, Bella is klutzy, whiny, in constant need of rescue, and only comes into her own power (a power saturated in traditional female domesticity and Puritan virtue) once she is transformed into a vampire by external forces. It is not a power she discovers within, but one granted to her by her husband, tied exclusively to her role as mother. Now that the popularity of Twilight has waned and vampires as a figure have taken somewhat of a break, I’m hopeful that clever, provocative stories can emerge, which is really in keeping with the tradition of the vampire anyway. JK: Some sources associate vampires with the dandy subculture and the certain type of masculinity it represents. How has this particular subculture influenced the vampire archetype? DC: Though Dracula was intentionally heterosexual, more recent manifestations of the male vampire have become, if anything, pansexual, playing up the effeminate side that Stoker purposefully suppressed because of his previous associations with, and admiration of, Oscar Wilde. I think the dandyism and open sexuality is meant to compliment the hedonism and indulgence that vampires possess. They are, in many ways, above the laws of mortal man. They can kill whom they please, have sex with whom they please, accrue wealth over centuries, and so partake in whatever desires they please. [gallery columns="2" size="full" link="none" ids="11898,11899"] This decadence and indulgence is often shorthanded in texts as foppish tells—luxurious clothes that harken back to previous eras of silk, lace, velvet doublets, and capes; mansions bedecked with candelabras and damasked curtains that obscure the pallor of their faces, but also lend an air of wealth, mystery, and often a sense of ennui; sensual movements that belie preternatural speed and strength. There is an alternate narrative to explain the effete male vampire - that he is sexually impotent, a eunuch. This has its roots in the Osiris myth of ancient Egypt, which some connect to vampires. Osiris was murdered by his brother Set, and to guarantee he would not return from the underworld, his body was chopped into pieces that were scattered all over the world. Isis, Osiris’ sister and wife, was able to find all the pieces except for his penis. She reassembled him and brought him back from the dead, hence his association with vampires, but without his manhood intact. Angel, from the Buffyverse, addresses this myth with some comedic discomfort, repeating throughout one episode that he does in fact have a penis and he is not impotent. Angel is the antithesis of the dandy vamp. He is tall, dark, handsome, muscled, suave, and seems to think jeans, a T-shirt, and a black leather jacket are the height of fashion—though, black leather is admittedly cool. The hang-up for him is the curse on him that should he experience a moment of happiness, he will lose his soul once again and revert to the vicious, amoral Angelus. Apparently, sex with Buffy is the key to his happiness, and so his love life has been severely curbed, with the exception of fathering a child with the vampire, Darla. Nonetheless, his overt masculinity is at odds with the effeminate vampire, like Interview with the Vampire’s Armand. JK: If the dandy can be viewed as a sort of broad, abstract real-world source of inspiration for the male vampire, could female characters also be associated with this subculture? If not, what real-world subcultures or groups are female vampires most commonly considered to be inspired by or associated with? DC: Female vampires, especially modern ones, have clear parallels with the femme fatale archetype. Her sexuality is part of her allure and part of her threat. This is true for Carmilla, and Selene from the Underworld films mixes this with what we usually see in male heroes, which is physical prowess. She is a living weapon in her role of Death Dealer. JK: Female sexuality seems to be quite heavily emphasized in many works depicting vampires. What are the major factors that originally established this theme and perpetuated it for such a long time? DC: Oh, goodness, where do I start? One of the most important reasons why we see the female vampire as a figure of threatening sexuality is because women were (are) seen as figures of threatening sexuality. In the Victorian era, and well before, Britain was struggling with women’s legal rights, like being able to own property, work outside the home, sue for divorce and custody of their children, and vote. Women’s sexuality in particular was still problematic because of issues of paternity—the mother was the one who could guarantee legitimacy of heirs for inheritance and titles, and so the rigid control of that sexuality, compounded by stereotypes that she’s already a hysterical and sexual maniac, is primary in almost every governing institution of the time. We still see the implications of these stereotypes in the virgin/whore dichotomy, as well as victim blaming for sexual assault. Our law enforcement and judiciary imply that the woman asked for the assault because of her own provocative nature—what was she wearing? Was she intoxicated? Had she been flirting with him earlier? Well, then of course she deserved it. It is Eve tempting Adam to sin with forbidden fruit. From these dangerous ideas it is only a skip and a jump to overlaying the sexual fiend that is natural Woman with a literary fiend whose sexuality entices her victims into her hellish clutches, and then drains him dry. We also have the lesbian aspect of female vampires feeding on female victims, which Carmilla touches on to a certain extent, but unfortunately pulls back from and reinforces heteronormative ideals. Other female vampire characters are openly bisexual or lesbian, but this is often to tantalize the male gaze like most lesbian pornography, and is not a genuine treatment. The web series adaptation of Carmilla, though, is much more open to exploring fluidity of gender and sexuality. JK: With media products focused on genuine, nuanced depictions of historically underrepresented groups, we often hear the argument that they'll never sell. How has the Carmilla web series managed to depict gender and sexuality in a way that is both authentic and commercially successful? DC: There are probably a lot of external factors that contributed to Carmilla the web series’ popularity—readily available digital format, fans hungering for more progressive and inclusive representation, legal reform and more open social consciousness—but it is still, unfortunately, limited popularity. Critical and commercial success are not always the same, and in this case, it is largely the online fans that have propelled Carmilla the Movie (2017), which was crowdfunded for its initial production. While it is available for digital download, the movie only had a one-day theatrical release in Canada, so it is hardly raking in the big bucks. So, are the media execs right that these films won’t sell? Kind of. There seems to be still some reluctance to produce well-funded and high-quality queer content, though this is changing with critical and (moderate) commercial successes like Moonlight, Carol, and Call Me By Your Name. On the whole, I think queer writers and producers are telling their authentic stories, and audiences are sensing that authenticity. That, I think, is most important. Audiences want stories that resonate ‘the real,’ not necessarily in terms of realistic worlds and characters (I mean, we’re talking about vampires, here), but in tapping into the emotions and struggles that are universal at their core—love, fear, acceptance, hope—but are sheathed in the nuanced details of differently lived lives. We’ve seen this happen with ethnically diverse stories, and it is only a matter of time before sexually diverse stories are equally normalized.

Audiences want stories that resonate ‘the real,’ not necessarily in terms of realistic worlds and characters [...], but in tapping into the emotions and struggles that are universal at their core—love, fear, acceptance, hope—but are sheathed in the nuanced details of differently lived lives.JK: In recent years, there has been a general shift within literature, film, and media towards more inclusivity and varied, diverse representation. Is the vampire archetype difficult to ‘diversify’ for any particular reason and how much has purist gatekeeping affected attempts to make such changes? DC: I think we have entered a time, certainly more so than in the past, where producers and consumers of media texts have greater freedom and opportunity for variety, and this is all to the good. Diversity is a representation of our reality, and it is about time that we were open to that truth, rather than curating an image of artificial homogeneity and elitism. The vampire has already expanded in this direction, and I think it is perfectly suited for the task. The politically motivated Blaxploitation films of the 1970s produced Blackula (1972), Blade and Fledgling have Black protagonist vampires. Carmilla is a lesbian vampire, and adaptations of the novel have been made in film and as a web series. I don’t see any reason why the vampire cannot continue to reflect the needs of its age, just as it always has.

Illustration from The Dark Blue by D. H. Friston, 1872, to accompany Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla

JK: What is the current scholarship on the representation of vampires?

DC: Modern scholarship is as diverse as the figure of the vampire itself. Not only does the vampire lurk between fiction pages, but in films, TV shows, web series, and anime and manga. We continue to use traditional explorations of literature, but these approaches, too, are diverse. Feminist and queer theories are staples of examination, but so now are disabilities studies and post-humanism, all of which fall somewhere under a deconstructionist lens. The traditional vampire is Gothic but can also be found in children’s and young adult literature, popular culture, advertisements. Where vampires once embodied the grotesque Other and the dichotomy between Us and Them, and were roundly to be feared and repelled, they are now also marketing tools.

It is impossible to encapsulate and give a clear picture of current scholarship because the vampire is not a static figure. Its infiltration into so many areas of expression is what has given it such an enduring afterlife.

JK: How have the various deconstructionist approaches affected our understanding of literary depictions of vampires?

DC: These different lenses first inform texts that there is something other than able White hetero cis male and that this figure is not central, nor should it be allowed to oppress or erase other narratives. There are so many stories to be told from other perspectives. If we think about vampire origins and what they privileged, we have a Western European-centric citizenry (the heroic male and the vulnerable female) terrorized by the insatiable Eastern European Other. Because deconstructionist disciplines such as critical race theory, gender and queer theories, disability studies and the like are so ubiquitous in academic discourse and have infiltrated mainstream entertainment media, I think we forget that these are relatively new in their social acceptance. And of course, we do encounter pockets of resistance and backlash, glossed as nationalist concerns. What these lenses offer is opportunity for diverse voices to be heard and valued, and to dismantle assumptions that prove inaccurate and even harmful.

JK: Horror characters are often considered to be the personifications of the major fears or the most frightening Other of their respective eras. What sort of fears or Otherness do vampires typically represent?

DC: For many, and certainly for the originators of the vampire, the soul is the seat of one’s being. It is the will, the agency, the individuality of the person. Take that away and you have a monster devoid of humanity and morality. When this was bound up with ideas of religious heresy, the vampire became the figure for damnation.

Le Fanu and Stoker infused political fears of vulnerable national borders, miscegenation and blood-purity into the mix—the vampires literally being foreign invaders stealing and contaminating the blood of British nationals. After this, the vampire has embodied fears of blood-borne disease, racial homogeneity, and more generically whatever else is higher up on the food chain than humans.

JK: How have the critics and readers associated with various underrepresented groups engaged with the concept of Otherness?

DC: I can’t speak for all, but in various interviews and in various wordings, writers like Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, and Octavia E. Butler essentially said that they wrote because they had stories to tell that no one else was telling. I think that is true for many writers and producers today. They are tired of being silent and having to rely on the crumbs of hegemonic narratives to which they can connect. With writers like Morrison and Butler, who veer into the horror/speculative genre, they use what has already been established and accepted by readers—i.e. ghosts, vampires, but adapt them. The Other, then, is reclaimed and expanded so that rather than an oppressive mechanism, it is an empowered one, much like some communities have appropriated derogatory language once directed at them. It may not always be successful, and may still conjure links to that oppressive past, but it is a solid start, and I would say with several successes.

JK: Is it fair to say that the vampire is, in some ways, one of the least horrifying horror archetypes (attractive, mysterious, eloquent, wealthy, etc.)? Do you think the refined aspects emerged due to the nature of the source material used to construct the archetype, the cultural climate in which it was created, or something else entirely?

DC: I think in terms of gross-out horror, then yes, the vampire is one of the least terrifying monster figures, especially as it has come to take on the role of protagonist in recent incarnations, and is, in essence, a supernatural sex symbol. But, if we think about the implications of the vampire, or the classical vampire, then I would say he is quite horrifying—for those who believe in the human soul, to lose that is to lose one’s self. Spike, a sometimes hero, sometimes villain from the Buffyverse said quite tellingly, “Blood is life…Why do you think we eat it? It’s what keeps you going. Makes you warm. Makes you hard. Makes you other than dead.”[i] If you think of the vampire as a prisoner to bloodlust in order to maintain the kind of shadowy half-life in which it exists, and at the end face damnation, or even live in perpetual damnation, then that is, literally, a fate worse than death. It is addiction to the extreme, where the addict has lost his or her agency, and from which there is no lasting cure.

Sure, the vampire can live large while it lasts, and that is the fault of the Byronic vampire who is a seducer, whose wealth accumulates over the centuries, but weigh this against its inhumanity. This is what has been lost, I think, as the vampire has shifted to protagonist. No one wants to think of our hero’s eternal torture, so the narratives have essentially negated it and have turned these vampires into eternal playboys.

JK: What do you think about Marvel’s decision to revive Blade with Mahershala Ali as the new lead? Do you think this decision might have been influenced in any way by the rise in popularity of horror films crafted by African American characters and storytellers, and other recent changes within the film industry?

DC: Blade and Fledgling have been some of the very few literary and filmic vampires of colour, though Blade is a dhampir, a human-vampire hybrid, and Shori, too, is a genetically modified Ina, mixing human and Ina genes, so that is perhaps telling as far as how creators have felt the need to introduce diversity in this genre. Blade, the film, was commercially successful when Wesley Snipes first starred in 1998, but this was well before the phenomenon that is the Marvel Cinematic Universe and the box office success of their superhero franchise. So, I think it is a combination of studio confidence, especially after Black Panther proved that audiences will get behind a racially diverse cast, and Ali’s star being on the rise. There have also been a spate of Black horror and sci-fi films and series—Us, Get Out, and Jordan Peele hosting the revived Twilight Zone series. When Octavia E. Butler was writing (1976-2005) she was a pioneer in Black science fiction. Now, Afro-futurism and writers of colour are gaining the attention and opportunity they have long deserved, and I think this is a wonderful expansion.

JK: Why are varied, complex portrayals of women in the horror genre important?

DC: Varied, complex portrayals of women are important in every genre of every medium. For horror in particular, women have been used as vehicles to express masculine anxiety and frustration, and that is one of the reasons why this genre in particular needs attention.

In early Gothic and horror, women are often the damsels in distress, the hapless victim that motivates the male protagonist, or his threatened possession that he must defend. This is the case with The Vampyre, Carmilla and Dracula.

Interestingly, if we look at the horror film genre, its heyday in the U.S. in the 1980s was directly linked to conservative backlash brought about by increased women’s rights in the workplace and in the fight for reproductive rights, and the sting of military loss in Vietnam, which some saw as demasculinizing. If we take a typical scene in a slasher horror flick, who is the first victim? It’s the busty blonde teen who has just had sex with her boyfriend, and now she is running through the forest in her underwear, and when she trips over a rock, the antagonist stabs her graphically and repeatedly. If that penetrating knife is not a blatant reassertion of phallic dominance, I don’t know what is. Who survives the bloody killer? The quiet girl who kept her legs together. The message is clear here, good girls are chaste and quiet and get to live. Those loud girls, who express their sexuality in any way other than the conservative ideal, deserve to die.

In response to this we have the masculine heroines like Ripley from the Alien franchise, who are essentially men with breasts, and this reversal is equally problematic, but for different reasons. I understand that creators of these media rely on shorthand characterization, but to me, it speaks of sloppy storytelling, and there is definitely a need for nuanced portrayals of women—protagonist, antagonist, sidekick, alien, whatever—just as we’ve seen with male characters. Treat them like the human beings (or alien species, whatever) they are, and the quality and impact of the stories can only grow in power.

JK: Has the broader cultural symbolism of blood impacted the representation of female versus male vampires in different ways? Or has this element acted as a sort of equalizer rather than a source of difference?

DC: I’m not sure if blood has had this impact, but I think other common factors have equalized male and female vampires and given an outlet for some of these historical (and perhaps still relevant) cultural anxieties that I’ve alluded to. Both male and female vampires use (phallic) fangs to penetrate their victims. Interestingly, Stoker made sure that Dracula only fed upon women. Though he contemplates biting Jonathan Harker (and in a draft for American publication this was more evident, though later edited out) he leaves Harker to his vampire brides. His victims are Lucy Westenra and Mina Harker. Stoker feared the homosexual undertones, largely due to the Oscar Wilde sodomy trials that were going on at the time. In Carmilla, when Carmilla bites Laura, it is overtly homosexual, in this case a woman taking the place of a man’s penetrative act on another woman.

In one case, you have a man poaching the women of other men. He must, therefore, be punished. In the other, you have a woman poaching a woman of another man, her father. For this, she must be punished. But this woman on woman scenario also reinforces the troubling stereotype of the insatiable female sexual appetite, which of course must be strictly controlled by men. And the men in Carmilla do this by eventually staking Carmilla (reinserting the phallus into the female body where it rightfully belongs) and decapitating her (castrating her symbolic masculine power). So, female vampires are equally as terrifying and threatening as male vampires, but with the added bonus of playing on and confirming patriarchal fears.

JK: What, in your opinion, would be the best depiction of a female vampire in media and why?

DC: One of my current favourites, and I’m ashamed that it took me so long to read it since I’m a fan of her other work, is Octavia E. Butler’s novel, Fledgling. What Butler does that other contemporary texts have failed to do is imagine the vampire as someone other than Dracula. Shori is a Black vampire who has the appearance of a 10 year-old girl. At the start of the novel she is suffering from amnesia, and her memory disability remains through the entirety of the story, so here we have a brilliant intersection of race, gender, age, and disability.

What is more, rather than kill those upon whom she feeds, Shori and the Ina in general, have adapted their needs and created a symbiotic culture where Ina and their human symbionts live communally—the Ina feed on their humans without killing them and in turn, the human symbionts experience sexual pleasure from the feeding due to toxins in the Inas’ saliva, but also the exchange prolongs the humans’ lives and gives them immunity to most human diseases. Shori’s family has male and female, old and young, multiracial symbionts. Rather than threaten human society like Dracula, these vampires adapt and find a mutually beneficial way coexist. This is one of the most creative adaptations of the vampire mythology that I’ve seen.

Illustration from The Dark Blue by D. H. Friston, 1872, to accompany Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla

JK: What is the current scholarship on the representation of vampires?

DC: Modern scholarship is as diverse as the figure of the vampire itself. Not only does the vampire lurk between fiction pages, but in films, TV shows, web series, and anime and manga. We continue to use traditional explorations of literature, but these approaches, too, are diverse. Feminist and queer theories are staples of examination, but so now are disabilities studies and post-humanism, all of which fall somewhere under a deconstructionist lens. The traditional vampire is Gothic but can also be found in children’s and young adult literature, popular culture, advertisements. Where vampires once embodied the grotesque Other and the dichotomy between Us and Them, and were roundly to be feared and repelled, they are now also marketing tools.

It is impossible to encapsulate and give a clear picture of current scholarship because the vampire is not a static figure. Its infiltration into so many areas of expression is what has given it such an enduring afterlife.

JK: How have the various deconstructionist approaches affected our understanding of literary depictions of vampires?

DC: These different lenses first inform texts that there is something other than able White hetero cis male and that this figure is not central, nor should it be allowed to oppress or erase other narratives. There are so many stories to be told from other perspectives. If we think about vampire origins and what they privileged, we have a Western European-centric citizenry (the heroic male and the vulnerable female) terrorized by the insatiable Eastern European Other. Because deconstructionist disciplines such as critical race theory, gender and queer theories, disability studies and the like are so ubiquitous in academic discourse and have infiltrated mainstream entertainment media, I think we forget that these are relatively new in their social acceptance. And of course, we do encounter pockets of resistance and backlash, glossed as nationalist concerns. What these lenses offer is opportunity for diverse voices to be heard and valued, and to dismantle assumptions that prove inaccurate and even harmful.

JK: Horror characters are often considered to be the personifications of the major fears or the most frightening Other of their respective eras. What sort of fears or Otherness do vampires typically represent?

DC: For many, and certainly for the originators of the vampire, the soul is the seat of one’s being. It is the will, the agency, the individuality of the person. Take that away and you have a monster devoid of humanity and morality. When this was bound up with ideas of religious heresy, the vampire became the figure for damnation.

Le Fanu and Stoker infused political fears of vulnerable national borders, miscegenation and blood-purity into the mix—the vampires literally being foreign invaders stealing and contaminating the blood of British nationals. After this, the vampire has embodied fears of blood-borne disease, racial homogeneity, and more generically whatever else is higher up on the food chain than humans.

JK: How have the critics and readers associated with various underrepresented groups engaged with the concept of Otherness?

DC: I can’t speak for all, but in various interviews and in various wordings, writers like Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, and Octavia E. Butler essentially said that they wrote because they had stories to tell that no one else was telling. I think that is true for many writers and producers today. They are tired of being silent and having to rely on the crumbs of hegemonic narratives to which they can connect. With writers like Morrison and Butler, who veer into the horror/speculative genre, they use what has already been established and accepted by readers—i.e. ghosts, vampires, but adapt them. The Other, then, is reclaimed and expanded so that rather than an oppressive mechanism, it is an empowered one, much like some communities have appropriated derogatory language once directed at them. It may not always be successful, and may still conjure links to that oppressive past, but it is a solid start, and I would say with several successes.

JK: Is it fair to say that the vampire is, in some ways, one of the least horrifying horror archetypes (attractive, mysterious, eloquent, wealthy, etc.)? Do you think the refined aspects emerged due to the nature of the source material used to construct the archetype, the cultural climate in which it was created, or something else entirely?

DC: I think in terms of gross-out horror, then yes, the vampire is one of the least terrifying monster figures, especially as it has come to take on the role of protagonist in recent incarnations, and is, in essence, a supernatural sex symbol. But, if we think about the implications of the vampire, or the classical vampire, then I would say he is quite horrifying—for those who believe in the human soul, to lose that is to lose one’s self. Spike, a sometimes hero, sometimes villain from the Buffyverse said quite tellingly, “Blood is life…Why do you think we eat it? It’s what keeps you going. Makes you warm. Makes you hard. Makes you other than dead.”[i] If you think of the vampire as a prisoner to bloodlust in order to maintain the kind of shadowy half-life in which it exists, and at the end face damnation, or even live in perpetual damnation, then that is, literally, a fate worse than death. It is addiction to the extreme, where the addict has lost his or her agency, and from which there is no lasting cure.

Sure, the vampire can live large while it lasts, and that is the fault of the Byronic vampire who is a seducer, whose wealth accumulates over the centuries, but weigh this against its inhumanity. This is what has been lost, I think, as the vampire has shifted to protagonist. No one wants to think of our hero’s eternal torture, so the narratives have essentially negated it and have turned these vampires into eternal playboys.

JK: What do you think about Marvel’s decision to revive Blade with Mahershala Ali as the new lead? Do you think this decision might have been influenced in any way by the rise in popularity of horror films crafted by African American characters and storytellers, and other recent changes within the film industry?

DC: Blade and Fledgling have been some of the very few literary and filmic vampires of colour, though Blade is a dhampir, a human-vampire hybrid, and Shori, too, is a genetically modified Ina, mixing human and Ina genes, so that is perhaps telling as far as how creators have felt the need to introduce diversity in this genre. Blade, the film, was commercially successful when Wesley Snipes first starred in 1998, but this was well before the phenomenon that is the Marvel Cinematic Universe and the box office success of their superhero franchise. So, I think it is a combination of studio confidence, especially after Black Panther proved that audiences will get behind a racially diverse cast, and Ali’s star being on the rise. There have also been a spate of Black horror and sci-fi films and series—Us, Get Out, and Jordan Peele hosting the revived Twilight Zone series. When Octavia E. Butler was writing (1976-2005) she was a pioneer in Black science fiction. Now, Afro-futurism and writers of colour are gaining the attention and opportunity they have long deserved, and I think this is a wonderful expansion.

JK: Why are varied, complex portrayals of women in the horror genre important?

DC: Varied, complex portrayals of women are important in every genre of every medium. For horror in particular, women have been used as vehicles to express masculine anxiety and frustration, and that is one of the reasons why this genre in particular needs attention.

In early Gothic and horror, women are often the damsels in distress, the hapless victim that motivates the male protagonist, or his threatened possession that he must defend. This is the case with The Vampyre, Carmilla and Dracula.

Interestingly, if we look at the horror film genre, its heyday in the U.S. in the 1980s was directly linked to conservative backlash brought about by increased women’s rights in the workplace and in the fight for reproductive rights, and the sting of military loss in Vietnam, which some saw as demasculinizing. If we take a typical scene in a slasher horror flick, who is the first victim? It’s the busty blonde teen who has just had sex with her boyfriend, and now she is running through the forest in her underwear, and when she trips over a rock, the antagonist stabs her graphically and repeatedly. If that penetrating knife is not a blatant reassertion of phallic dominance, I don’t know what is. Who survives the bloody killer? The quiet girl who kept her legs together. The message is clear here, good girls are chaste and quiet and get to live. Those loud girls, who express their sexuality in any way other than the conservative ideal, deserve to die.

In response to this we have the masculine heroines like Ripley from the Alien franchise, who are essentially men with breasts, and this reversal is equally problematic, but for different reasons. I understand that creators of these media rely on shorthand characterization, but to me, it speaks of sloppy storytelling, and there is definitely a need for nuanced portrayals of women—protagonist, antagonist, sidekick, alien, whatever—just as we’ve seen with male characters. Treat them like the human beings (or alien species, whatever) they are, and the quality and impact of the stories can only grow in power.

JK: Has the broader cultural symbolism of blood impacted the representation of female versus male vampires in different ways? Or has this element acted as a sort of equalizer rather than a source of difference?

DC: I’m not sure if blood has had this impact, but I think other common factors have equalized male and female vampires and given an outlet for some of these historical (and perhaps still relevant) cultural anxieties that I’ve alluded to. Both male and female vampires use (phallic) fangs to penetrate their victims. Interestingly, Stoker made sure that Dracula only fed upon women. Though he contemplates biting Jonathan Harker (and in a draft for American publication this was more evident, though later edited out) he leaves Harker to his vampire brides. His victims are Lucy Westenra and Mina Harker. Stoker feared the homosexual undertones, largely due to the Oscar Wilde sodomy trials that were going on at the time. In Carmilla, when Carmilla bites Laura, it is overtly homosexual, in this case a woman taking the place of a man’s penetrative act on another woman.

In one case, you have a man poaching the women of other men. He must, therefore, be punished. In the other, you have a woman poaching a woman of another man, her father. For this, she must be punished. But this woman on woman scenario also reinforces the troubling stereotype of the insatiable female sexual appetite, which of course must be strictly controlled by men. And the men in Carmilla do this by eventually staking Carmilla (reinserting the phallus into the female body where it rightfully belongs) and decapitating her (castrating her symbolic masculine power). So, female vampires are equally as terrifying and threatening as male vampires, but with the added bonus of playing on and confirming patriarchal fears.

JK: What, in your opinion, would be the best depiction of a female vampire in media and why?

DC: One of my current favourites, and I’m ashamed that it took me so long to read it since I’m a fan of her other work, is Octavia E. Butler’s novel, Fledgling. What Butler does that other contemporary texts have failed to do is imagine the vampire as someone other than Dracula. Shori is a Black vampire who has the appearance of a 10 year-old girl. At the start of the novel she is suffering from amnesia, and her memory disability remains through the entirety of the story, so here we have a brilliant intersection of race, gender, age, and disability.

What is more, rather than kill those upon whom she feeds, Shori and the Ina in general, have adapted their needs and created a symbiotic culture where Ina and their human symbionts live communally—the Ina feed on their humans without killing them and in turn, the human symbionts experience sexual pleasure from the feeding due to toxins in the Inas’ saliva, but also the exchange prolongs the humans’ lives and gives them immunity to most human diseases. Shori’s family has male and female, old and young, multiracial symbionts. Rather than threaten human society like Dracula, these vampires adapt and find a mutually beneficial way coexist. This is one of the most creative adaptations of the vampire mythology that I’ve seen.