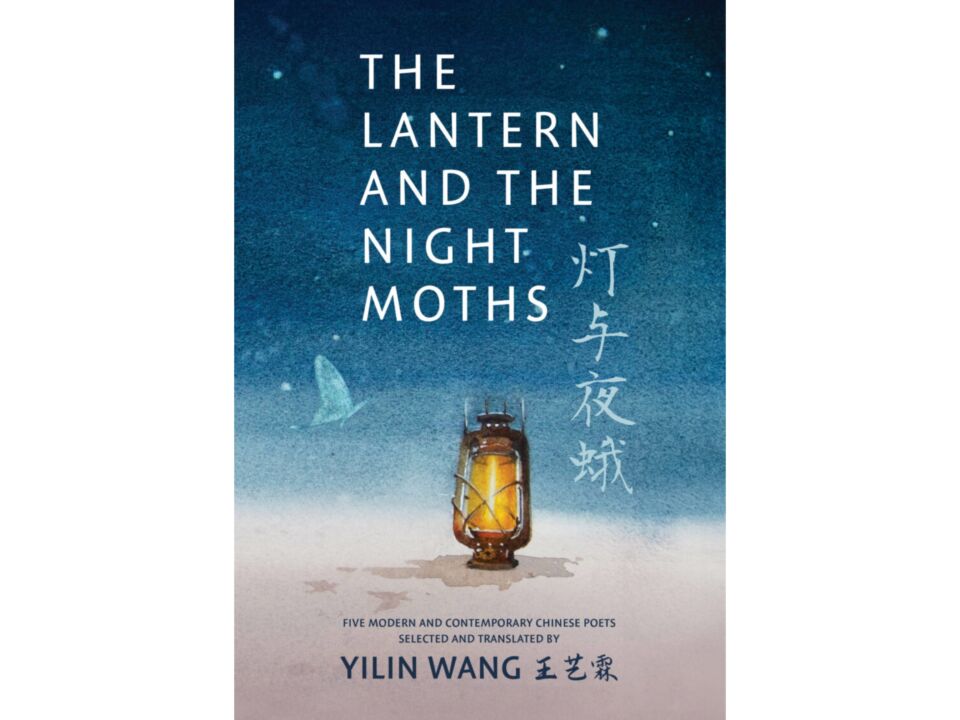

The Space Between: A Review of The Lantern and the Night Moths by Yilin Wang

When I first started asking myself the questions that led me to identify on the asexual spectrum—the multifaceted space of queer identities that comprise the asexual community—it was a powerful, self-affirming experience. I gained the language to better understand myself, but it also brought into focus how isolated and disconnected I was from many around me. This journey drew me to The Lantern and the Night Moths, a compilation of selected works by five Chinese poets, translated by Yilin Wang (she/they), an award-winning Chinese diaspora poet-translator currently living in Vancouver. I never expected to feel so intimately connected to poets living in spaces and times that felt so removed from my own. Yet, through their words and Wang’s thoughtful translations, I felt genuinely seen and heard in my own lived experience.

Each poet is presented in a section with five to six selected poems, where both the original Chinese text and Wang’s English translation are featured side by side. Immediately engaging with both versions feels like I’m being part of a conversation between the poet and the translator. The back of the book offers short biographies of each of the selected poets, and for readers who want to go further, Wang also provides bonus materials on their website, including a Spotify playlist, a pronunciation guide for the names of the poets, and even a bingo game introducing classical Chinese poetry motifs that appear in the text. This novel and engaging method allow readers to gain another level of cultural immersion and interaction with the work.

These five poets—Qiu Jin, Ziang Qiaohui, Fei Ming, Xiao Xi and Dai Wangshu—offer insights into Chinese poetry rooted in classical traditions while being boldly innovative and modern. Wang’s translations further open this world to Anglophone readers. Engaging with these poets and their work also means engaging with their translator. Wang creates a space for this gathering through moving personal essays that bookend each poet’s section. In these essays, Wang speaks to the historical background of each poet’s life and work, the challenges and delights of translation and how interacting with these poets has affected Wang’s own life. These essays provided me with an intimate picture of Wang’s experience with queerness and their search for connection, which, in many ways, mirrored my own.

"I wait alone in this room for your voice to rise from among the pages, slowly, to cross time and distance."

Qiu Jin (1875–1907) is the first poet we meet. A figure in Chinese history known for her fight for women’s rights during the imperial Qing Dynasty, her work ultimately led up to her being immortalized as a feminist martyr. Qiu is seen as a revolutionary who worked toward overthrowing the oppressive government of her time, but her lesser-known literary writing also speaks to her power as an orator and writer. Here, her poetry expresses thoughts that I remember having when I started to question my assumptions about sexuality and gender.

The opening poem, entitled “A River of Crimson: A Brief Stay in the Glorious Capital,” speaks to Qiu’s struggle to exist in a world that does not understand her and actively works to contain her within traditional gender roles. “Bitterly forced to behave as a wife with painted brows, / I’m full of disdain!” She says of her life, one marked by resistance to norms that bind her to heteronormative and amatonormative expectations. Defiantly, she aspires to transcend such shackles. “Not a man in the flesh, unable to walk among them; / but the heart exceeds, / more fierce than a man’s!” When she asks, “How can narrow, uncultivated minds / comprehend my nature?” I feel her channeling the frustration of many in the asexual, aromantic, and wider queer community who continue to push back against restrictive stereotypes.

Her struggle is even louder in “Inscription on My Tiny Portrait (in Men’s Clothes),” but here it is offered with the hope that the fight for an authentic life—true to one’s own inner nature (and to my mind, inner queerness)—contains the promise of a better time to come. “The physical masculinity of a deceased self is mere illusion, / but the envisioned future can become reality.” Reading this makes me think of trans authors such as Rowan Jette Knox and Thomas Page McBee, who have written about their struggles to reach that envisioned future for themselves, whose stories continue to speak to the fallaciousness of toxic masculinity.

The lines, “Regretting that we didn’t know each other sooner, let us unite, / heads held up high sighing at the times, spirits emboldened,” read as a powerful message of solidarity that stretches across the century that separates her from us. Wang notes this poem was inscribed on the back of a photo of Qiu cross-dressing in traditional late Qing Dynasty men’s clothing. It is a fitting vessel for her words in our present, at a time when anti-trans and anti-drag political actions have reached a fever pitch in North America and the UK.

Qiu Jin also speaks to a longing for a relationship with someone with whom she can share her heart in ways not rooted in normative ideals of romance and sexuality. In “Pusaman: To a Female Friend,” she expresses a desire for someone “to converse on matters lingering within one’s heart” or a person who shares her tune—a “kindred spirit who cherishes the same songs” as spoken of in “Spontaneous Thoughts.” “In this crimson-dust world, where can I find my kindred spirit” asks Qiu in “A River of Crimson: A Brief Stay in the Glorious Capital.” This is a craving not for a lover, but for something more valuable: a partnered relationship that is more intimate, intense and committed than simple friendship, but without the emotions or expectations associated with romance or sex—what many within the queer and asexual/aromantic community identify as a queer platonic partnership.

Qiu’s words deeply resonated with my own experience from when I first started identifying on the spectrum of asexuality. Seeking relief from loneliness, I tried to kindle new friendships in spaces that too often emphasized intimacy within normative sexuality and romance, leaving me feeling out of place. Those same experiences have been echoed in conversations I’ve had with other asexual, aromantic and bisexual people. Their frustration at being stymied in their efforts to find kindred spirits of their own echoes as I read Qiu’s words: “Socializing in frivolous ways exhausts all my sentiments.” I cannot help but wholeheartedly agree.

"I imagine her words anew, for all of us in the diaspora who share complex or fraught relationships with our mother tongues."

If Qiu Jin’s poetry speaks to the connection between kindred spirits, then Zhang Qiaohui (1978 – ) addresses the relationship we have with language and the idea of a homeland. As a second-generation Filipino immigrant, this is a bond that I struggle with, finding myself in a liminal place between Canadian and Filipino identities.

Zhang’s poems speak to a bond with the land that is linked to our ties with nature and the artifice of our constructions. “When she toils in the fields, she too is like a plant / When she speaks in dialect, she’s also like a deity of the land,” says the poet of her mother in “Dialect.” This earnestness is contrasted to the comforting Buddhist pagoda in “The Pagoda of a Thousand Autumns,” which turns out to be merely a façade, made with modern materials—a “pseudo-classical reconstruction made of bricks and reinforced concrete.”

Like Zhang’s pagoda, the Filipino-Catholic norms and cultural practices I was raised with felt comforting and safe. Even after these ideas were shattered by the experiences and questioning that led me to discover my queerness, I still yearned for the comfort of their familiarity when I found myself, like Zhang, seeking acceptance in a new community. I needed to let go of what I thought of as home. As Zhang tells us, “the ancestral land is a deity / and also, a useless decoration.”

At the end of Zhang’s section is “Remnants,” a poem that brings to mind the tenuous connections I have with both Filipino culture and my own family history. When reading the lines, “Photos, the faded imprints of fleeting light and shadows; / reminiscence, the residue of longings” my mind goes to a brown suitcase below my desk with documents and photographs of my father in his youth. It is my last tangible point of attachment to a personal history where my exploration feels like a walk though structures ruined beyond recognition. Yet, my own work in creative non-fiction has rekindled a passion for Filipino cuisine and food culture—a part of my life I’d always associated with my father’s destructive anger. Among the wreckage, there is still space for new blossoms to grow, tinted with a “light blue, a dwindling trace of tender pain.”

Poems that appear enigmatic at first glance might be communicating in quieter and subtler ways, seeking to be experienced and felt rather than to be unpacked and rationalized.

Next, Wang discusses the poetry of Fei Ming (1901–1967) as being particularly inspired by poets from the Táng Dynasty (618–909), reflected in writing known for embracing elusiveness and ambiguity. In relating the tale of their struggle with translating the piece “lantern,” Wang reflects on the power of what goes unsaid and unexpressed in Fei Ming’s work: “ … a poem is so much more than the words on a page—it’s also the gaps that the poet has left behind.” With its opaque language, “lantern” paints a scene that feels like a movie shot through a diffusion filter—hazy and dreamlike. The line “the lantern light seems to have written a poem” evokes memories of the late-night walks I took in graduate school, where wind-blown leaves cast shadows from street lights, scribbling verses across the pavement.

This opacity is also seen in the poem “floating dust of the mortal realm,” where Fei Ming writes about embracing the transience of the world. Here mountains are ephemeral, and writing is encouraged to fly away as ash. “The nebulous ephemeral world is a speck of the deeply cherishing heart. / the universe is a particle of indestructible dust floating in the air.” These two poems speak to an experience of existence that goes beyond what is easily classified, categorized, or placed into neat little boxes. Like queerness, it just is.

The allure of Fei Ming’s voice also stems from his subversive use of classical Chinese motifs, seen in the piece “nipping flowers,” which uses the imagery of peach blossoms and the moon in unexpected and unfamiliar ways. It defies easy interpretation, evoking a surreal scene where one chases immortality while they also eschew transcendence: “the bright moon rises, hanging in mourning / i’m delighted to see that i’m still a human being.” Upon asking Wang about this poem, I’m told that, among other things, it’s about both wanting and fearing immortality. My own journey into queerness came with the loss of relationships; ascending to a higher state can carry with it a discomforting sting of bitterness. We could be forgiven if that makes us less enthusiastic about swallowing the peach blossom petal.

In “to wander out,” Fei Ming is more explicit in his language, but there is still a beautiful sparseness to how he conveys his experience of loneliness and isolation. When he writes, “shoulders rubbing heels bumping / do not leave just one trace of emptiness,” my mind summons images of disappearing into a crowd, experiencing a thirst for humanity and intimate togetherness while one is drowning in a sea of people. When I started embracing solitude as a queer person, divesting myself of amatonormative and heteronormative ideas about relationships, it brought with it an indescribable spectrum of wonder, detachment, curiosity and sadness all at once. Fei Ming is able to speak so loudly to both his and my experience with what he says and what he doesn’t say.

Claude Debussy famously said that music is in the space that exists between notes. Miles Davis tells us that jazz is in the notes you don’t play. Likewise, the allure and power of Fei Ming’s work comes from what Wang calls the “expansive space that lingers in between and around Fei Ming’s words.” Like music, the power of a poem is in the liminal spaces between words and lines. As alluded to in “lantern,” sometimes the strongest connections we can have are the ones we make with silence.

Although a tree is easily overlooked as a common part of many people’s everyday surroundings, it has the potential to transform into things far more powerful than we might first imagine.

Following Fei Ming’s enigmatic poetry comes Xiao Xi (1974 – ), a poet whose work pushes us to open our eyes to both the mundane beauty and the horror that occurs around us. The first poem, “the infinite possibility of trees,” reminds us how even the most seemingly trivial items in our world can be remade into phenomena both profound and prosaic. Sometimes, Xiao Xi muses, trees can be a box or a pole, and sometimes they can be “a lone qin, its chords shattering the kingdom’s rivers and mountains.”

If trees have such infinite possibilities, how much more do people and their capacity for change and transition? Perhaps queerness can be equally limitless in its paths going forward. For most of my own life, I never thought it was possible to think of myself as a part of the asexual and queer community; what changed was the understanding that asexuality and queerness exist as a spectrum, and how limiting it was to think of my own sexual identity within the narrow and rigid terms and definitions set by others.

A later piece called, “the car is backing up, please pay attention,” commands us to notice the trivial occurrences that happen in our daily lives, for awareness of them is to also witness their significance. Paying attention can take many forms, whether it is toward “the elderly and the hushed trees,” “the light reflected on broken glass,” or the impatient silence of unexploded firecrackers. All are important. Another poem, “the ceaseless wind,” depicts moments of ephemeral sorrow that exhort us not to dwell on their causes, but to simply remember that they exist. “Please let wind return to the wind’s mist, let lightning hide in the sleeves.”

Among Xiao Xi’s poems, “selling sewing needles” is a major highlight of this section and one of the stand-out translations in the book. Here, Xiao Xi juxtaposes the consumerist horror of people “auctioning their kidneys off to pay for iPhones” with a woman selling sewing needles. Maybe it is these needles, presented “slowly, without hurry, with all the sizes large and small,” applied with a desire to mend and repair, that can heal our ruptured selves in ways that excessive consumption, the worship of youth and the fast pursuit of wealth cannot.

Another compelling translation is “between life’s hardships and poetic beauty," which evoked childhood memories of my father’s experiences with hunger. It also brought to mind recent conversations with friends on social media struggling with the socioeconomic and sociopolitical strife besieging queer, racialized and disabled communities today. In these conversations, we made promises to no longer be stuck in accepting things as they are: “when it comes to life’s hardships and poetic beauty / we shall not compromise anymore.” We made promises to treasure even the smallest morsels of nourishment that we can have, to hold on to hope and the drive to keep fighting, like the last grains of rice on a finished plate.

Our fragile silken wings flutter as we take flight together, trailing the voices of the past across pages both familiar and new, guided only by the warm light of a lantern glimmering in the dark.

The final section is devoted to Dai Wangshu (1905–1950), a famed poet of his generation, but like Wang, also a poet-translator. From the 1920s to the 1940s, he worked to bring European poetry and literature, such as the work of Charles Baudelaire, to Chinese audiences. The influence of his exposure to Western writings can be seen in “I Think,” which, as Wang points out, elegantly syncretizes René Descartes’s famous expression, “I think, therefore I am” with Zhuangzi’s parable of the Butterfly Dream. Did we wake from a dream of being a butterfly, or are we part of a butterfly’s dream of being human? Who is doing the thinking and who is doing the existing? Perhaps we are ultimately bound for a place where our thoughts and dreams go beyond such questions. “The gentle call of a tiny flower / shall travel through misty clouds that know nothing of dreams or awakenings.”

“For Jin Kemu” directly references another poet-translator who translated a Western book on astronomy for Chinese readers. Why, Dai asks, is Western science so insistent on naming everything in the cosmos? The planets and stars “wander leisurely in outer space, free and unattached, / not comprehending us nor seeking to win fame.” Of such wonder we are encouraged not to try to process, classify, or categorize such things, but to find the simple joy in noticing them as they are.

The final two poems provide a wonderful coda to the book by looping back to pieces from other poets through imagery and tone. “Autumn Night Reflections” opens with a question about mending, reminiscent of Xiao Xi’s “selling sewing needles” (“Who is sewing with needle and thread? / The heart also needs autumn clothes.”), then turns to a reflection on songs of the heart which evokes Qiu Jin’s “Spontaneous Thoughts” (“the heart is a qin. / Who else knows the archaic songs, / “Bright Spring” and “White Snow?”).

“Night Moths” evokes a nighttime scene of moths “circling the halo of candlelight” that accompanies the night writing of Fei Ming’s “lantern”. Its imagery also calls to mind the ties between ancestors and the land seen in Zhang Qiaohui’s poem “Dialect” when Dai writes, “Moths are said to be napping kinfolk, / soaring across the steep mountains and passes of distant borderlands, / soaring across the far-apart longings of clouds and trees.” In a time of uncertainty and darkness for many, we, too, can see ourselves in the dancing of moths, flashes of colour striving for light.

Poetry isn’t what is lost in translation, but rather, what survives it.

The power of these poems to resonate with a reader like myself across space and time is intertwined with the translator who bridges the gap between poet and audience. That is why the interstitial essays concluding the sections for each of the five poets are so critical. In these essays, Wang effectively grounds readers in the world of each poet, providing important background and historical context. But these craft essays also highlight Wang’s personal relationship with each of these poets through the delicate craft of translation.

Wang’s piece on Qiu Jin is less an essay and more of a heartfelt, time-spanning letter recounting the 2023 incident where the British Museum stole and later erased Wang’s translations of Qiu Jin’s work, triggering an international response which included the formidable fandom around the K-pop group BTS and the asexual and aromantic community. Here, Wang spotlights the continuing effects of white supremacy on translated poetry from marginalized writers: “I can almost hear you sighing,” Wang writes to Qiu, “As I explain that the poetry written by racialized writers of marginalized genders…are triply underrepresented in English translation, simultaneously along the axes of language, race and gender.” It is a reminder of how the struggle to preserve and uplift queer women’s voices in face of erasure and oppression is as important now as it was in Qiu Jin’s time. Qiu’s words still stretch out to those zhīyīn—kindred spirits—who hunger for community and human intimacy.

Wang’s writings on Zhang Qiaohui are an insightful musing into how the act of translation is also an expression of what Wang calls diasporic yearnings. “To savour the rhythm of (Zhang’s) poetry in the Yibīn branch of the Sichuān dialect of my ancestral hometown which I inherited from my grandparents, is a powerful act of intimacy,” Wang tells us. In their discussion of “The Pagoda of a Thousand Autumns,” Wang speaks to how translation is a yearning for home—one compelling them to build a replica of home built from “simple words and hard labour.” While it may be mundane, “unmagical and merely decorative,” the art of interpreting meaning for a new audience is still a source of comfort to those seeking what feels so far away.

The piece devoted to discussing Fei Ming lends a beautiful look into Wang’s journey into the complex and challenging subtlety that comes with translating concepts into English that are elegantly expressed in Chinese. How do we take a concept of positive emptiness and map it onto words in a language where emptiness largely has a negative connotation? A word that can mean “empty” in some situations can also mean what Wang describes as “spacious and airy, a poignant observation about the unfixed, unpredictable and fleeting nature of the world,” which eventually brings us to the word “ephemeral,” as seen in the “floating dust of the mortal realm.” For Wang and Fei Ming, translation becomes more than just a transition into English from Chinese; it is an interpretation into English from the language of liminality.

The essay covering Xiao Xi takes readers further into the challenges of translating Chinese poetry into English. In one illustrative example, Wang takes us through their process of translating a word from the poem “the infinite possibility of trees” that could be literally read as “countless.” However, there are several English concepts and words that could be mapped to that Chinese word, including “limitless” or “endless.” Which of these are the most appropriate in their tone and subtext for communicating the immense range of possibilities that a tree could become? A similar dilemma is laid out before us with the Chinese word that translates to “pay attention to,” used in “the car is backing up, please pay attention.” In addition to being a call for awareness, this word could also be mapped to other situationally specific verbs such as “behold,” “beware,” and “watch out.” Not being able to find one specific English word or phrase which accurately graphs to the Chinese word, Wang instead tells us how they decided to guide the reader through the differing isomeric forms of this word in English, building intensity through meaning. Here, we glimpse how Wang’s careful word choice and construction make these translations as much a reflection of Wang’s own literary sensibilities as it does the poets they translate.

Finally, in their essay on Dai Wangshu, Wang introduces us to a poet-translator whose passion for blending the worlds of Sinophone and Anglophone literature echoes that of Wang in the present day. Here, Wang also shows us how Dai’s poetry explores the bond between the self and the other, exemplified in Dai’s poem “I Think.” Such a bond is not a one-way dialogue but rather a merging of influences from each side of the conversation—a dynamic that also mirrors Wang’s own journey as a translator, as seen throughout the book. Dai also worked in the aftermath of a movement of Sinophone poet-translators who worked in the 1910s and 1920s to bring Western literary works to Chinese readers. Their legacy is one that Wang steps into, continuing the movement’s work and bringing it to new audiences far and wide.

For readers seeking innovative and boundary-pushing poetry and writing that immerses the reader in Chinese and translated works, The Lantern and the Night Moths offers an opportunity to experience verse in communion with poets who—as Wang says in her discussion of Fei Ming—smile at us in quiet understanding, like the Buddha and Mahākāśyapa.

I also personally feel that for queer audiences, The Lantern and the Night Moths is especially affirming and uplifting. This book reminds me I’m not alone in craving heartfelt connections with like-minded souls. In my fight to live authentically as myself, I am part of a long lineage of revolutionaries, lovers, and artists. To have my struggles echoed and experienced by poets who lived decades or centuries removed from me is validating in profound and powerful ways.

Among so many constant reminders of the societal fragmentation all around us, The Lantern and the Night Moths delivers a powerful message: we are not as alone as we might think. In our experience of longing for an other, or of rebellion against what separates us from ourselves, Yilin Wang and the five poets they translate show me that there are those whose spirits resonate with mine despite time and distance.

Whether these spirits exist in the pages of Chinese poetry or on the other end of a Zoom call, may we all come to find our own zhīyīn who cherish the same songs as us.