Vulnerability and Self-Defence: A Review of Aaron Schneider’s What We Think We Know

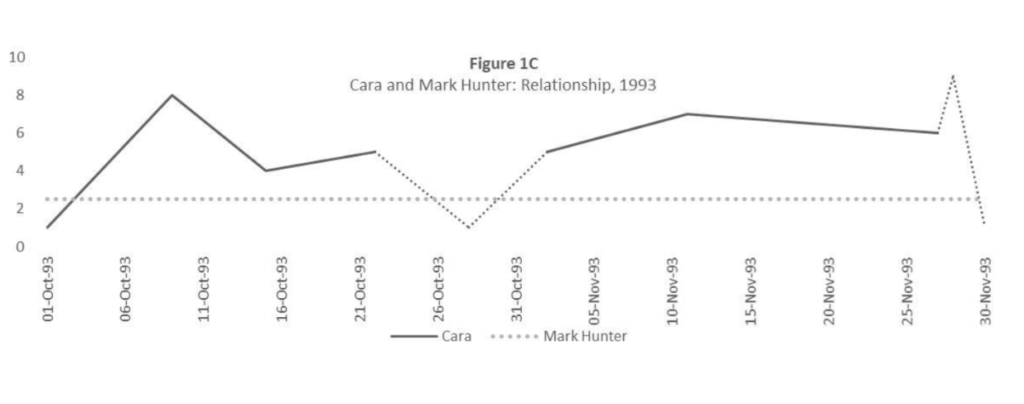

Aaron Schneider’s debut experimental short fiction collection What We Think We Know explores the vulnerability and emotional well-being of its characters through novel rhetorical strategies such as charts, graphs, reports, lists, taxonomies, interviews, observations, and data analysis. In “The Cara Triptych” section, for example, the vulnerability and emotional well-being of Cara during her relationship with Mark Hunter is visually charted in “Appendix C: Happiness and Related Scalars” the third and final story of the triptych. Mark’s constant impact on Cara is offset by Cara’s fluctuating investment in her relationship with Mark, thereby creating a neat visual representation of the narrative arc of her relationship as one with differing motives and differing emotional investment in the relationship when comparing the two characters.

That Cara never reaches “the zero of forgetting” foregrounds the lingering impact of the relationship on Cara, reflecting both her emotional vulnerability and her unwillingness to let go of the past. Schneider contrasts the indisputability of the relationship’s impact on Cara with the ambiguity of Mark’s emotional investment in the relationship. It emphasizes Cara’s emotional vulnerability in the relationship and her inability to effectively shield herself from the pain of a one-sided relationship. It’s a pain that endures, even as successive graphs illustrate later relationships that veer from the neglectful to the awkward, and, finally, to the neat overlapping lines of marital happiness.

It’s worth noting that “Appendix C: Happiness and Related Scalars” functions as an appendix of sorts to the previous two stories: the observational and interview-like “Cara’s Men (As Told to You in Confidence),” and the case study “Sex (With Footnotes).” Together, these pieces attempt to examine Cara’s relationship history as a full-scientific inquiry that includes defining variables such as “most lasting memory” and “reason for ending the relationship” in a cold, scientific language, even as the definitions are meant to explore concepts decidedly emotional and qualitative. The graphs, definitions, narrative observations, and reports in “Cara’s Men (As Told to You in Confidence)” and “Sex (With Footnotes)” illustrate Cara’s emotional journey through her romantic relationships by deploying the tropes of scientific inquiry as story structure. Cara’s feelings and motivations and consciousness remain the focal point throughout the investigations of her relationships even as the quantitative assessments represented by these tropes structure these experiences into a narrative. Schneider foregrounds Cara’s experiences while inviting the reader to question their own interpretative framework in engaging with these short stories, and, by extension, the broader narrative forms of the short story.

Variables such as “most lasting memory” establish qualitative definitions for themselves by describing a state of consciousness that cannot be counted empirically. Cara’s “fleeting impression” remains elusive even to herself, and any interlocutor who attempts to catalogue her lasting memories of former partners as data points wrestles with the intangibility of her conscious thoughts. Such an emphasis on the intangibility of Cara’s conscious thoughts in the reports introduces an indeterminacy into the text that undermines the empirical authority of data collection. The “what” of each memory, and its substitution for Cara’s memories and hopes in each relationship, becomes nostalgic, emotional: “what” could have been, or “what” could be in each relationship, if you will.

“What” is intangible and not subject to empirical study. And if Cara’s thoughts are so fleeting that “she has thought something without knowing precisely what,” the project of collecting and analyzing her thoughts becomes suspect upon its first principles. Much like Poe’s infamous House of Usher, there’s a fissure in the foundations of these studies that threatens to bring the whole project crumbling to its ruin. After all, “what” could be anything, especially in the context of a data set relayed to a third party.

One such third party is the reader, who Schneider often collapses into the text as a participant or interlocutor. “Cara’s Men (As Told to You in Confidence)” uses the second person “you” throughout its narrative, thereby aligning the reader with the protagonist of the story. Schneider’s use of second person heightens the intimacy of Cara’s confidence, even as the narrative introduces questions about the interlocutor's intentions in listening to Cara and whether such confidence is warranted. Confidence, here, suggests a double meaning: both the trust placed in someone for sharing a piece of privileged information, and in the belief that said trust will not be betrayed. Which, of course, leads to a third variation: a confidence trick played upon someone that is dependent upon earning their trust. The interlocuter gains the trust of Cara by listening to these stories as confidence trick for his own ends: both to engage in sex with Cara, and, presumably, to have a story, much like the one being read.

The ambiguity of “Cara’s Men (As Told to You in Confidence)”, therefore, rests in the ambiguity of the interlocutor’s position as an attentive listener and as a future sexual partner, as seen by the end of the story. The interlocutor’s motive, by virtue of the absence of his perspective, remains indeterminate. By placing the reader in the position of the interlocutor, they too are subject to the ambiguity of this position and its indeterminacy.

“Sex (With Footnotes)” chronicles Cara and Sebastian having sex, with, as the title implies, footnotes. Schneider cleverly reflects the feelings of vulnerability that both characters experience during the encounter, with the footnotes, indicating Cara and Sebastian’s thoughts, taking up progressively more and more space on each succeeding page as their self-consciousness grows and observations accumulate, culminating in the beginning of sex. As Cara and Sebastian begin to turn their attention to the physical matter at hand, the footnotes begin to take up less and less space on each succeeding page, suggesting that Cara and Sebastian are feeling less self-conscious and more comfortable with their encounter. Consequently, these inner monologues attempt to shield both characters from the threat of emotional pain that their physical vulnerability exposes to their psyches. Footnotes, in Schneider’s story, become a form of self-defence, protecting and reflecting Cara and Sebastian’s vulnerability.

Which brings us back to the third story in this triptych, “Appendix C: Happiness and Related Scalars,” where the reader encounters the impressive number of reports and graphs that outline the trajectory of Cara’s relationship history. The reader takes on the role of a researcher negotiating the reports and graphs, used both to chart Cara’s relationship history and to construct the narrative of Schneider’s story. The results are summarized on the final page as shrinking and growing circles, with sadness and despair being in an inverse proportion to happiness and fulfillment. But there is no guarantee that these trends will continue, nor even that they should.

But although the Cara triptych is formally unique, most striking in the collection is “107 Missiles: An Autofiction in Fragments,” which navigates the narrator’s determination to master some form of self-defence as a way of masking his own self-conscious vulnerability. After experiencing severe childhood bullying, the narrator demands that his father teach him self-defence. He later becomes dissatisfied with the tripping technique that his father reluctantly teaches him, and attempts to unravel his father’s own methods of self-defence with frequent references to President Reagan’s Strategic Defence Initiative. Following the discussions of self-defence are the stories his father and his father’s friends tell about his father’s life leading the Men’s Group. The narrator compares his father’s career and his lack of prior credentials as akin to an electrician without credentials or experience who went on to have a long career. The narrator doubts these stories, both of his father’s success and how his father came to work there, and asserts that his father uses stories to obfuscate his credentials and avoid criticism:

If I said the same thing to the friends and colleagues gathered together at his retirement party, they would never accept it. They couldn’t deny the basic facts. The BA in Environmental Studies. The books in their outlines of dust. But they would refuse their implications. They are too close. Too close to him. To the narrative of his career. To the three decades of anecdotes they passed back and forth over the plates balanced on their knees. This is how stories work. They are shields to save us from what we don’t want to see. And my father’s story, as his friends and colleagues know and tell it, is perfect from beginning to end. A better bulwark than the Kemble Rock. As simple and impossible as the idea of missile defence.

I must admit, when I first read this story, I didn’t know what to make of it. I couldn’t tell what difference it made if an electrician did or did not have their credentials if the electricity worked and nothing caught fire. Surely, evidence of the latter would be what would raise questions about the former, and everything would fall into place from there? Still, I was thrown off by the references to Reagan’s Strategic Defence Initiative, which I took to be equating the stories shielding the father with Reagan’s proposed missile system shielding the United States.

And then I read the story’s title again.

Dear reader, I submit to you that the 107 missiles of the story’s title are the story fragments that the narrator deploys to defend his own vulnerability in the world. He becomes self-conscious of his own vulnerability through childhood bullying, and projects these same vulnerabilities onto his father when he doesn’t get the solution for self-defence that he wants. Here, the parallel becomes one between the narrator and Reagan: both fear the world because of their vulnerability, and both need a method of fighting back. There is an imagined gun at their heads, and the use of violence isn’t out of the question in the name of defence. Consequently, the narrator’s father becomes a stand in for the narrator, and in the quotation above, I read the pronoun “they” as a stand in for you and me, as the readers of Schneider's story.

“107 Missiles: An Autofiction in Fragments” insists that there is nothing more suggestive of being vulnerable and fearful than trying to be invulnerable and free of fear. In turn, it makes peace with the indeterminacy inherent in such observations while offering up the observer’s observations up for scrutiny by the reader. As a result, consciousness and personal experience are recentered, and the emotions and perspectives that would otherwise remain hidden become known. Schneider’s collection encourages us to accept our vulnerabilities and fears for what they are, and warns against searching for a perfect self-defence mechanism that could never exist in the first place.