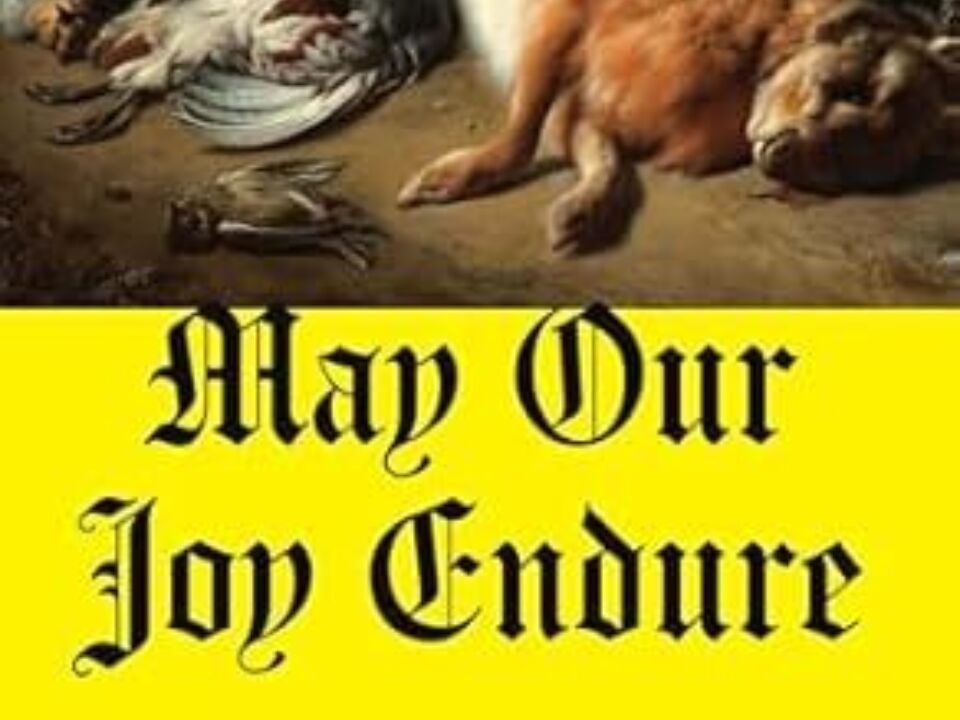

Fragile Lives: A Review of May Our Joy Endure by Kevin Lambert

Every now and then, I find myself longing to read a book with a particular tone, a warm lavishness that absorbs me completely even if the process of reading the book is significantly slowed down. Kevin Lambert’s award-winning novel May Our Joy Endure is such a book, written in a style reminiscent of 19th century realist literature. The novel’s titular phrase is a desperate call, repeated several times throughout the narrative, first spoken as a disillusioned plea in a room full of rich people, as a woman celebrating her birthday whispers the phrase to herself, as if in a trance. Shortly after, an omniscient voice observes:

We all know the gods have been dead far too long for their carcasses to come back to life for us, that all the heavenly angels, wearied and decimated by AIDS, can do nothing more for our ephemeral beings sluiced with Lambruso, yet we implore: ‘Oh may our joy endure.’

Over the course of the novel, the phrase comes to signal a genre of individual stubbornness that has become a dangerous kind of denial, in which self-forgiveness and healing are a guise for perpetuating social inequality and harm.

At its core, Lambert’s story is simple and pertinent. The reader is introduced to Céline Wachowski, a star architect who has designed buildings for the biggest cities in the world and is the founder of the internationally successful firm Ateliers C/W. Céline is the kind of woman who easily brings to mind other fictional characters like Miranda Priestly (played by Meryl Streep in The Devil Wears Prada), a fitting analogy given that Streep is one of the many celebrities whom Céline is said to know, have worked for, and become friends with. Céline’s downfall comes after she wins the bid to design the Montréal branch of the international e-commerce platform Webuy, the design for which, in a classic example of a cosmically endowed genius, Céline sees in “profile in a cup of tea.” Despite the initial buzz and positive publicity, Céline becomes implicated in a scandal one month prior to the project’s completion. The catalyst is an accusatory two-part article published in The New Yorker that frames Céline’s work as gentrification, illustrating how architectural ideals and familiar claims about creating new job opportunities are often grounded in individual greed. Distraught and eventually forced to step down as CEO of her own company, Céline submerges into a lengthy period of self-reflection and aggressive self-defence in which she frames herself as a multi-level victim.

Equally admirable is the way in which Lambert touches on relevant, and often sensitive, topics such as freedom of speech, wealth and class disparity, gender and racial identity, and the lack of respect afforded to the older generation.

A work of translation set in Montréal, May Our Joy Endure is shaped by a variety of literary styles that lend the narrative its compelling quality. It is fitting that Céline becomes obsessed with Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time as Lambert’s own writing is highly literary, forcing a slower, more contemplative reading experience. We are introduced to Céline in medias res, at the 60th birthday party of her longtime friend, Dina. Over the next few pages, we meet a few other key characters: Dina’s husband, Cai; Céline’s colleague, Pierre-Moïse; and Gabriela, a young associate at Ateliers C/W. In this first section, Lambert’s writing is a torrent, as a single sentence can run for most of a page, with only commas to signal moments where perspectives shift. The first piece of dialogue, which appears 48 pages in, is almost jarring in its interruption of what preceded, as Céline tells a group of guests: “My companies have gone from being an enlightened despotism to a democracy of idiots.” The entire section has a touch of Edgar Allen Poe to it, specifically his story “The Masque of the Red Death.” Although Lambert makes reference to the COVID-19 pandemic, what looms outside of Dina’s apartment in this first part is not a personification of death but rather a reality of social and economic precarity that Céline refuses to see.

The writing style changes in part two, breaking down into smaller sections that emphasize narrative as the Webuy project is approved, then challenged, then halted entirely. Here, the reader focuses on Céline and her work as an architect. Part three is both the lengthiest and most stylistically wide-ranging, shifting in focus from Pierre-Moïse and his partner, Nathan, to Céline’s reminiscence of her childhood. Fittingly, the penultimate narrative development is Céline’s 70th birthday party which, hosted in Dina’s home, serves as a foil to the opening event. Although Céline remains the focus of attention, the mood has become sullen, with the dinner table becoming a space of tension and social breakdown on a microcosmic scale; Céline announces, at one point: “The problem is that we’re always timid in Québec, we apologize for living and ask people politely not to step on our feet as we haul our legs along the road.”

Equally admirable is the way in which Lambert touches on relevant, and often sensitive, topics such as freedom of speech, wealth and class disparity, gender and racial identity, and the lack of respect afforded to the older generation. Often presented as debates or loud and direct assertions, these passages take on a hyperreal quality, as if Lambert’s goal was to see what it would take to get the reader to talk back to the book. The reception of The New Yorker exposé is a case in point. Michel, Céline’s assistant, describes the journalist who wrote the piece as “a typical hipster in her 30s … a New Yorker playing at being pauperized and cool, who took photos of her lattes and posed in her pyjamas in front of her webcam, along with her cats.” Lambert speaks to the tendency of some members of the older generation to dismiss the valid concerns of the younger as proof of a search for dirt, an instance of wrongdoing that can be used to build a case for writing off, or “cancelling,” a person. Unsurprisingly, Michel is one of the loudest, most troubling voices at the dinner table, convinced that a radical left is encroaching on what he considers the traditional and level-headed values that have survived for so long in Québec.

A more positive example of Lambert’s engagement with timely topics is Pierre-Moïse’s contemplation of his commission to design the Afro-Descendants History Museum of Canada, a tongue-in-cheek reference to projects like the Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery at NSCAD University in Halifax, the existence of which was put into flux in 2022 after its founder and director, Dr. Charmaine Nelson, left the organization, citing her experience of racism. Pierre-Moïse questions the sense of fulfilment this commission gave him and considers distancing himself from Céline, “recklessly modifying the parameters of what his profession means, questioning himself on the legitimacy of buildings he himself designed in the past,” and asking “what’s a museum worth if it ruins poor families’ lives, the lives of undocumented immigrants.”

These individual instances are set against a backdrop of systematic failure as Lambert describes “the forgotten ones”:

People who had not been able to navigate the market’s snares, who had visited many apartments without being selected because they had failed their credit check or because their name, which didn’t sound French or English, was anathema to the owners.

The “poster” character for this systemic failure is a man named Greg, who commits suicide after being forced to close his small restaurant and losing his wife to cancer. Greg exists as a vague spectre of suffering, his name mentioned more as a symbol of tragedy rather than as an entry point into a complex individual. His continued presence in the text exists only through the thoughts and words of those significantly more privileged than himself, people like Céline, who mention him less with empathy than with a degree of surprise, as if being reminded of the true extent of hardship that exists in Montréal and Québec more broadly.

Lambert imbues the writing with a sense of joy that has been rediscovered and which exists in silence, in stolen moments of peace and rest that allow for the contemplation of artworks that are out of reach for characters like Amalia.

Another character who appears like a spectre is Amalia, a cleaner who enters the novel near its end, following a violent break-in during Céline’s party. In Amalia’s lengthy internal thoughts, the only ones to truly match Céline’s in style and complexity, she reflects on abandoning her master’s degree in art history as a missed opportunity to be successful in the art world. Observing the predictable abstract artwork that lies damaged around the home, Amalia recalls her admiration for Pieter Bruegel the Elder and the excellent undergraduate paper she wrote on the artist which compelled her professor to encourage her pursuit of a graduate degree. Amalia is convinced that if she were as rich as Céline, she would have better taste as well as more humility about spending the money. She longs to be surrounded by art but lacks the same access as Céline and her social circle.

The warmth and slowness of the opening section returns once again in this brief encounter with Amalia. Lambert imbues the writing with a sense of joy that has been rediscovered and which exists in silence, in stolen moments of peace and rest that allow for the contemplation of artworks that are out of reach for characters like Amalia. It is in these few pages near the end of the book that the phrase “may our joy endure” acquires another meaning. Amalia is a reminder of the multitude of other people that exist around figures like Céline, their joy restricted to moments of escape that are no longer truly their own, as they are being wrested from a system that encourages work and a dream of consumption-based success.