Echolocations

“I long for an essay form that brings together many possibilities … I would love for a book of essays to be a fold-out book or a pop-up book or an accordion book, something that would be altogether different in shape and form, which would drive a more experimental thinking … Form allows for expansion through a kind of multi-dimensionality.”

—Anne Simpson

“When I read the poems in the collection [Murmurations] now, I can feel the speaker discovering and re-discovering things—love, the world around her, her beloved, and herself—over and over through the poems. What the book centres is less a satisfying sense of resolution or ending than the process of being and thinking through connection with another person.”

—Annick MacAskill

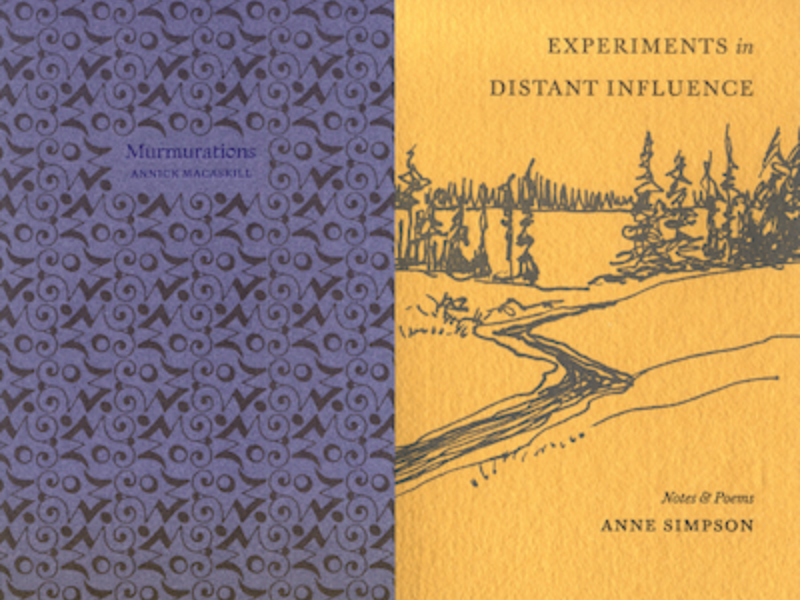

In late September 2020, Nova Scotia-based authors Anne Simpson and Annick MacAskill met up at the University of King’s College in Halifax to discuss their new books Experiments in Distant Influence: Notes and Poems and Murmurations, both of which had come out earlier that year with Gaspereau Press. They decided to continue the conversation over the months that followed, asking each other questions about these collections and their respective writing practices.

Annick MacAskill: Why a book of essays and poems? And why now, for this book in particular?

Anne Simpson: Essays allow me to think about ideas in different ways than I can when I’m working on a poem, or a manuscript of poems, or a novel. I love the way that a nearly hidden idea operates in a poem, or the way a problem or moral dilemma might be at the heart of a novel, but essays go off into the unknown like lunar rovers. They are “assays”: they let me delve into questions that I’m not sure I can answer. And they are malleable, almost stretchy. For me, they also have a relationship to collage: I like to stick different shapes and colours together. I feel as though I can do anything with this form. I can consider friendship, or I can look closely at the ending of the Iliad, or I can talk about a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis in terms of discoveries made by a Spanish neuroscientist in the late nineteenth century. Experiments in Distant Influence developed over a period of ten years when I was also working on a novel. I wanted to write essays with a broad range, though each of them touches, in some way, on the idea of community.

I love the way that a nearly hidden idea operates in a poem, or the way a problem or moral dilemma might be at the heart of a novel, but essays go off into the unknown like lunar rovers.

AM: Your title includes a turn of phrase that appears almost antithetical—“distant influence”—though in reading your book, I quickly felt like I had a sense of what you meant by these words. I wonder if you can speak a bit about what “distant influence” is, for you?

AS: That idea of distant influence came from my friend, the poet Tonja Gunvaldsen Klaassen, who suggested that we try writing at the same time each day for a while. But there’s another kind of distant influence, of course. We have an ongoing conversation with writing that has come before us, and it’s a living conversation, even if the writers are long gone. In one of my essays—“Bee Work”—this sort of conversation is intertwined with the words of philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, poet Jo Shapcott, and biologist Jakob von Uexküll. Jo Shapcott is still very much alive, but not the others. I found myself wishing, in particular, that Maurice Merleau-Ponty had lived longer. And I found I really wanted to have a conversation with Jo Shapcott. We are always being distantly influenced, though this has more resonance during a pandemic.

AM: Definitely. And on that note, I’ve been wondering—collaboration and artistic community are obviously very important to you, and this is something that comes out in your essays. There’s your exchange with fellow Nova Scotian poet Tonja Gunvaldsen Klassen, but you also work with other poets, as well as visual artists. Has collaboration remained part of your practice under the pandemic? If so, has the nature of this collaboration changed?

AS: I think I’m interested in collaboration because I work alone so much, as is the case for most writers. I collaborated with John Berridge, who was a photographer, because he asked me to do an exhibit with him on two occasions. I was on the responding end of a call-and-response. In these collaborations, John went first, after completing his work, which was a series of abstract photographs of glass. I had to figure out how to connect and yet simultaneously write something that was independent of what he had done. With Tonja, it was a back-and-forth, a conversation, maybe because there was no pressure to have an exhibit or a publication. Her ideas, her way of thinking, is so important to me. Conversation with other writers, a kind of collaboration in itself, has been necessary for all of us this past year.

AM: I was quite moved by your essay “Tree, No Tree,” which considers, among other things, Susan McCaslin’s Han Shan Project, an important example of ecoactivism through poetry. In this context, you describe poetry as at once useless yet “powerful.” I wonder if you can expand on this?

AS: Auden says this in his poem, “In Memory of W. B. Yeats.” Poetry “makes nothing happen: it survives.” But a little later in the poem, he says that poetry survives “as a way of happening, a mouth.” Poetry speaks, and it can speak on behalf of that which can’t speak—trees. I think that the Han Shan Project had impact because the poets were offering a kind of witness, through their poems, on behalf of the forest in Langley, B.C. It was a moment of ecoactivism, you’re right, and it was an instance in which poetry did help to change minds. That land in Langley was purchased by someone who had gone there for picnics when she was a young woman, and she saved it from development. It was a minor victory, but it gave me hope, as a writer. Poetry is both useless, in the sense of not being “of use,” yet powerful in the sense of making a difference in people’s thinking.

AS: Tell me how this book, Murmurations, arrived for you? When did you know it was emerging as a book?

AM: I was about three poems in when I realized I was writing towards a full-length book. The first poem I drafted, “Banff,” emerged over a few days, two or three lines at a time. I didn’t know these lines were connected until they were all there; at the risk of sounding mystical, it was like the words found a shape by themselves. Then I started a couple more poems (one of which never made it into the collection), and while considering these three pieces, I could see the conversation, or at least the threads of the conversation, that I wanted to have with myself, about love, meaning, resonance, and song. I wrote the rest from there, completing a first draft in a year.

AS: In the poem, “Banff,” you have a line: “I say brother, but that’s not what I mean.” And in the epigraph at the beginning, you quote Don McKay: ‘“apt’ names touch but a tiny portion of a creature, place, or thing.” Could you say a little about language and naming?

AM: I found that Don McKay quote, which comes from his essay collection Vis à Vis: Field Notes on Poetry and Wilderness, after I finished a first draft of Murmurations. McKay articulates—and so well—part of what I tried to do in this collection, which is gesture towards the limits of our language. We name, I think, in an effort to understand and decode the word for ourselves. Poets in particular practice this incredibly attentive art of observing and naming with human language, while also acknowledging the existence of the ineffable, of that which cannot be spoken. Or, you know, to share McKay’s more elegant assessment: “Poetry comes about because language is not able to represent raw experience, yet it must.” One of the threads in the conversation that became Murmurations was an extended interrogation about these efforts to represent, to communicate, while also seeing where human language fails. From there, the book opened up to a consideration of other kinds of communication, representation, and meaning, like bird song and other sounds of the “natural” world.

We name, I think, in an effort to understand and decode the word for ourselves. Poets in particular practice this incredibly attentive art of observing and naming with human language, while also acknowledging the existence of the ineffable, of that which cannot be spoken.

AS: There is such intimacy, such tenderness in these poems, and at times an edge, a tension, and at other times a withholding, the not saying of the thing that’s tucked away. You’re writing love poems … Did that come easily to you?

AM: There was a certain ease that came with writing this book because I was inspired, both by my own experience, as well as by the tradition of love poetry, which has long fascinated me. I had tried writing love poetry before with much less success, but I imagine that work helped me pave the way for Murmurations. As is so often the case with writing poetry, those discarded poems had a purpose, even if they will never be published themselves.

AS: I love the appearance, almost on the sidelines, of Sappho. I think my favourite poem is “Of Gold Arms, You,” which takes its title from a line of Sappho’s, as translated by Anne Carson. Could you talk about the women writers who have influenced you?

AM: There are so many! In writing this book, I was inspired by many women and queer authors who have written love and erotic poetry. Sappho is a major inspiration, certainly, but I think also of women like Louise Labé, a sixteenth-century French poet who wrote romantic and erotic sonnets and elegies. Quite famously, she was condemned by the Protestant reformer John Calvin as a plebeia meretrix (a “common whore”) for having written frankly about love and sex. Labé’s case, like Sappho’s (there is a long tradition of male poets re-writing or mistranslating Sappho to represent her as heterosexual), remind me of what’s at stake for me as a queer woman writer. More contemporary influences for this book include women writers like Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, Carol Ann Duffy, and Arleen Paré.

A common element that these women offer me is an awareness of the body, and an openness towards the beloved that I don’t find in canonical love poetry written by men. As a feminist and queer writer, I feel a responsibility to pay attention to the ways I depict relationships, especially such intimate ones. It’s not just a question of sliding into the traditionally male position of the lover, but of re-imagining the paradigm for a love relationship (and love poetry) entirely.

As a feminist and queer writer, I feel a responsibility to pay attention to the ways I depict relationships, especially such intimate ones.

AM: Coming back to you, Anne, I wanted to ask about your approach to form in your essays, and maybe some of your own influences in this genre. I admire the formal innovation in your poetry, and so it wasn’t a surprise for me that you play with form in your essays as well. I wonder, do you have any favourite essayists, particularly ones who may have influenced your approach to form?

AS: I go back repeatedly to Jane Hirshfield’s Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry and Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet: An Essay. And Mary Ruefle is a poet essayist who opens up worlds for me in Madness, Rack and Honey: Collected Lectures. But it’s not always books of essays that help me to think about form differently: it might be an art book or a diary that reveals how an essay might be explored. I love the wonderful accordion books that my mother bought in Japan long ago, or Sara Midda’s South of France: A Book of Days, which is full of drawings and observations about France, or Jen Bervin’s Silk Poems, a book that combines technology, textile, and poetry, or any of the art books and diaries by Louise Bourgeois. I long for an essay form that brings together many possibilities. These become limitless when I reflect on all that Bourgeois was able to do; she is seen as an artist, but she was also a thinker. I would love for a book of essays to be a fold-out book or a pop-up book or an accordion book, something that would be altogether different in shape and form, which would drive a more experimental thinking. Content changes because of form, but it’s also true the other way around. Honestly, I could not think about writing without thinking about form. Form allows for expansion through a kind of multi-dimensionality.

Content changes because of form, but it’s also true the other way around. Honestly, I could not think about writing without thinking about form.

AM: On the topic of form, can you tell me more about what you’re doing with the essay “Tree, No Tree”? At the end of the piece, you have a series of fragmented paragraphs (I found myself thinking of them as poems), where you appear to have erased text and left blank spaces. Did you start with full paragraphs here? What happened to that discarded text?

AS: I wanted to denude the essay, take the words out. I think most writers try versions of erasure. These sentences at the end of “Tree, No Tree” all made sense at one point, but it was much more interesting when there were just fragments of those sentences, like the detritus left in a clearcut. Whatever forests “mean,” in terms of trees growing together, may be close to what humans “mean” when we put words together. That discarded text was gone, or so I thought, because I’d changed the font colour to white. It was still there, and I realized that the editor had highlighted that text so she could see what I was taking out: the “absent” text. I was quite prepared to lose that text entirely, but I found it ghosting through that particular draft.

AS: I want to ask you about form, too. In “Piano, Piano,” there’s a sense of falling through space. The words, and the music that we’re called to hear—all of it seems weightless. Were you aiming for this in the form of the poem?

AM: I like the word “weightless”—thank you. I certainly wanted to communicate a kind of buoyant movement in this piece. Its form is very directly inspired by a few of Arleen Paré’s poems. In several of her collections she’s written pieces that look almost like traditional prose poems (no broken end lines), but what’s less standard about them is their use of blank space within lines and their lack of punctuation. In Paré’s collection The Girls With Stone Faces, a book that considers the shared lives of Canadian sculptors (and partners) Frances Loring and Florence Wyle, this form is used for romantic and erotic poetry. I found myself quite swept up in the flow, in the energy of these poems, so wanted to try the form for myself.

AS: And tell me about form in “Missed Call.” I love the slight changes in the line that is repeated at the end.

AM: I owe that formal detail to Madhur Anand and to a happy accident. Madhur kindly asked me to submit some work for consideration when she took on her role as poetry editor with Canadian Notes & Queries. “Missed Call” was the poem she liked the most, but she had some suggestions for the line “but her notes envelop / my mind’s soft eye”. I played around with the poem, re-working this phrasing, and sent her back a working draft with a new formulation, as well as alternate phrasings signalled at the end with asterisks and square brackets. She suggested the poem be published just like that, and so it was. In the book, I kept the form because I liked the echo effect it leant to the piece.

AM: Now I’m really thinking about the question of influence! We’ve just talked a fair bit about influence in terms of writing and form, but more broadly, I think of your essay “The Fourth Floor: Notes on Fragility & Courage,” which centres around your friendship and collaboration with photographer John Berridge, who influenced you in another way. You mentioned your work together earlier on, but another topic you touch on in your essay is John’s illness and death, as he was receiving palliative care while you were preparing a poetic component for his final exhibit. You realize something about courage while spending this time with him, sharing that courage can be an act of “stand[ing] within our vulnerability” (175). Can you talk a bit more about your work with John, and about what fragility, vulnerability, and courage mean to you?

AS: John was at his most fragile when he was dying, but in some ways, he was at his most strong. He was prickly, funny, thoughtful. He was afraid. He focused on preparing for an exhibit that he thought he might not live to see. Maybe this became his fulcrum, his support for the teeter-tottering of his days. What struck me was how he was both vulnerable and strong as he faced his death. Courage might be seen as the flip side of fear: the most courageous person might also be the most fearful. I think courage also allows us to escape the burden of the self in some way, in the sense that the truly courageous person is not thinking, “Oh, how courageous I am!” Courage surpasses us. I’m sure John didn’t see himself as courageous in the way he met his death, but I did.

AM: Vulnerability (and courage) are also at the heart of the last essay in the collection, “Palaces of the Brain: Notes on Strangeness & Possibility,” which you wrote about your daughter’s diagnosis with multiple sclerosis. Can you tell me about this piece?

AS: To write this essay, I had to go deep into my own fears. This is perhaps the most personal essay I’ve ever written, and what helped me write it was my obsession with the drawings of the brain by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, considered the founder of neuroscience. I could go back and forth between what Cajal was discovering in the late nineteenth century to what was going on with my own daughter’s brain. It deepened my understanding of the brain, and what might go wrong with the workings of the brain, as in multiple sclerosis. And yet there are places a parent can’t go; I could not be the one to take Sarah’s illness from her. But I learned that hope—“the thing with feathers,” as Emily Dickinson says—was what we needed.

To write this essay, I had to go deep into my own fears. This is perhaps the most personal essay I’ve ever written, and what helped me write it was my obsession with the drawings of the brain by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, considered the founder of neuroscience.

AM: I can see how this would be a particularly vulnerable piece for you. Your phrasing about courage that I quoted above (“stand[ing] within our vulnerability”) made me think of the act of writing and publishing personal essays, or really any kind of writing at all. Do you think about writing as an inherently vulnerable act?

AS: Yes. What we choose to do—writing—is always an act of courage. It takes courage for all writers, but I think it takes tremendous courage to write, even now, from the standpoint of being women. Adrienne Rich says we need to resist “the forces in society which say that women should be nice [and] play safe … [and] insist on a life of meaningful work, insist that work be as meaningful as love and friendship in our lives. It means, therefore, the courage to be ‘different’…” The kind of courage that Rich speaks of has to be sustained however our writing is seen by the world, whether it is judged as domestic or political, whether it is disregarded by the world or given high regard by the world. Our speaking out, as women writers, does involve vulnerability, and yet it is all the more necessary to speak from this standpoint.

AS: Let me ask you about something that struck me in your book. Many of the titles in Murmurations mark places on a kind of map of the heart, as you move steadily east across the country from “Neville Park,” “Queen Street East (Matins),” to “Martinique Beach,” or “Inverness County.” Could you talk about place and its importance for you in this book?

AM: In writing a book of love poetry, I wanted to capture the sense of newness and awe that comes with falling in love. It’s cliché, but I think the world truly does feel new when you’re in love. You feel awake in a different way, and maybe pay more attention to your surroundings. This sort of wonder and admiration—before the beloved, but also before the world itself—is something I wanted to recreate in the book. I wanted to communicate the kind of intense sensual and sensory experience of falling in love, and paying attention to the spaces I inhabited and representing their texture in my poetry was part of that.

In writing a book of love poetry, I wanted to capture the sense of newness and awe that comes with falling in love.

AS: Birds fly through so many of these poems. Tell me about how they inform this book.

AM: The double definition of “murmuration” was a guiding focus as I wrote the poems in this collection; the word means both a murmuring sound and a flock of starlings. As I mentioned earlier in this conversation, birds served as a kind of touchstone in my exploration of sound, language, meaning, and song. And in looking to communicate what I was just talking about—the speaker’s awe before her surroundings—birds were a very obvious presence; of all the non-domestic, non-human animals in our environments, they’re the most noticeable. Describing the magpies in the Rockies, the geese in southwestern Ontario, the gulls along the ocean, and the oh-so-many starlings in Halifax, became a central focus for the collection.

AS: And they see the world from above. Was that part of your fascination with them?

AM: Oh wow. No, no it wasn’t, and now that you ask this I’m very surprised I didn’t think of it before. Although, perhaps less directly, I did think of it, or it was a feeling I had in the back of my mind, a sense I didn’t bother dwelling on, a sense of being at the edges of the regular human world, a bit off to the side maybe. When I read the poems in the collection now, I can feel the speaker discovering and re-discovering things—love, the world around her, her beloved, and herself—over and over through the poems. What the book centres is less a satisfying sense of resolution or ending than the process of being and thinking through connection with another person.