Outside the Trauma

The cover of The Outside Circle by Patti LaBoucane-Benson and Kelly Mellings

The cover of The Outside Circle by Patti LaBoucane-Benson and Kelly MellingsThe Outside Circle (Anansi, 2015) tells the story of Pete, a young Aboriginal man who is incarcerated after a violent incident. Soon, he begins a process of rehabilitation at the “In Search of Your Warrior” program at the Stan Daniels Healing Centre near Edmonton, Alberta. The experience leads him to re-examine his choices in light of family trauma reaching back generations.

Patti LaBoucane-Benson is a Métis woman and the Director of Research, Training, and Communication at Native Counseling Services of Alberta. Her doctoral research focused on historical trauma healing programs for Aboriginal offenders. Kelly Mellings is an award winning art director and illustrator. He is co-owner of the Alberta-based illustration, animation, and design firm Pulp Studios.

Julienne Isaacs: Patti, The Outside Circle deals with some heavy themes: gang violence, addiction and incarceration, and ultimately healing. Why did you choose the graphic novel medium to tell the story of Pete’s journey at the “In Search of Your Warrior” correctional program? In what ways does the graphic novel format serve the story better than more “traditional” media?

Patti LaBoucane-Benson: The graphic novel allowed us to use visual metaphors for concepts in the story that are difficult to relay, yet profoundly important in the character’s transformation. The format also allows the reader, in about an hour and a half, to experience the entire healing journey, to feel the full impact of the story in one sitting.

JI: Kelly, I read in an interview with the CBC that you immersed yourself in First Nations culture and toured a residential school prior to illustrating The Outside Circle. How long did it take for you to develop the images in this book? Which passages of Patti’s narrative were most challenging for you to illustrate? Which are you most proud of?

Kelly Mellings: Most of my research was in person and most of my learning and preparation came through sharing experiences, listening to stories, and building new relationships. The one-on-one sharing with people provided a learning experience that informed all of my decisions when illustrating.

Survivors took me on a tour of the residential school, shared their stories, and provided verbal re-enactments as we toured, which gave me a better understanding of what happened in those schools and the toll they took on real people—and how that trauma could create shockwaves for generations.

Touring the Stan Daniels Rehabilitation Centre gave me an idea of how men like Pete lived while on their journey, and an idea of how he would feel in those circumstances. Witnessing warrior grads proudly receiving their Eagle feathers, and then speaking to them, helped me to understand how these hardened men could change and learn grace and kindness.

I was blessed to spend time up north assisting with a documentary that dealt with lateral violence. I spent some time with First Nations youth, listening to the students propose solutions to the lateral violence problem, teaching art, and making some positive artwork to combat the problem.

I was honoured to participate in a sweat, smudge, share a pipe, and join in feasting. These particular experiences helped me understand the importance of illustrating these points, as well as the intricacies and subtleties that make up the rituals.

I feel incredibly fortunate to have had these experiences and they have shaped my artwork, and informed me as a Canadian about our difficult history and what life is like outside of my small circle. I feel like most moments in the book come from a place of truth because of these experiences.

JI: How did you structure your collaboration? How much involvement did you have with Kelly’s artistic choices, Patti—and Kelly, were there any edits to the text to accommodate the design?

KM: Patti had a script laid out, with many of the artistic decisions made.

The best comparison would be a movie or a play script. Everything is there, and you can get the story from that script, but the director and actors can either elevate or weaken the story. In graphic novels, the artist is like a director, actor and cinematographer—there to make sure that the vision remains true to the author’s intention.

I’m hoping that I, at the least, did no harm, and at the best, helped elevate certain moments with my pacing, layout and acting choices for the illustrations.

I was allowed and trusted with the freedom to tweak things if I felt I could bring out the message in a clearer or more powerful way. The sweat lodge scene was scripted out and described, but after Patti and I talked about what Pete is going through in that moment, and how many men feel in his situation, Patti allowed me to add a double-page splash of Pete alone, in the dark, in pain. Collaboration and trust like that elevate the emotional pull of the story.

JI: For me, the most profound passages in The Outside Circle centred on masks. Pete wears two masks in the book, an angry mask that drops over his face in moments of pain or violence—and later, a beautiful mask that expresses his newfound identity as a warrior and protector of the community. Patti, can you talk about the significance of these masks from a psychological standpoint?

PLB: The transformation of the mask is one way that we were able to help the reader understand Pete’s spiritual healing process, which had a profound effect on his concept of role and identity. He begins the story as a rageful, disconnected man who exerts power and control over people he perceives to be weaker. He transforms into a man who sees himself as a protector and provider, who can make good decisions for himself. The mask was a powerful tool in telling this story.

JI: Kelly, can you talk about the masks from an artistic standpoint? What are your artistic references for Pete’s masks and the other key symbols in the story—the bear, or the community circles?

KM: Pete’s mask of rage was loosely inspired visually by various traditional First Nations masks, but was created from scratch. We went through dozens of iterations to get something that felt slightly connected to Pete’s historical roots, but was twisted and naive, having more influence from his gang than his heritage.

Patti had the mask’s expression firmly in mind—she wanted a seething anger, but not a screaming or yelling face. I feel like we landed on something that exactly hits the emotional feeling we wanted. I had some more aggressive versions with open mouths and scary teeth that could have given the wrong feeling or perhaps taken the reader out of those emotional moments.

Pete’s true mask—the bear mask—and the other warrior masks that are portrayed were influenced by the masks that were created by actual Warrior program grads. The masks in the book have the same sense of connectedness and individuality that I saw in those masks. There is a confidence in who they are, and even though it’s a small moment, I wanted that to come through with each of them.

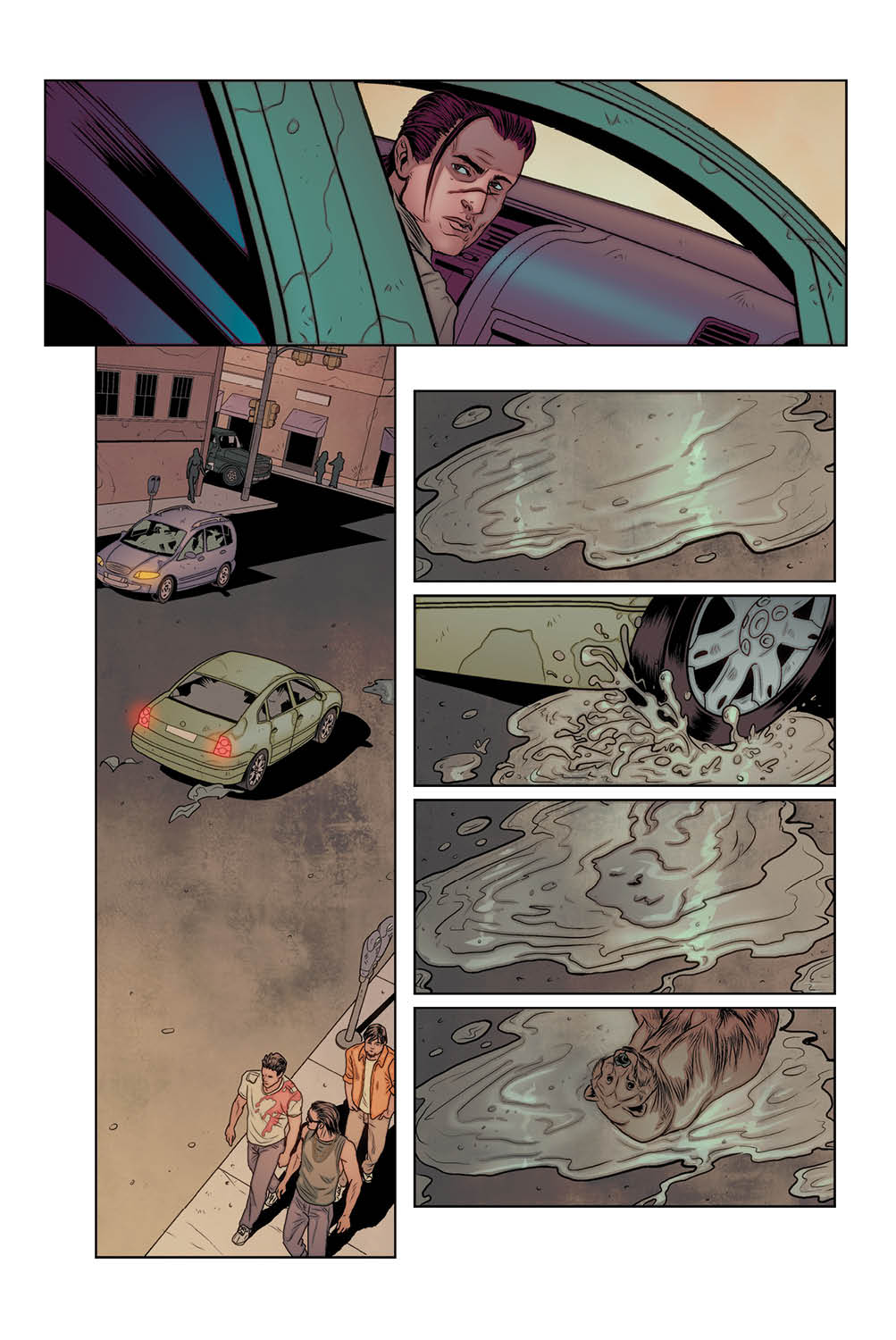

The symbolism of circles, and using the bear, smoke, and masks, all came from the script. Patti gave me the liberty to push things and add or change a few of the instances to help punctuate the theme. The reflection of Pete’s mask in the police car’s hood as he is arrested and the last appearance of the bear in the reflection of the water puddle (echoing and reversing the second page where we see the dirty needle in the puddle) are examples where I was given liberty to push the metaphors and message.

JI: Has The Outside Circle found its way into rehabilitation settings? Do you see it as a potential tool for healing among Aboriginal groups, particularly incarcerated Aboriginal men?

PLB: The Outside Circle is in its third printing in less than a year! It’s being used as a textbook in high schools and universities, as well as for youth who are in a variety of programs across Canada. It is very rewarding to know that Pete’s story is being embraced by service providers as a tool that helps them to help their clients.

JI: The artwork in The Outside Circle amplifies visceral and intensely physical moments in the narrative. What are your thoughts on the power of graphic imagery to heighten the emotional impact of storytelling? In your view, what role should graphic novels play in Canadian literary culture?

PLB: I think graphic novels can be a great addition to the Canadian literary canon. They can be used to tell important stories in a way that may appeal to both the conventional reader as well as individuals who may not consider themselves “readers” and may not be interested in typical novels.

KM: Canadian literary graphic novels are just starting to reach the general public’s awareness. Most new readers I’ve encountered have been pleasantly surprised at the impact and depth achievable.

I tried to leverage the advantage of the graphic medium in telling Patti’s story. We can deal with metaphor and integrate text into images in powerful ways.

Additionally, even the way we lay out pages and structure things can help to heighten the emotional impact and elevate the narrative. The book starts with dark/closed-in panels that were easy to read. This reflects the dark that surrounds and clouds our character at the beginning and subconsciously speaks to the mood of the book.

When Pete makes his first positive decision, the gutters in the book become white—a subtle change, but one that helps punctuate the fact that he is starting down a good path. We also start opening things up, pulling in more warm colours and breaking the panel borders (having some characters or objects go outside of the little square lines surrounding each image).

When we want to slow down time we can add panels; to create tension or show conflict we can crash panels into each other, tilt them, shatter them, or create the borders from a character’s tears. These are tools that are not achievable in any other storytelling medium, and a great writer and artist can use them to their story’s advantage.

Words and pictures combined bring a different power and meaning then other mediums, and are one of the most effective ways of retaining knowledge. This is a big reason why infographics have taken hold of the collective conscience and graphic novels are being used in training and instructional situations. I think that it’s still an untapped medium, with only a handful of literary works among a sea of superhero-sameness.

Julienne Isaacs is a Winnipeg writer. Her reviews and interviews have appeared in The Globe & Mail, Full Stop, and The Humber Literary Review. She is an editor at The Winnipeg Review and a staff writer for The Puritan.