On Inheritance: Hospitality or Decolonial Eating

What we might inherit is not always known in advance of the inheritance. When the inheritance is outside of the material or the tangible, sometimes noticing it is difficult. Part of coming to terms with ephemeral inheritances is being able to notice them and to reconcile them as inheritances. I have been reflecting on inheritance and kinship in my quiet moments for some time now. Recently, I hosted a lunch for a group of friends. We ate tuna crudo with caviar and sea asparagus; scallop ceviche topped with a salad of shaved fennel, fresh herbs and thinly sliced sweet peppers all topped with salmon roe; confit duck legs glazed in orange sauce; green bean and shiitake mushroom salad with orange vinaigrette; fingerling potatoes topped with onions caramelized in duck fat; dessert and copious amounts of wine. It was a celebration of life. We spoke of art, literature, politics, history—we laughed, disagreed, and maybe even gossiped.

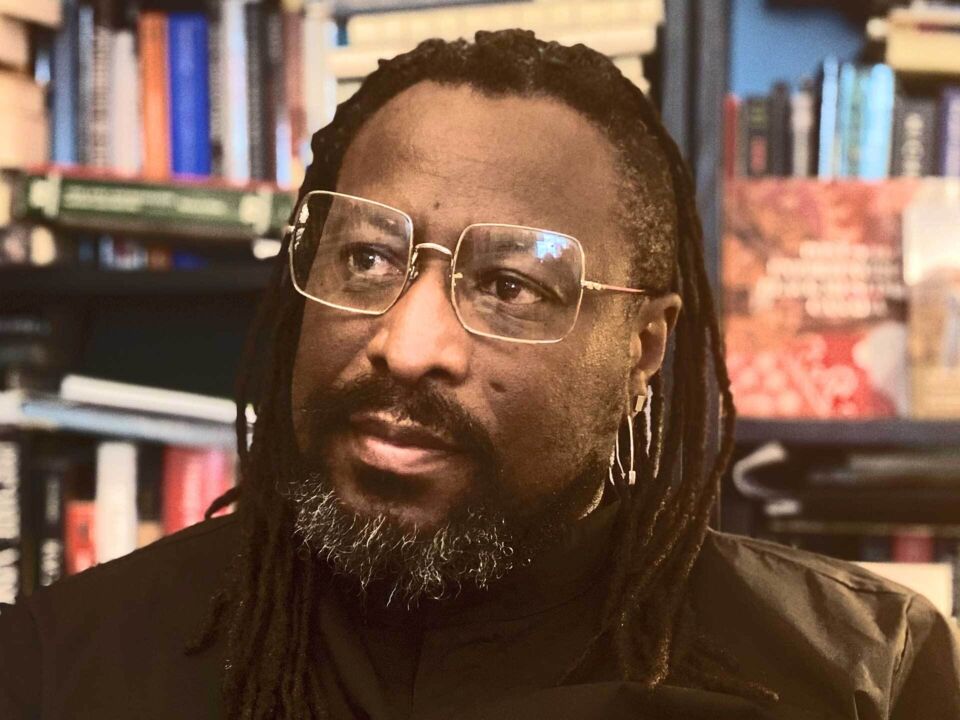

I often think about why I so enjoy hosting, cooking, and the conviviality of conversation over food and drink. I have concluded it is an inheritance of sorts from two people who have profoundly impacted my life: Erla Walcott, my mother, generous and kind to a fault; and Austin Clarke, my friend, confidant and teacher, someone whom I greatly admired. Clarke was the consummate host. He was a host whether in his home, a bar, or a restaurant. I learned a few things from him in our friendship.

I began with the menu of the recent lunch because Clarke was also at his best hosting around food and drink. The martini was his singular cocktail. His cooking was performance art—a dinner was hours in length, beginning with drinks, then plenty of talk on literature, politics, history, a little gossip, maybe some shade, and the completion of cooking that could go on for hours, well past midnight. Thinking about Clarke’s hosting could verge on the nostalgic, but remembering his kitchen manoeuvres is also a kind of legend, too.

One of my most vivid memories of Clarke is watching him walking down Shuter Street with two small reusable bags (well before it was de rigueur to carry such bags) after a shopping trip, usually to Kensington Market, but sometimes to St. Lawrence instead. In those bags would be pig tails to add flavour to rice and peas (these would be extracted before guests arrived, in case pork was prohibited for some); “West Indian sweet potato,” pear (avocado), cucumber and parsley for the leafy salad, oxtail to be stewed, salt fish for the Bajan fish cakes (always the appetizer made from salted cod), chicken for peanut chicken, other fresh herbs (especially thyme), okra (for the Cou-Cou, that Bajan take on fufu or polenta, depending on your reference point), and so on. Clarke was an expert at shopping for exactly what was needed for the meal that day. I always marvelled at how all his shopping managed to fit into those two bags and to feed all of us at dinner. But Clarke always had tricks in his culinary repertoire.

I have inherited his love for hospitality. I did not expect this to happen. I remember as a child the resentment I felt having to accompany my mother for groceries in Barbados. She made many stops on these trips: a supermarket for specific items, one lady for bananas, another lady for herbs, and yet another for ground provisions, and so on. I would be sullenly irritated. And along the way she dropped off used clothing for people she knew were in need. A shopping trip with her was a network of meetings and relations that also included visits to fabric stores for zippers, thread, buttons, and fabric, since she was a dressmaker. I endured. But sometimes my young eyes were needed to match fabric to thread or to confirm the match was the correct one. While other boys (yes, boys, it was boys) played football or cricket, I was learning where to put the pressure of my thumb on the pear (what they call an avocado in Barbados) to see if it was ripe enough for immediate use or needed to ripen some more. I resented these shopping trips. I am now so glad I got to experience them. I can move around a market or a grocery store with a determined confidence as an adult.

In Pig Tails ’n Breadfruit: The Rituals of Slave Food, Clarke returned to the scene of a certain Barbados to both channel and re-invent the Caribbean (Barbadian) cuisine of his youthful memory, while also writing about his adult life. Pig Tails ’n Breadfruit draws on history, memory, encounters, and influences from a shared past of slavery gained through migration. Clarke’s memoir of food, the historical past, and memory is as much a statement on the culinary prowess of Black diasporic invention as it is a nostalgic memoir of a time past. Slave food—that category of cuisine that is an “unspeakable thing spoken”—is furthermore consumed as a kind of terrible inheritance. In Clarke’s hands it is reverential. Part of slave food is its inherent quality of the inheritance of hospitality, of its sociality. The food is not just nourishment, but is a way of being together. It is an act grounded in what was destitution, but now becomes a form of kinship, a political community. This inheritance is then a radical refusal of subjection in favour of prolonging the ongoing memory of slavery, its afterlife, and Black survivance.

I have been deeply influenced in my thinking on hospitality by Jacques Derrida. In his long essay “Of Hospitality,” Derrida is not primarily concerned with the hospitality of entertaining, even though such a practice sits at the foundation of the assault he launches on the relation between the host, the guest, and the stranger. Derrida is much more concerned with how we might transform the relations of domination in favour of the stranger or the guest on simply being at home, but fully occupying the home. And yet, Derrida allows me to bridge a gap between Clarke and what I have called in my own work a pure decolonial project—such a project is also dependent on a different account of time. Derrida writes:

The master of the house having no more urgent concern than that of letting his joy shine out over anyone who, of an evening, will come to eat at his table and rest under his roof from the fatigues of the road, anxiously awaits on the threshold of his house the stranger he will see rising into view on the horizon like a liberator. (129, emphasis in original)

In Clarke’s practice and performance of hospitality, the breaking of time is a fleeting moment of freedom, authored by the slave food and its revised afterlife, as ingested in Canada. The hospitality of the moment instantiated a practice of momentary fugitive flight—a break within time and a strike against the Euro-American clock. For just a moment. But even more subversively, Clarke’s Pig Tails ’n Breadfruit brings Canada back into the story of slavery, back to the time of its brutal founding. It brings this nation back from a sanitized time of a multicultural state of being, exposing Canada as a nodal point in the violence and brutality that is constitutive of both its making and its place in the Euro-American modern world. Clarke’s culinary performativity is a pure decolonial hospitality in which Canada meets its history from the perspective of the slave.

I can taste the fish cakes now as the time of dinner unfolds … ingestion is political.

Bajan Fish Cakes

1.5 lbs of salted cod fish

1 small onion

3 garlic cloves

1.25 cups of flour

2 teaspoons of baking powder

1 egg

.5 cup of milk

.5 cup of water

10 oz of butter

.25 of spring onions (green onions)

Sprigs of thyme, parsley, marjoram, picked off stems and finely chopped

Black and white pepper to taste

1. Place the salt fish in a saucepan with water to cover. Bring to a boil and pour off the first set of water. Bring to a boil again in fresh water for about 30 minutes. Check saltiness of the fish. If overly salty boil again until the salt does not overpower taste.

2. Shred the salt fish with a fork or fingers.

3. Put all ingredients in a mixing bowl and mix until well combined.

4. Deep fry tablespoons of the batter shaped into balls over medium heat until golden brown and cooked through. Make sure the middle is cooked and not doughy.

5. Drain on paper towels and serve with hot sauce or a mayonnaise-based spicy sauce.

Adapted from Bajan Cooking in a Nutshell, Sally Miller, 2018, Miller Publishing Co. Ltd.

Recommended further reading:

Clarke, Austin. Pig Tails ’n Breadfruit: The Rituals of Slave Food. Vintage Canada, 2000.

Derrida, Jacques. Of Hospitality: Anne Dufourmantelle invites Jacques Derrida to respond. Trans. Rachel Bowlby. Stanford University Press, 2000.

Walcott, Rinaldo. The Long Emancipation: Moving toward Black Freedom. Duke University Press, 2021.