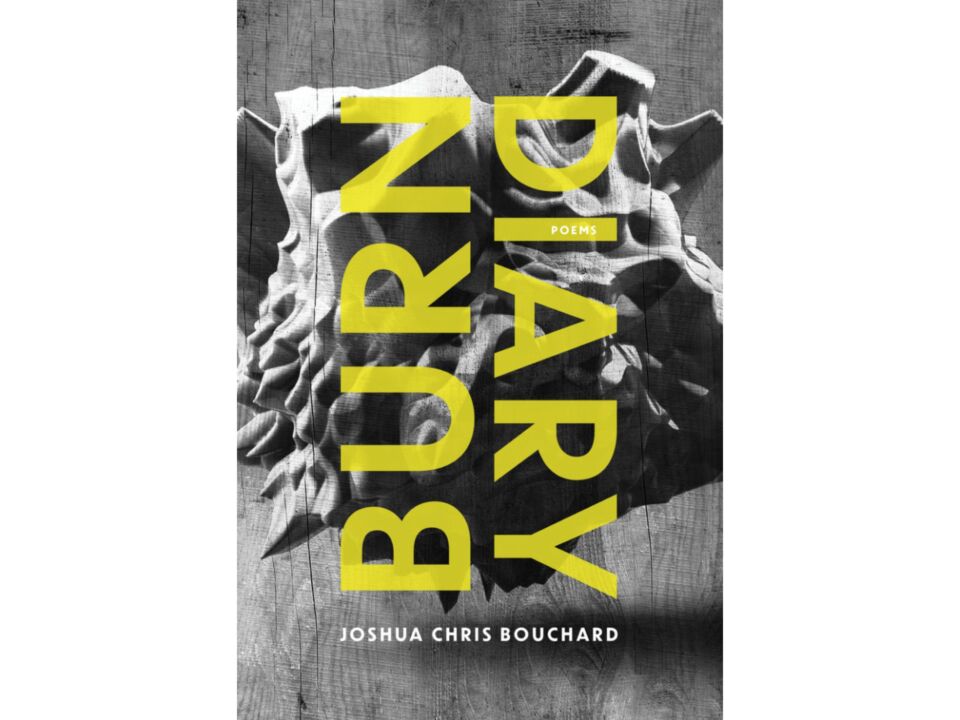

Of Grace and Cruelty: A Review of Burn Diary by Joshua Chris Bouchard

In his debut poetry collection Burn Diary, Joshua Chris Bouchard pieces together his memories of growing up in a small town in Northern Ontario. The poems explore the texture of Bouchard’s hometown—the particularities of the land, the rituals, the people—as well as the difficult feelings that come with having left the place that formed you. Burn Diary is preoccupied with the cruelty and grace of ordinary moments. It demonstrates the way in which everyday life can be remembered with intensity. However, the collection does not provide a linear narrative of Bouchard’s life. The poet’s memories exist as sharp fragments—interrupting each other, occasionally becoming surreal.

Bouchard’s poems explore the uncomfortable interplay between tenderness and violence—particularly in their representations of the natural world. In “How to Tear a Partridge Apart,” one of the few poems about hunting, the speaker looks down at the bird that he has just killed: “Put your hand on its body. Stuff it / in a plastic bag.” What could have been a gesture of sympathy or a moment of connection (touching something that is wounded) shifts to careless force—the suddenness of which feels rough in and of itself. The speaker then describes the way that he carves the body of the partridge on the command of his father. All that is left at the end is the creature’s feet which he keeps as a souvenir: “make the talons open and shut, pretend the secret thing / it came from once had life. You laugh deep in the woodshed, / sharpen knives with spit.” Sometimes children may use play to both escape and understand their circumstances. It is unclear which is happening here. However, we can see that the child is able to find delight in an otherwise gory situation. Of course, this seems to necessitate some amount of disconnection from what is actually taking place; notice how the child immediately appears to forget that the talons he is playing with were once part of something alive. This is cemented by the assertion that concludes the piece: “One day soon, you’ll hate all of this.”

In the poem “Burial,” the landscape itself is wounded as the speaker describes “[a] row of blades / above a broken knee of land,” “[chewed] sinew of hinterland,” and “[the] bruised shore / [which] keeps lakes from thawing.” The speaker projects his pain onto his geographical surroundings. This sort of imagery also captures the melancholia of small towns—the way that they can often feel sparse, isolated, and forgotten about in the national narrative. However, this same poem also imbues the landscape with a sense of familiarity. For instance, it starts and finishes with references to the paths and trails which cut through the town. While these kinds of routes may feel prescriptive, they can also allow us to navigate vast spaces. Once again, opposing sensations—pain and comfort—collide into one another.

In contrast to Bouchard’s use of injury as a metaphor, there are his accounts of real bodily injury. In “Help,” the speaker describes how a friend once lifted up their shirt and showed him their cancer scar as he worked at a Dairy Queen on a rainy day. In response, he made the friend an ice cream cone—messing up the swirl tip, he says—and gave it to them for free. It does not seem to matter that an ice cream cone is a minor gesture of sympathy; no one is keeping score. The speaker then describes himself and the friend smoking pot behind a church: “You showed me your life like almost nothing / I’ve shown you. How did you survive it all?” The monotonous—a basic ice cream cone, the grey weather, shitty weed—is the basis for intimacy in this poem, bringing comfort in the wake of crisis. While the speaker worries about an imbalance between what the two friends have experienced, it again feels like no one's keeping score. In any case, the monotony dissipates and the friend’s exit from the scene is almost sublime: “I could see it as you walked away, then sun broke, / in the clouds just above you as you disappeared / over the hill.” At times, Burn Diary suggests that violence and tenderness may be interdependent experiences, that you must feel one to feel the other. It also shows how they can be mistaken for one another. However, at its core, the poems gestures to the way in which we can feel at home in both experiences.

Burn Diary is very noticeably a text that is preoccupied with the natural world and its rhythms. This is evident from the opening poem “Miracle” which represents the speaker’s birth and how he is welcomed into his family:

... the earth pries my fists and they hold

me in their image. This is a sacred rite and now

you belong to the earth. Thank you, I now succumb

to the world.

At the very beginning, the poet emphasizes how his subjectivity is mediated by his relationship to the land. However, in quite a few of the poems, there is a particular focus on the hidden parts of the land—crevices, holes, the forest floor, the underground. In the same poem, the speaker goes on to describe his early upbringing as such: “Bootlegging lives like criminals, they teach me / where they keep faultlines at the end of dull / day” He comes of age encountering an abyss, risking falling into something dark and uncertain. Thus, “Miracle” suggests that the ground beneath our feet is not always so solid. The land is not something for the child to explore or conquer. It contains an unknowable will and demands humility.

Poems in Burn Diary gesture to the concealed worlds within our own: root underground, overlooked pockets of earth which provide shelter, the soil constantly breaking down and changing matter.

The poet moves deeper into the earth in poems like “I Think of Thought” and “Controlled Burn.” These poems, also along with many in this collection, are in the second person perspective. In the former, the speaker starts by observing the roots lying beneath the concrete. He speaks to some unknown person who seems to admire him (though he implies that this is not deserved) and who he admires as well. “You live inside / the burrows and mend them with / your movements,” he says to them,

... You ask nothing of love,

like music in the empty arenas

of your chests.

I think of you

thinking of me, how we’ll

never die.

In this poem, the burrow is a structure that is constantly made and remade. Hidden in the earth, the friend is someone who wants for nothing; love for them is not a driver of desire but rather something that they are subject to. “Controlled Burn” is a far more brutal piece as the speaker talks to a dead animal that he haphazardly cremates:

We put

you out of your gull, push

you over the roots of

red and green pines,

stoke the pit with brush

It isn’t hard to throw

you in, dissolve this

all into the soil, black

plastic under paint.

Once again we are reminded of the root systems alive just under our feet—life sustaining and hard to kill. The poem also points to the ability of soil to assimilate and transform matter, even in cases where it has been carelessly discarded. Like “I Think of Thought,” this poem also ends with an allusion to immortality:

You are calm when

engulfed in smoke …

… ash slowly replaces the air,

hands collect it like a basin.

Despite their rough treatment of the corpse, the people in this scene gather what is left of the dead animal—almost resisting its disappearance. These and other poems in Burn Diary gesture to the concealed worlds within our own: root underground, overlooked pockets of earth which provide shelter, the soil constantly breaking down and changing matter. All of these are imbued with antiquity and permanence within the poems.

The poems’ attention to these aspects calls on us to be mindful of connections in the natural world and, by extension, our social relations. How are lives dependent on one another? What is stable and what is constantly changing? Is there such a thing as a common origin? The poems also offer a particular vision of transformation. The images of the child gazing down into a fault line, the friend perpetually mending the burrow, and the soil breaking down matter speak to types of change that are gradual, repetitive, and outside of one’s control. In fact, throughout the collection there are various instances where the speaker takes on a position of passivity, describing change as something that happens to him. For instance, in one of the collection’s most somber poems “Letters to Lost Children,” which starts with the death of a good friend, the speaker reflects on his estrangement from old friends:

... I haven’t heard

from you, but I’ll wait, and I know

your sister will let me know how you are …

… When we meet, tell me stories, tell me things.

… Time moves so quickly, it’s dizzying.

All this is life.

The collection suggests that while things are constantly transforming, we often cannot force this process in any direction. There is a sense in which this outlook on transformation is dispiriting. However, I would argue that it emphasizes the value of being still and going through the motions.

While there are tonal and thematic throughlines between the poems in Burn Diary, Bouchard offers a good deal of formal variation. There are pieces that are composed of one long stanza and others that are single lines divided by large gaps. There are poems with mostly punctuated sentences and ones where the lines more often break off abruptly. Therefore, Bouchard is able to offer the reader different forms of engagement. The pieces that are more formally cohesive flow like a stream of consciousness. They wash over you; you are called upon not to dwell on any one part of a poem but rather the atmosphere that it creates in the end. Meanwhile, the poems that are more fragmented demand a more methodical and careful reading. They draw attention to each individual line and readers must spend more time piecing together meaning. The visual contrast between the poems where the lines are tighter and those where they are more separate also mirrors the collection’s preoccupation with the tension between intimacy and distance.

As discussed earlier, Burn Diary contains the first and second perspectives—sometimes even within a single poem. With some exceptions, it is often unclear who the speaker is addressing in the second person perspective. The only thing we can assume is that it is someone from his past with whom he has lost touch for some reason. On one hand, the experience of reading these pieces feels intimate. The reader feels like they are in direct dialogue with the speaker and sometimes like there is a complicity between them. At the same time, it is also alienating because we feel misrecognized; we know who we’re not the person the speaker is trying to reach. The second person perspective gestures to something left unsaid or unresolved within these relationships. The poem constitutes a space to work through memories and to aspire to a provisional resolution.

Burn Diary reconsiders the idea that coming of age is about finding your place in the world. It shows the past as not something that we can leave behind but, instead, something that constantly surfaces to both challenge and soothe us. Moreover, the poems ask us to look outside of ourselves (a difficult task in a highly atomized world) and see the natural and social systems to which we belong. The collection ends powerfully with the declaration: “Nothing I mourn will be sacred.” Bouchard calls on us to resist simple, nostalgic narratives—especially those related to our own memories—and to confront all the contradictions that we’ve lived through.