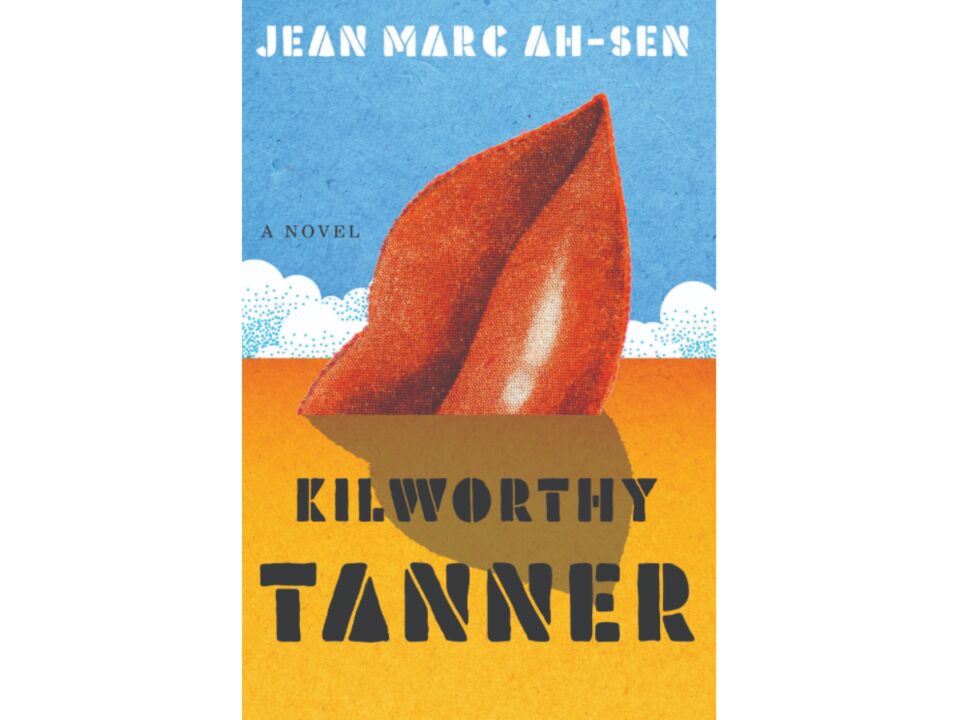

Literature as Bloodsport: A Review of Jean Marc Ah-Sen’s Kilworthy Tanner

At a time when literary feuds mostly amount to bitter tweets, Toronto author Jean Marc Ah-Sen’s latest novel, Kilworthy Tanner, crackles with hot-tempered writers brushing up against each other at events, erupting into scuffles, and devising elaborate schemes to sabotage their rivals. Authors pen thinly veiled fictions to disparage each other; brawls break out at not one, but two, stops on a reading tour that unfurls like a chaotic road comedy; drinks are splashed in faces; and in a “ritual sacrifice of glib autofiction,” copies of a foe’s new release are torn, thrown, and stabbed with a studded shoe heel at a book launch. It’s a high-octane, often-cartoonish depiction of a literary scene, but at the centre of this romp, Ah-Sen circles many truths about the competitiveness that besets the publishing world.

The book’s narrator, an aspiring writer in his early 20s named Jonno, decides to ditch Toronto’s underground music circuit after several of his bands fail to pick up steam. “I was sick of skulking around in dives,” he says, “never seeing the sun except at dawn.” The settings of his nocturnal lifestyle are given a grimy coating, like when Jonno observes that Club 56 (which, true to the novel’s starting point circa 2004, was a real basement bar on Kensington Avenue that closed that very year) has “a distinct smell of wet, overused towels casting about the room.” Drug-related slang is scattered to sketch out these spaces: ecstasy is referred to as “thizz,” a character worries if the stash was “spazzed,” while another is said to be “bugging on bottle tops.” Once Jonno reads a novel by the lauded local author Kilworthy Tanner, his childhood dream of being a writer is reignited. He encounters Kilworthy at a party not long afterward, and their relationship rapidly turns into a twisted kind of literary mentorship, laden with heavy substance use, kinked-up sex, and manipulative power dynamics.

It’s a high-octane, often-cartoonish depiction of a literary scene, but at the centre of this romp, Ah-Sen circles many truths about the competitiveness that besets the publishing world.

The book we read is revealed to be the result of Kilworthy suggesting to Jonno that he write about the development of their creative collaborations. Billed as a “pseudobiography,” Kilworthy Tanner begins with a prologue in which Jonno notes the integral role Kilworthy played in sparking his writing career, but also gestures toward the “years of very bad bloodsport and even poorer, unbecoming behaviour” that arose between them. Right off the bat, Ah-Sen’s comedic sensibility is apparent, as Jonno’s formal attempt to pay due respect to Kilworthy is peppered with references to their “co-humiliations,” their “contretemps,” and “their acrimonious separation, which spilled out into the gutters of the literary world.” There are bursts of sophisticated diction, yet the narrator refrains from taking himself too seriously as he recounts the id-driven hijinks of his milieu. In the prologue, Jonno also mentions that Kilworthy published a “burlesque of [his] genitals,” titled Drippydick, and “besmirched [his] reputation,” effectively rounding out our first impression of her lewd humour and venomous tendencies. The epigraph of the book’s first section is a quote attributed to her: “Be fruitful and vilify.”

That Ah-Sen dedicates Kilworthy Tanner to one of its characters in the front matter—as if even that was written by Jonno—shows the author’s commitment to making his stories spill beyond their pages. Links between his books can be found like Easter eggs buried within them. Ah-Sen considers his debut novel, Grand Menteur (2015), to be a “loose prequel” to In the Beggarly Style of Imitation (2020), his collection of stylistically and formally varied pieces. Beggarly Style, for instance, opens with a story that follows the daughter of a character in Grand Menteur, and its introduction is presented as being written by none other than K. Tanner herself, who explains that the collection emerged out of a literary movement called Translassitude, the name Jonno and Kilworthy give to their collaborative endeavour. An Ah-Sen completist will also notice that several of the writing projects described in Kilworthy Tanner closely resemble ones belonging to the author’s oeuvre. The first novel Jonno and Kilworthy work on together, about Mauritian street gangs, shares its subject with Grand Menteur; a chapter in one of Jonno’s books has the same title—“Swiddenworld”—as one in Beggarly Style; and Jonno spearheads an omnibus novel written by a cohort of authors, which calls to mind Disintegration in Four Parts (2021), a joint fiction project by Ah-Sen, Emily Anglin, Devon Code, and Lee Henderson. The constellation of these pieces maps out what André Forget aptly calls “the extended Ah-Sen universe” in his review of Beggarly Style, evidencing the author’s panoramic, puzzle-like approach to writing that shrewdly glides across diegetic planes.

After Kilworthy Tanner’s prologue, there are only a few metalepses when Jonno’s authorial voice intervenes in his narration of the story, jolting the reader into recalling the narrative frame: Jonno wrote this pseudobiography with the supposed intention to record his history with Kilworthy. But instead of being able to capture much about Kilworthy, his chief object of fascination, Jonno primarily depicts his own frustrated attempts to understand and stay close to her over years of opaque relations and fallouts. Kilworthy is too guarded and capricious for Jonno to give us an intimate picture of her psyche, and the time he spends pondering why she’s kept him at a distance reveals more about his own insecurities and projections.

When Jonno describes sleeping with Kilworthy for the first time, he explains to us readers that he “spare[s] no detail in this regard not out of any kind of obsessive, autobiographical fidelity,” but because he hopes to annoy one of Kilworthy’s other suitors, Lovel, who might also read the book in our hands. Though Jonno claims that he wishes for his book to be an “account-taking” that “does not trade in moral excellence,” his writing, like the writing of most authors around him, often serves as an arena for score-settling and self-vindication. For all the subtle or not-so-subtle shots fired across the battleground of the page, and the avowed striving to set a story straight, Jonno repeatedly betrays his own fallibility, the potential holes in both his moral character and account of events.

At the centre of Kilworthy Tanner is an exploration of fiction writing and how it’s shaped by social and economic forces. Shortly after Jonno and Kilworthy first meet, she starts providing him with editorial guidance, which keeps him plugging away at his writing even when his confidence wavers. They invent writing methods with strange names like “draffsacking” and “tuyèring” to fuel their collaborative process, and Jonno’s awarded something called a “Kil point” every time he comes up with a new concept. It’s hard to make complete sense of why an accomplished, austere woman like Kilworthy would engage in these games with Jonno—other than for the companionship and supervision he provides during her benders—but the Translassitude partnership allows Ah-Sen to illustrate a less individualistic, more playful, approach to literary production, one that seems to mirror his own.

Jonno reflects on how collaboration is embraced in many art forms, yet stigmatized when it comes to writing fiction:

Voices had to be distinctive, unfiltered, fiercely independent, unless someone outside of the industry needed help charting the unnavigable waters of self-delusion. In any other circumstance, pairing two or more writers together meant you applied the same disrespect to both that you normally reserved for a ghostwriter.

By raising these considerations, Ah-Sen’s novel steers clear of romanticizing two minds joining forces in pursuit of literary brilliance. After the fun of their “exploratory co-writing,” Jonno and Kilworthy reach several messy impasses where it must be decided who will get publicly credited for the work they produced. As a celebrated author with an already-carved image to maintain, Kilworthy is reluctant to publish a co-written novel, and Jonno grows resentful about her unwillingness to leverage her success to help kickstart his career. The more time he spends chasing a writing credit, the more disillusionment about the cutthroat nature of publishing sets in: “Writers never like sharing resources,” Jonno states. “Whether as a matter of pride, or contempt for anyone nipping at their heels, I couldn’t say. [ … ] Writers talked a good game about community, but whenever one of them crossed the invisible boundary between mainstream success and the underground, they never looked back to any of us left trailing in the dust.”

It also becomes increasingly clear to Jonno that class disparities dictate publishing opportunities. Once he and Kilworthy start writing and sleeping together more frequently, Jonno spends a stretch of time living in her house, a “Tudor style residence in Wychwood Park” paid for entirely by her father, who experienced substantial success as a painter and author. Despite Kilworthy’s own acclaim as a writer, her financial comfort is primarily afforded by a paternal safety net, while Jonno depends on the $750 monthly stipend she pays him to perform “various odd jobs.” As much as he wants to win Kilworthy’s barbed affection, Jonno also stays in her orbit because of the professional advancement he hopes she’ll grant him, and because being on her payroll frees up time for him to write.

One character in the book, a jester of sorts named Gash, fabricates an author persona with a haughty air of mystique around it. Word about him circulates throughout the Toronto literary scene—more for his sleazy behaviour than any remarkable talent—and people catch onto the fact that, even though he ostensibly has no shortage of money, he moonlights as a food runner. “The restaurant job was a poor attempt at relatability,” Jonno surmises. “He was like a debutante, but for unfashionable society—a reject from up on high coming down from the mountain.” (Ah-Sen excels at taking this kind of withering jab at the book’s most foolish characters. He bestows this skill upon Jonno and Kilworthy, who craft creative insults in another writing exercise they dub “sillycutting.”) Later, when Gash gets tired of his working-class cosplay, he stops hiding his wealth and becomes consumed with a new pastime: fighting the opening of a safe injection site near his home.

Finding himself in a position where he must shamelessly take advantage of whatever connections he can in order to get his work published, Jonno fumes at the thought of Gash’s charade: “I didn’t have time for principles and respectability anymore. Gash could ape those things because he had money to fall back on. He could afford inscrutable moralism.” This connection between class and moralism in literature is traced again when Jonno, in an interview, is asked what he takes to be the most pressing concern for writers working in his day. “The idea that a work only has value if it is morally instructive is outdated,” he responds. “This is how you get bourgeois writers sympathetically talking about the working class by throwing politics around like they’re returning a glass of wine at a restaurant.”

While this passage finds Ah-Sen stepping into another at-times-bothersome trend of the contemporary novel—namely the explicit inclusion of commentary about the state of the contemporary novel—it feels earned in Kilworthy Tanner, since the book satisfyingly avoids moral didacticism. The guardrails of social norms are tossed aside, and self-aggrandizing behaviour runs amok. Instead of moving toward redemption, the characters remain mired in their flaws and wrapped up in petty grievances (aside from Kilworthy’s father, Artepo, whose sporadic presence offers a warm counterweight to everyone else’s rough edges). Kilworthy is prone to making the most cutting possible remarks to the people around her, and she essentially keeps Jonno on a leash while kneecapping several of his attempts to build an independent writing career. He’s deeply devoted to her, clearly in love, but she treats their relationship like it’s of little importance. At the same time, Jonno’s outlook is clouded by misogyny and a victim complex. He’s often incapable of seeing that he recklessly plays with women to meet his own carnal ends, instead holding onto the belief that he is “just a crumb, like any other in a sea of unlikeable and unknowable crumbs.” Occupying his perspective can be unsettling at points—like when he archaically refers to women as “the fairer sex,” or mentions that he can only befriend them when he finds them unattractive. But despite this, and the possibility that Jonno’s loyalty to Kilworthy and self-sustained work ethic may earn him a fair deal of respect from the reader, the novel is compelling because of how it’s ultimately propelled by poorly behaved adults: using each other, thwarting each other, and, in surprisingly endearing ways, always ending up drawn back together.

The guardrails of social norms are tossed aside, and self-aggrandizing behaviour runs amok. Instead of moving toward redemption, the characters remain mired in their flaws and wrapped up in petty grievances.

“Tanner is one of the greatest women I have ever known on this scum-ridden offscape,” Jonno writes towards the end of the book. “She’s the whole package—vulnerability, intemperance, sagacity, pettiness, fortitude, depravity.” With its slapstick plot devices, snappy dialogue, and acerbic punk spirit, Kilworthy Tanner is instilled with that same engrossing multiplicity.