A History of A Noise

ART XVI

Permettons a tout nos sujets habitants des iles de se siasir de toutes les choses dont ils trouveront des esclaves charges, lorsqu'ils n'auront point de billets de leurs maitres ni de marques connues, our etre rendues incessamment a leurs maitres, si leur habitation est voisine du lieu ou leurs esclaves auront ete surpris en delit: sinon elles seront incessamment envoyees a l'hopital pour y etre en depot jusque'a ce que les maitres en aient ete avertis.

—Codes Noirs, King Louis XIV, 1685

What is the highest nature? Man is the highest nature... The question is this—Is man an ape or an angel? (Loud laughter.) My lord, I am on the side of the angels (laughter and cheering.)

—Benjamin Disraeli, in his speech “Church Policy,” delivered at Oxford in 1864

There are many names for what sounds she leaves behind. But she prefers she had hoped for pearls.

In year five of her leaving, she found a wound in a mountainside.

On the day before she found the mountain, she found a flood and stepped in it.

Not many people know much more than that but someone left word in a conch shell that she was a child full of song. Anytime she found a song she fell in it. Then on the day she found her parents dead she found a tree deep inside her bedroom. Climbed it. Hung her early life on its highest branch and left for another time. The conch shell said she lived in hospitals for a stretch with Catholic missionaries. The conch shell said those missionaries mashed her up in those hospitals and then she found that she didn’t love talking. Didn’t love singing anymore. She found silence. Broke open aloneness and slept in it for years. By the time she stepped out of all that, she had unearthed enough study and dedication to the soil. She packed these into ten suitcases and left on a boat.

She makes a Rorschach of every curve of land she follows. It is her fashion of filling her curios with dirt. How she binds them for her floating house. How she would say, always, “all the doors are locked but the coasts are open.”

This is her kind of wish. She only believes what the dirt has to show in its way with water. All of the samples she’s collected over the years fill her house. Her house is a floating lab. Or the lab is her home. Fourty-three thousand eight hundred and thirty hours ago, she arrived by slipping out of a hold that carried her for miles accross the sea. She comes in search of pearls this time though she can hardly remember why. Only that she knows something of a living presence. She knows by the cornfields she’d met along her way, and the many hundred steps leading up mountain from here, that any talk of pearls could be the result of a misplaced hope. Or given what somebody here knew, a foreign logic. Hers, presumably and mercifully, which is in her as something without direction.

She was once a creature on two fleshly legs. Though now it is perfectly ordinary for her to put on and remove her wooden one. Day and night she does this with an artist’s doggedness. She’d left all the three-legged and four-legged, and six and seven and eight-legged beasts behind six-dozen moons ago. Even the Sunday-school child she had been in another life can’t be persuaded into the same uneasy ways that breathing hurts when she pulls the wooden leg away from her skin leaving her marked like a watercourse. Ways that stories are carried across a perfect horizon by the ones she comes before. To her nothing is as perfect as a horizon. Not least because horizons don’t exist. Anymore. Anywhere. Anyway.

So, the after, then.

She had been told some names. Told they belonged to people in a family tree as tall as five centuries and all she could remember was the tree deep in her bedroom that she hung her old life upon and left. The tree she could trust but not the blood, red and potent as it flowed in her. She had studied every misgiving about the language of blood. She had written the names in a book she could no longer read because it had been burned along with the bed of her last and probable lover. But now she could follow the tug of chance or logic past any wet thing—even the unthreading tide, even the temple-thick clusters of lustrous pink clouds above her—the rain pouring down equal to waves deep in the Atlantic. She, at least, was unsurprised, though not unmoved, by the Slave Age euphemisms she has learned to read (for no urgent reason), on the beige, tongue-like exterior of coral stones in this ruin of mills and rum distilleries near her coast.

But now she could follow the tug of chance or logic past any wet thing—even the unthreading tide, even the temple-thick clusters of lustrous pink clouds above her—the rain pouring down equal to waves deep in the Atlantic.

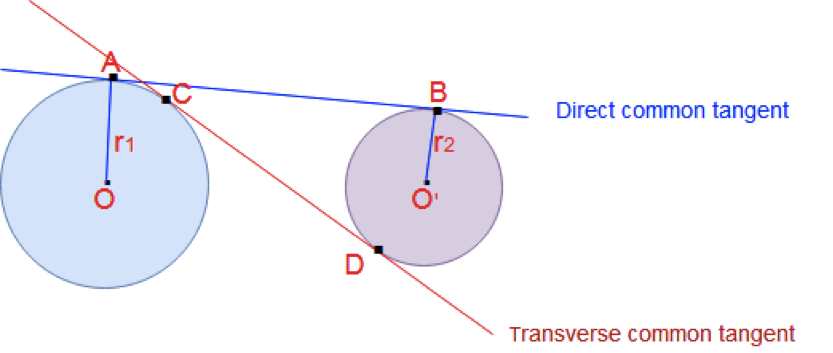

Except she now had a mountain of steps to climb. Mainly, her confidence in pearls, she thought, was something of lesser temper. Which meant she was stirred as anyone with talent for formulas, and who could reproduce them, could be stirred: P (1+r/n)^(nt) = compound interest & P = m/V (density) & Pi = 22/7 (circles) & volume (cube = a 3; rectangular prism = a b c; pyramid = 1/3 b h), etc..

She’d been raised in the wisdom that any mollusk with a shell could make pearls. Between here and Darwin, the wild remains. Miles where the wild encompass. She’d lived here alone on a sailboat since the last and probable lover. A sailboat with the usual things like sinks. An induction stove attached to a gimbal system. An oven. A desalinator and thousand-gallon water storage tank. Two wind generators and solar panels. An analog modem to allow her to send word toward a world that may not be online given the possible miscarriages of electronics. But she would know if that were to happen. She checks her storage of canned foods often for cockroaches the naked and labeled cans have kept mostly away. Beyond all this, the halfway predictable mood of the seascape suited her. Often grey and wet with longish intervals full of the playful circuitries of sunlight. Perhaps she enjoyed best that it let her move slowly through the world for some hours, unobserved.

Her assignations with friends did not come to an end when she won the grant that guaranteed her sometimeish investment in aloneness. And in the style of entropy that made her think of every night as a dim door to wonder, she did not escape their demands for her living presence. They’d call and they’d ask when might they come to her hiding place. She would say, “Come with yourselves and nothing more.” But they would come with whatever they thought should be had. A little wine, a small sculpture somebody made for her, some pumice for her peg. Hers was the sole distinguishable mission available to her in a dying world among other dying worlds.

She loves to stoop, even with the difficulty of bending at eighty-two degree angles, to remove the seaweed from the shells of large king scallop. To cover the smaller ones and conceal them so they can have half a chance to grow.

When she emerges from her study of coastlines and what the sea makes of ports, she calls her friends to arrange for some hours of thrill, for some loosening of the frequencies of careful living. Her friends would come. She had promised them, on the word of her weather monitor, that the coast would flood on the day before they were to arrive. When the coast floods and great tides deposit clams, cockles, oysters, queen and king scallops, and more interesting evidence of the sea’s secrecies, she says she feels most bright and most sedate and most odd in this place. She says she will forage. For these friends and for the sounds. She loves to hear the scallops clapping her over to them. She loves to stoop, even with the difficulty of bending at eighty-two degree angles, to remove the seaweed from the shells of large king scallop. To cover the smaller ones and conceal them so they can have half a chance to grow. She loved to fill her copper bucket anticipating friends and a cook up on the beach.

The south sea pearl oyster lives nearly four decades and its pearls can be size of a minor golf ball, she’d say to no one in particular.

But this was part of the rhythm of her living presence. Her survivancy. Her anticipation of friends.

These pearls can sell for one-point-five million dollars. In high lime, high calcium waters, a pearl can grow one-to-two millimetres per year.

True that no one but the conch shell that would tell this uneasy story twelve generations down her line was listening.

On the mountain, she paused. Momentarily thrown by the kind of opening a familiar sound makes between one point and another. The decibels of bells and chimes, a watch ticking, a rumor, something like people talking or snoring. This place, according to the most recent reliable records, was uninhabited for two hundred years. She paused. Shook perilously near a boulder. Felt her teeth loosen. She sat a moment. Finally, disoriented.

The earliest people who came here over two thousand years ago found a bay enclosed by hills. Fringed with mangrove past the marina until Bananes Bay. There were no emperors reigning from any height. Nor resigning according to some glib calendar. The bay by which they entered was rich with fish, conch, and other sea folk. They watched the coming boats. The ships parting the water. What could be understood as welcome or warning? She had read about the coastline trade that mimicked sailing together until the noises of cannons. The Harmattan dust announcing the parting wages between living and lives. Who were the architects and theorists of whatever sends her up mountain now? Were they in any comparable manner to those who brought gunpowder, mortars, and a deadly genius? She wonders at her pale reflection in a stream nine hundred feet up mountain as she drinks. She knows the cyclic composition of measurements. The subtleties of time. Candles shortening their inches via burn. Her shadow shrinking and jagged on stones and abandoned steaks. These once belonged to someone. She would have the hardscrabble late afternoon light.

She would have also the breath in her body, she reasons, as she begins to think she might do well to give up six hundred and fourteen feet from summit. One hour more. One hour she knows as invention. And now as reprieve. She has touched a new latitude. Here is a pull toward the names she is sure she can hear. Here is also the depth of the world measured against the tensing of her wooden leg.

She and her haversack had left behind her the familiar clams, birds. Ample freshwater rivering together what escaped wreckage in the meeting of La Pansée and Morne Deedon streams. She’d began her hike up Morne Tabak, first along the dirt tracks and then under the deadly shade of manchineel trees. A sharp turn north. And taking with her an even older habit of always inadvertently meeting the ground. A fall here. A fall there. A fall mid-walk. A fall pre-walk. Her depth perception, fictional at best, meant she knew nothing of what people called balance. A terrible feeling. And since it was too late for her to do anything to stop it, she met hard on the second step, landing peroneus-side, then vastus-side, her loosened peg. Cursing loudly in the direction of Saturn. The frequency of a siren. Or she imagined a throbbing rectus femoris vibrating—and lodged it in her throat. Why be alone, she wondered again, the third time that month. Why be alone with nothing but a rainbow overhead. The only thing stopping her from thinking too long again of the first Europeans, adventurers, freebooters, and pirates who found the bay, half a mile off, a safe refuge. An average thought, no doubt. Would she ever feel that raw assuredness of such men? Men who could steal permanently? Who could turn mere suggestion of refutation into a hundred years war? She thought of the now uninhabited Dead Chest, where her mother had been born, where Blue Beard marooned some of his fevered men against some rumoured threat. A bottle of rum and a sword their just equipment. Of the French who found the bay convenient for anchoring and mending their ships, in the area of the present day yacht haul-out, which is still called La Carenage. Why be alone at all.

Would she ever feel that raw assuredness of such men? Men who could steal permanently? Who could turn mere suggestion of refutation into a hundred years war?

Her peg tightened and moving with the confidence of a paramedic now, she thought, too, of the people with whom she was once a little girl, who would think all of her current occupations the culminating work foolish. And as she thought this, she looked up. Cold, thin breath filling her. The wide, liquid staging of things surrounding the mountain opened up below her.

At the summit, she could not say what had gone out in the world behind her but she felt something had. She stopped to rest and drink.

She wakes up to the core of the world, a blur. And this, slowly combusting:

We allow all our subjects, inhabitants of the islands, to be satisfied with whatever things with which a slave can be charged, when they possess no notes from their masters or known brandings, to be returned immediately to their masters, if their dwelling is near the place where their slaves will have been caught in the act: otherwise they will be sent to the hospital without delay to be stored there until the masters have been informed.

—Black Codes, King Louis XIV, 1685

And a motto: Statio Haud Malefida Carinis.

Both etched in rotting wood hung diagonal to the ground, which is golden with a metal she did not recognize—Statio Haud Malefida Carinis: A Safe Harbour for Ships.

Why this sign so far up mountain. She admires being confused. She changes her mind about the world. She does not know the world she has lived in all along. And she is relieved for that renewed breath. The strangeness makes something pure. Up there, in that part of the mountain. In that wound in its summit. She scans the space there for the names she has carried all of these years. The sounds she was convinced they must make.

Her chest shakes its five decibels. She swigs wet air and begins to pitch her tent facing west at a fast-setting sun. She reaches for her knapsack and something sudden brushes her wrist. It snags her wooden leg. She falls back. Furious and alone. She can see nothing else in the dimmed hollow of rock around her. Then a loud crash. A noise swallowed into the eighty-eight decibels of a city’s background noise. Swallowed into the ninety-seven decibels of a fire alarm. The one hundred and nine decibels of a helicopter. Swallowed by the hundred and twenty-five decibels of thunder. Then the hundred and twenty decibels of a chainsaw. The one hundred and fourty decibels of a gunshot. The one hundred and eighty-eight decibels of a blue whale complaining of a spiral. All the strange trade-offs of things the mouth of a girl makes in a world that denies her can make the air frigid, make the air wet as the sea, hot as monsoon weather. The earth quakes around her and no further. She can hear nothing else. Silence and the earth’s core heating up beneath her feet.

A wall of stone crumbles revealing an anterior wall that shone. What makes it shine is a none of her business, she thinks. In the wall is an image in amber. A ring of enslaved people near a wharf, emblazoned next to a fading expression: when the saved of the Earth shall gather over on the other shore… called up yonde… I’ll be

Another inscription, barely: freed slave soldiers in April 1796 General Abercrombie’s son levelled the town with bombs and cannon fire…

She feels her life force draining. Sweeping the trees beyond. She did not choose a life performing surgeries, or internal medicine, or other such calls to service reserved for her grandmother’s and her mother’s making. Instead she is in a mountain searching for pearls to prove something of a tree of maroons once alive or living here. This makes her smile. What made her think of pearls but the seasons no one thinks of underwater.

Location r2, here, which is her best-hypothesized picture of the place:

H.M.S. Sparrow she reads on another adjacent wall as the world starts a swirl. Liquid. Illiquid. Around her she reaches for invisible things to steady her. Her hands move slow. She thinks of her sailboat. Her pearl-less state. The rainbow she’d paused for at the foot of the mountain. Then all is darkness.

Early in the coming morning she will wake with a noise in her throat. The torrential noise of a great fish tail cutting perpendicular across the watery and troubled air between the cave—in which she is splayed on the ground and surrounded by dark, flightless beings—and a corridor of trees beyond.