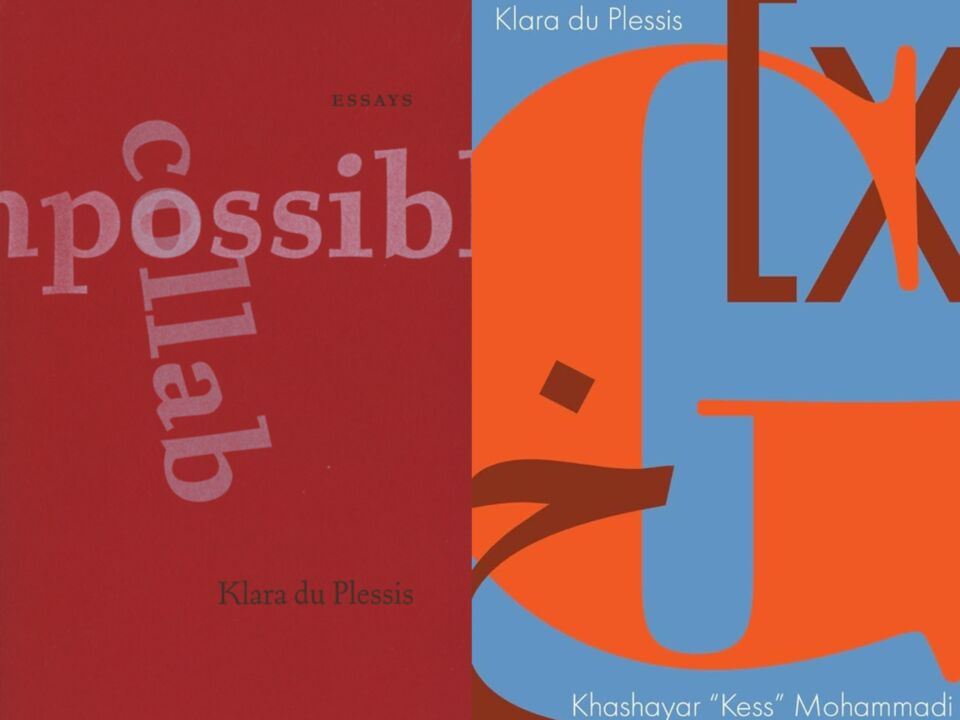

A junction of blossoming ideas: A review of I’mpossible collab and G

Collaborative poetry projects have experienced a surge in popularity recently. Hard to determine the reason for this, although I imagine the combination of the COVID pandemic and social media connectivity might have encouraged some of these forays to blossom in the crucible of enforced distance. Certain presses have also decided they’re willing to encourage such projects, particularly Palimpsest and Gordon Hill. The relatively recent release of the Acorn/bissett collaboration, I want to tell you love, no doubt also had younger poets pondering the possibilities that collaboration might offer.

Klara du Plessis has been fascinated by collaboration throughout her poetic career, although her definition of the term in relation to poetry is likely broader than one might initially think. In her introduction to I’mpossible collab she considers how writing an essay about a poet or their work is inevitably a collaborative act. In thinking through the work she is interpreting, sometimes guessing the thrust of the poet’s meaning, giving a new structure to the work necessarily shaped by her engagement with it.

In a similar manner, du Plessis’s debut book of poems, Ekke, in its way, was an exploration of how two languages shape and alter an individual. The fact of the author in essence being a “dual-language state” affects her relationship to the world at large.

Being this way inclined to pondering collaboration, it’s only natural that du Plessis is drawn to write about others who are natural collaborators. For instance, of Erin Moure she says: “Moure collaborates with herself. She collaborates with Muriel Rukeyser, Elizabeth Bishop, and Angelina Weld Grimke—suffusing her writing with their biography … ” Du Plessis notes that Moure’s book Theophylline loosens the concept of both co-authorship and the role of the author.

We are constantly in dialogue with what we’ve read, who we’ve read, and how. In her discussion of Anne Carson’s Float, du Plessis imagines the chosen form of the pamphlet-packed box as some hearkening back to Carson’s classical studies and the concept of how an object might be read.

Dialogue and collaboration is even more starkly suggested for du Plessis in Dionne Brand’s The Blue Clerk, in which left and right-hand pages converse, where the author’s work on one side of the page is being rewritten by the clerk on the other. A collaboration between artistry and raw fact.

The compact, 93-page collection of essays is thematically well-honed. Not only does it offer insight into many admired voices in Canadian poetry (Brand, Carson, and Moure, as mentioned previously, but also Jordan Abel, Lisa Robertson, Oana Avasilichioaei, and Kaie Kellough), it’s also a reminder to the practicing poet that you are never truly alone in the act of creation. Not only do you carry the library of what you’ve read, but also the multitudes that, through living and reading, you’ve become.

Probably du Plessis’s most audacious review is that of Robertson’s Boat, part way through which she acknowledges that she hasn’t actually read the book from cover to cover. Instead, she has examined elements of the book that she has read in relation to Robertson’s own oeuvre, highlighting the continuity of the work of poetic creation: “As the gap of everything diffuses itself across one line, a poem, and beyond, it creates a continuity, an ongoing aperture that replicates itself in the processual nature of the sequence. Every line read is reflected upon in the ceaseless gap of the next line and then the next.”

Du Plessis’s confession, then, isn’t so much an admission of failure; rather, it’s an admission that reading can happen disjointedly, and at every juncture ideas can blossom, laying open “the arbitrary nature of citation, how it works to substantiate a theory based on a book I had not fully read.” The essay “floats in an in-between of interpretation and self-reflexive articulation of where my mind goes as an author.” There is every likelihood du Plessis will return to Boat and have yet something new to say as the collaboration between reader and author changes but it doesn’t make this original essay any less valid.

This mutual fricative serves as a jumping off point for the two poets to explore how languages diverge and intersect. Through conversation between the two, some new understanding is created.

Du Plessis continues her exploration in the collaborative space with G, a new collection conceived of with Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi. As explained in the book, G is a sound, a guttural resonance shared between Afrikaans and Persian. This mutual fricative serves as a jumping off point for the two poets to explore how languages diverge and intersect. Through conversation between the two, some new understanding is created.

One page from the long poem “G” that serves as the centrepiece of the collection captures the essence of this engagement:

Nestle in words like an animal

mythologizing and severing

nature into morality. The antler

that gores, accidentally healing

a nail, a tooth, a horn.

The callous tip that roots into viscera

or the hoof, thickened into prosthesis.

Animal-mythos clashing

with the next door neighbour’s

worship. Language as natural mythos

agglutinated, the gorg o meesh of speech.

The italicised phrase means “twilight.” We’ve created these callouses of meaning in words, calcifying understanding in their shapes, their historical resonance. It’s a twilight of speech because it is singular. This project re-animates the porous edges of language in a very active manner, consciously meeting those boundaries.

While some sections, like the above, use metaphor to philosophize and beautify this engagement, the talent of both poets for concise delivery also shines. For example:

god is self

and

man is me

how Persian

transforms

my sense of being.

Critical to understand this is knowing “god” means “god” in Afrikaans but “self” in Persian. Meanwhile, “man” means “man” in Afrikaans and “me” in Persian. If there is one drawback to such poems, it is how the footnotes can draw you away from the poetry in the moment, but for me it just meant that each visit to a certain page of the text was different.

The poems engage with Afrikaans and Persian in this English meeting place, but at times French and German also make an appearance, suggesting a dialogue among all the languages the authors have brushed against, as if meeting beneath the Tower of Babel itself to solve the tongue’s essential need. As if to say we will inevitably meet in poetry, so let’s not shy away from exploring our limits together.

It’s rare to have a chance to read a poet’s process of thought while also enjoying the final result. As balance for this review, I would only wish to read also Mohammadi’s perspectives on the nature of poetic collaboration. As both a poet and translator (I encourage you to pick up his translation from the Farsi of Saeed Tavanaee Marvi’s The OceanDweller from Gordon Hill Press), I look forward to reading his perspectives on the topic in future.

But ultimately, that’s the statement du Plessis offers—we are always in collaboration. There is no end to the play.